By Daniel Wolff

Excerpted from How to Become an American: A History of Immigration, Assimilation, and Loneliness, by Daniel Wolff, published December 2022 by University of South Carolina Press.

Her mother had grown up during the Civil War. You could argue that her daughter, born in Minneapolis in 1886, came of age during the Labor Wars.

Part of what the Confederacy had rebelled against was the industrial future. In 1860, the nation had more slaves than factory workers. There’d been little to no industry in Charleston, St. Augustine, or Jacksonville. The role of the Southern merchant was like what it had been in the Old World: an accepted but tainted go-between. Real Southerners — real Americans? — worked the land. Or, better, owned land that others worked.

But that side, the anti-industrial side, had lost. In defeat, the family had moved to embrace the new future. Mill City created wealth through huge transportation centers and refining operations that employed thousands. During the 1880s alone, the Pillsbury Company added six mills equipped with state-of-the-art machinery. The city’s booming economy brought profit to its kings of industry and, via trickle-down, its merchants. An Alien paint store owner might be no more welcome among the city’s old established Yankees than he’d been with Charleston’s aristocracy, but at least business itself was respected. It was the lifeblood of the city and of Gilded Age America.

Industrialism brought new strains. A late 19th century study of Chicago’s Jewish ghetto, for example, concluded “it is almost impossible to maintain the old family life in the environment of the factory system, dependent as it is on the surrender of the individual to the division of labor, with its long hours and employment of women.” Her family wasn’t in the factory system and could afford to maintain a certain level of tradition, but it was different for those working the city’s milling machines, unloading goods, driving delivery wagons, painting houses. They could feel the Gilded Age turning against them. “The people,” as one Minneapolis observer wrote, “did not reap anything but disaster from the great bonanza….”

House painters might seem like hold-overs from the old handicraft economy, but mass production affected them, too. As painting became less of a skilled trade – as the family store sold more pre-mixed paints and mass-produced brushes — painters became more interchangeable, like millworkers. And with that, they lost the ability to command higher wages. The same squeeze that had caused the Great Upheaval of 1877 – and the strike of Charleston’s painters almost a decade before that — had grown more acute.

Over in St. Paul, trade unionism had taken root early, but in Minneapolis, businessmen, government officials, and law enforcement officers opposed any kind of workers’ organization. From their perspective, a union was the opposite of the American promise: an impediment to the free market, restricting who could work where and for how much. Hadn’t the nation grown great through individual achievement? Didn’t a man who owned a business (and it was almost always a man) get to determine wages, hours, safety standards? Wasn’t that what freedom meant, why people had come to this country in the first place? The leaders of Minneapolis – mostly easterners come west — prided themselves on a city where anyone could find a job, claim their place, start over. Their city, they proclaimed, was an “open shop.”

In this new civil war of workers against management (or was it a continuation of the old Civil War for free labor?), most Jewish store owners were, as one commentator put it, “bourgeois to the core…. They saw themselves as businessmen on the way up the economic and social ladder.” The owner of a paint store, for example, treated his employees decently – with a kind of Old World courtesy — and expected loyalty in return. Workers organizing, forming what they called a “brotherhood,” could only interfere with business. Owners needed the “open shop” (others called it “right to work”) to guarantee a profit that benefitted all.

But as more immigrants arrived, as the labor force ballooned, wages dropped; safety was brushed aside; job security disappeared. There was always another warm body stepping off a boat. Laws were passed to ban contractors from importing temporary workers, but tensions escalated. In 1885, when the family’s Paint and Oil House was five-years-old, Minneapolis’s painters, decorators, and wallpaper hangers decided they needed to form a local “assembly.” To organize more effectively, they joined a national organization called the Knights of Labor.

Like the Masons, the Knights began as a secret fraternal organization. At its start in 1869, the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor was more social than political: a workers club. They adopted grand titles, elaborate uniforms, private codes. A Knight recognized another Knight by wiping the right side of his (it was, at first, an all-male organization) forehead, answered by the other wiping his left side. But beneath the trappings of a secret club, the Knights emerged as a kind of national union. One of its founders spoke of the way capital “crushes the manly hopes of labor and tramples poor humanity into the dust.” After the Great Upheaval of 1877, the Knights’ growing membership demanded more concrete action from their club. It decided to go above ground. “So long as a pernicious system leaves one man at the mercy of another,” the Knights declared, “so long will labor and capital be at war.” The solution? “Abolish the wage system.”

The Knights became “the most imposing labor organization this country has ever known.” It established its own, separate assembly of women workers, though the link between workers’ rights and women’s rights was still hard for many to make. As one female organizer put it, women had “the habit of submission and acceptance;” to change that, they needed to focus on “constant agitation and education.” In 1885, the Knights won a national strike against one of the leaders of the new industrialism: robber baron Jay Gould. The brotherhood’s victory over Gould’s railroad lines helped increase membership from 71,000 in 1884 to almost 730,000 two years later, when the Minneapolis painters joined.

The local Knights’ assembly of painters, decorators, and wallpaper hangers won their action. They succeeded in increasing their pay from twenty-five to thirty cents an hour and reducing the workday from ten hours to nine. More importantly, they changed the economic status quo, with the city’s open shop suddenly susceptible to union organizing. Businessmen were horrified. As one city machinist dead-panned, “The employer was very much opposed to employees being members of the Knights of Labor.”

It was part of a national call to action, a potential rebirth of the principle of equality. As Mark Twain declared in 1886: “When all the bricklayers, and all the machinists, and all the miners, and blacksmiths, and printers, and hod-carriers, and stevedores, and housepainters, and brakemen, and engineers and factory hands, and all the shopgirls, and all the sewing machine women, and all the telegraph operators, in a word, all the myriads of toilers in whom is slumbering the reality of that thing which you call Power … when these rise, call the vast spectacle by any deluding name that will please your ear, but the fact remains that a Nation has risen.”

Twain’s list of workers left out farmers, but in Minnesota, they, too, were organizing. The wheat farmer had long believed he was being “systematically exploited by the railroads which hauled his produce, by the manufacturers who sold him necessaries, and by the bankers who granted him loans.” Around the same time the Knights of Labor began, a former Minnesota farmer and Mason was struck by how soldiers from the Union and Confederate armies had put down their differences in a Masonic lodge. He decided farmers needed an organization like that and helped charter the order of the Patrons of Husbandry, better known as the Grange.

The Grange brought isolated farmers together for education, debate, dances. As one Minnesotan described it, they gathered to hear “orators in barns, at huge picnics when whole families and villages came in buckboards, the women setting out a rich feast and singing ‘The Farmer is the Man that Feeds Us All,’ ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’…” That sense of community, of common goals, left the farmers’ families “shaking like aspens in the thunder of history.” The Grange organized co-operative buying and selling to compete against the big money interests and gave women full rights as members. By the mid 1870’s, there were 25,000 chapters across the country, involving three-quarters of a million people.

When, in the early 1880’s, the Grange decided to back off electoral politics, Minnesota’s farmers formed the Northwestern Farmers Alliance. Again, it started mostly as a social club, but in 1884, when wheat prices fell to their lowest in almost two decades, the Farmers Alliance became more political. It met with the Knights of Labor, and the two groups issued a mutual “statement of grievances and demands. Farmers and city workers weren’t natural allies: the farmers, especially Scandinavian immigrants, tended to vote Republican, while the city’s Irish immigrants backed Democrats. They were brought together by a coalition builder, Ignatius Donnelly.

Donnelly had emerged from his boomtown real estate fiasco as a self-employed author, lecturer, and populist politician referred to as the “Sage of Nininger.” An anti-slavery Republican, he’d written letters to newspaper editors arguing that “any German who came to America in the spirit of the Revolution of 1848 should certainly understand that slavery was immoral.” After the Civil War, he lobbied for reconciliation: “We should cease to regard the South as a foreign country inhabited by our enemies.” He saw a new post-war America that would either unite, or fall into the evils of corporate industrialism. Donnelly’s novel, Caesar’s Column, depicted the distant year of 1988, when New York was an out-of-control financial center and the nation was run by a corporate oligarchy challenged by desperate workers. Speaking at a Farmers Alliance rally in Minneapolis, he proclaimed, “There are really but two parties in this state today — the people and their plunderers.”

Donnelly became a key liaison between the Farmers Alliance and the Knights. He helped to hammer out shared demands for reform: to regulate railroads, to ban child labor, to establish industrial safety standards. He saw both traditional Democrats and Republicans as “plunderers” and became state leader of a third party, the Anti-Monopolists. “Wherever amid the fullness of the earth a human stomach goes empty,” he thundered, “or a human brain remains darkened in ignorance, there is wrong and crime and fraud somewhere.” He lobbied against big business and for a more democratic government where “the state was supreme over all corporations.” Donnelly believed Minnesota would be the proving ground for this alternative vision of American equality.

The two established political parties responded by boxing the Alliance/Knights coalition out of the 1886 gubernatorial race. The Democrats simply dismissed its demands. The Republicans wrote them into their platform, but their nominee for governor made it clear that he supported big business. Still, when the votes were counted, the majority of Minnesota’s newly elected legislators were Farmer/Labor candidates. While that didn’t end the wage system, or wrest all power from the old guard, it served notice that change had begun.

“Open shop” supporters fought to maintain control. They broke the painters’ union, for one, and wages were frozen or cut. By the spring of 1890, one report estimated “probably four or five hundred painters in Minneapolis; they work nine hours and wages range from 15 to 25 cents per hour.” The reason the union hadn’t achieved more? “[The trade] literally swarms with unskilled men [so caught] in the blind, senseless competition for work, cheapness has almost become the prevalent rule.”

The threat of immigrants, of unskilled “lawless hordes,” was used to squelch organizing. When an 1886 labor rally in Chicago’s Haymarket Square ended with bomb-throwing and eight dead, business interests blamed “the communistic and revolutionary races” over-running “the master races.” True Americans, it was declared – patriotic Americans – believed in a “Christian and industrial civilization which embodies all that history has achieved” and saw “guarding vested rights as sacred.” Progress itself was Christian; it was entwined with industrialism; what it had achieved should be considered sacrosanct. As each wave of immigrants arrived, “the law had to be confirmed anew against the lawlessness inherent in all uprooted people.”

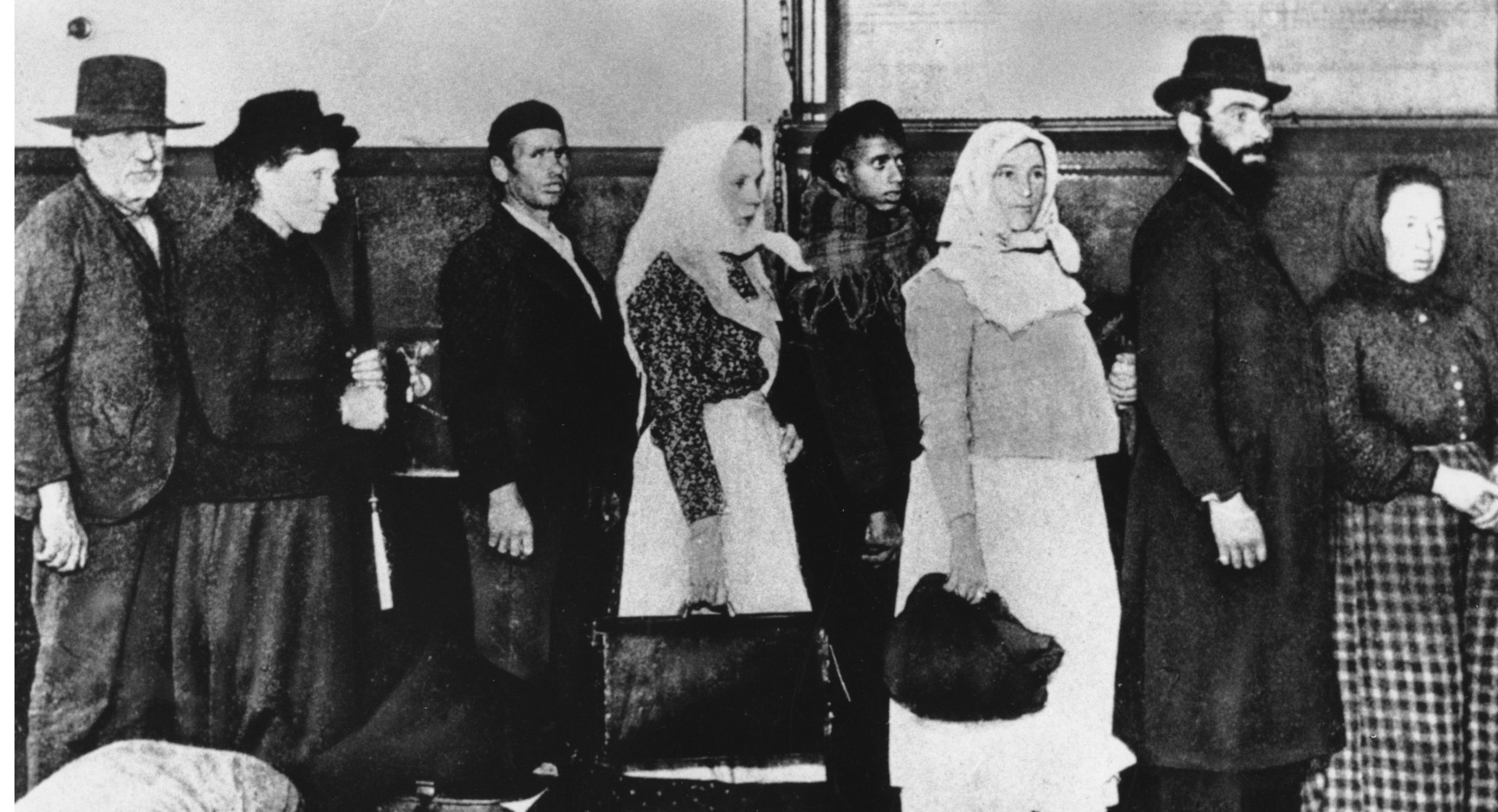

In 1891, the federal government established a Bureau of Immigration to oversee the new Aliens: Eastern European Jews, Southern European Italians, Poles. But the Bureau was also empowered to monitor the 16 million foreigners who had come to consider themselves Americans simply because they lived here. In the heightened tensions of the Labor Wars, people began to question if that was enough.

The painters of Minneapolis tried again. They joined a new union, the International Brotherhood of Painters and Decorators, founded in 1887. In 1890, having enlisted “almost every journeyman in the city,” they composed a letter to the city’s “master painters:” the crew bosses who did the hiring and bought supplies from store’s like her family’s. “We believe that a large majority of the boss painters in this city are disgusted with the way they are compelled to do work and the cheap grade of material they have to use, as well as the small wages they have to pay, on account of the low price they get for their work. How is it that in all the cities of the East they do far better work, use good materials and pay better wages and the bosses make more money than they do here? We claim that it is done through organization.”

It was an attempt to convince crew bosses that their interests lay with their crew, not big business. Joining with workers in a single unit would mean more profit for all: better pay, better materials, bigger budgets. It was like Charleston’s post-Civil War painters’ strike trying to get black and white workers to overlook their differences for common concerns.

In theory, the plea to the crew bosses could also apply to a paint store owner. It was a call to take sides, to band together against corporate control, and a Mom-and-Pop storeowner might join the union side. Wasn’t that, after all, how the store had been built? From the original immigrant in Charleston through the various brothers and sisters and cousins, they’d established a network of shared connections. The International Brotherhood of Painters and Decorators was proposing something similar: a union that functioned like a big family. “Why can we not work together in harmony for the good of our trade?” In theory, the harmony could include the workers, the crew bosses, even the store owners: the people against the plunderers.

“[T]he fruits of the toils of millions,” Ignatius Donnelly proclaimed, “are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few….” The painters’ union and others like it were trying to reverse that. But what would happen to a small business if organized labor became a reality and succeeded in having a say in, or even abolishing, the wage system? For a family that owned a paint store — “bourgeois to the core” — moving towards economic equality seemed to threaten their “sacred vested rights” as Americans.

If Americans were, indeed, what they’d become.

As these issues swirled outside, safely within the walls of their home, their daughter learned to crawl, walk, speak.

Daniel Wolff’s most recent book is More Poems About Money (Four Way Books). His poetry has appeared in The Paris Review, American Poetry Review, and Raritan, among others. Great Circle Earthworks is part of a longer series about the Moundbuilders/Hopewell culture.