Flying squirrels glow pink under a blacklight. How many other mammals do this? What causes them to glow? The hardest question of all might never be answered: why?

By Patrick Shea

The following story is adapted from an episode of Points North, a narrative podcast about the land, water, and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. Listen to more episodes at pointsnorthpodcast.org.

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: There’s this little tree frog in South America. To the naked eye, it looks yellow with tiny, red spots. But under an ultraviolet blacklight, it glows bright green. That glow is called biofluorescence. The frog absorbs sunlight and puts it back out as a different color. It’s a pretty common trait in ocean invertebrates, insects, fish; it’s even been observed in some birds. But in 2017, scientists in Argentina announced the first known biofluorescent amphibian: this polka-dot tree frog. And more than 5,000 miles away, that caught Jon Martin’s attention.

JON MARTIN: I’m sitting there like, that is really neat. You know, as a child of the 70’s, blacklight posters, and we used to have roller rinks that had blacklights. Like, who doesn’t like blacklights, right?

WANSCHURA: Jon is a forestry professor at Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin. And when he read that study from Argentina, he immediately thought of another frog in his neck of the woods.

MARTIN: An interesting thing with this tree frog – Hyla versicolor, the gray tree frog – it has beautiful bands of yellow on its underside. And I’m thinking to myself, ‘I betcha anything that thing fluoresces. This would be a cool project to do with students at Northland.’

WANSCHURA: So he orders a handheld blacklight – nothing fancy, just 20 bucks on Amazon. He catches a tree frog, cups his palm around it, clicks on the blacklight and … nothing.

MARTIN: It just looks like a slightly purple blacklighted frog. You know, nothing really glowing. Like, ‘oh, all right, well, so much for that.’ But what does one do when one has a black light, and they live in the woods? Shine it on everything; especially when you’re trying to get out of nightly chores. ‘Honey, will you take the compost out?’ ‘Sure.’ Go disappear for an hour wandering around the woods with a blacklight. So, fluorescence is in a lot of the proteins that are around us. And there’s a bunch of lichen species and fungi out there that do this. And it’s fascinating to see the world. Just green foliage with a black light turns blood red when it’s healthy, you know? And it was at one of those nights where I hear that high pitched chirp in the woods. And I’m standing right next to my bird feeder and the flying squirrels were notorious at raiding my bird feeder at night. And I just instinctively shine the light on it, and a flash of pink just goes off into the trees.

WANSCHURA: This is Points North: A podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura. What Jon saw was one of the first known biofluorescent mammals: the southern flying squirrel. It kickstarted years of ongoing research. How many other mammals have this hidden glow? What causes fur to light up pink? And the hardest question of all is one that might never be answered. Patrick Shea has this story: ‘Glowing Squirrels and the Search for ‘Why.’”

Jon Martin’s backyard discovery led to years of ongoing research into biofluorescence in mammals. (Photo by J. Martin, Northland College.)

PATRICK SHEA, BYLINE: So, a flying squirrel glows pink under a blacklight. Who cares? It’s not like you’ll see this on a walk in the woods. Well, while we can’t see ultraviolet light, some species can. Maybe blacklights can reveal an invisible world – like decoding a secret language. How are flying squirrels using their hidden glow, or are they as oblivious to it as we used to be? These are questions Jon Martin had that night by his birdfeeder. So he popped into a wildlife ecology lab to share the news.

ALLIE KOHLER: John Martin came into the room and said, ‘You guys, I just saw a bright pink flying squirrel glow in the dark in my backyard.’ And we’re just like, ‘Wait, what? Like really? What are you talking about?’

SHEA: Allie Kohler is finishing her PhD in Ecology at Colorado State University. But at the time, she was a student at Northland College.

KOHLER: And everybody was very reluctant to believe him because we were the wildlife experts in the room, and he was just the forestry guy. So what would he know about pink flying squirrels? But we all were super curious and were wondering what he was talking about and took the initiative to go and investigate this on our own.

SHEA: Allie and another student headed over to her home state to visit the Minnesota Science Museum. They went to the basement of the building to check out a collection of flying squirrels. And, of course, they brought a blacklight.

KOHLER: I think it was like the “Night at the Museum,” when you walk in, and there’s just rows and rows of shelves and drawers all organized by different species … And there’s dinosaurs on one side of the room and birds and mammals – just everything you could imagine.

SHEA: They made their way to the flying squirrel drawer. There were about 200 squirrels inside. Allie got the blacklight ready.

KOHLER: We were so excited in the beginning that we shined the blacklight when the lights were on, and we could see that pink fluorescence even in that setting – when it was just like normal lighting conditions. And we thought that was cool, but then we turned the lights off. And it basically illuminated the whole room. Or the whole portion of the room; it was just so bright. The UV light revealed this hidden fluorescent pigment in the squirrel’s fur creating this absolutely stunning neon pink effect that’s [incomparable] to any other color that’s out there. I don’t think we have vocabulary for it other than fluorescent, glow-in-the-dark, super bright, vibrant, rage, neon, rave light.

SHEA: Allie had three main questions. Do flying squirrels glow? How do they glow? And the hardest question of all: Why? That night at the museum, Allie answered the first one. Yes. North American flying squirrels glow. Every single specimen in that museum – and they came from all over the continent. So this wasn’t just one bizarre instance in Jon Martin’s backyard. This was a species-wide phenomenon. The next question was “how?”

KOHLER: It’s a lot of different things that are in the fur to make it glow. And a few of them were unidentified compounds that we don’t even know what they were. But a lot of them were different kinds of porphyrins.

SHEA: Porphyrins are a class of pigments whose molecules contain a flat ring of four linked heterocyclic groups. And that doesn’t mean anything to me, either. Translation: they’re naturally occurring organic compounds that glow. Flying squirrels have a bunch of porphyrins on their belly, and on those weird skin flaps that help them glide from tree to tree. So basically, if you could see ultraviolet light, these critters would flash bright pink every time they fly. So the “how” is – at least partly – known.

Porphyrins are the organic compounds responsible for the flying squirrel’s bright pink flow. (Photo by Allie Kohler.)

But that still leaves Allie with the big question. Why do they do this? She has four main ideas. Her first one: maybe it has to do with avoiding predators by imitating them. For example, owls also have a bit of fluorescence in their wings. And an owl will eat a flying squirrel – if it can catch one.

KOHLER: That food chain connection was really interesting for us. Because if an owl comes in and then the squirrel flashes the underside bright pink, just like the owls, it might take them a moment of hesitation to go, ‘Oh wait, are you really an owl too?’ And that moment of hesitation could be all that squirrel needs to escape.

SHEA: Mimicking a predator: maybe that’s why they glow. Allie has another idea, too. Maybe the rave lights are just sexy.

KOHLER: Yeah, there have been several studies in ecology that look at different species that use this trait for showing off to mates. So we think that in some cases the fluorescence can be used as an indicator of maybe health, where more vibrant fluorescence indicates that they have access to more resources.

SHEA: So maybe the pink glow helps a flying squirrel escape from predators. Or maybe it helps them find a mate. Those are just a couple of the possibilities Allie points to in a study published in 2019.

Four years later, the “why” is still unknown, but the research caught a lot of attention.

KOHLER: All of the publicity and media that came with it was really crazy for me as an undergrad to be interviewed by Netflix, and National Geographic and New York Times.

SHEA: And now Points North, so that’s the biggest one, right?

KOHLER: Of course. I can say that this project totally led me to where I am today. Everyone on the team, they were just so generous to allow me to be the lead author. And it was just really such a collaborative team effort, and it wouldn’t be what it was if it wasn’t for each of our roles in developing that.

SHEA: Jon Martin – the guy who saw a glowing squirrel by his birdfeeder – was a part of that team effort. And he was even featured on Welcome To Earth, a nature series on Disney Plus, hosted by Will Smith.

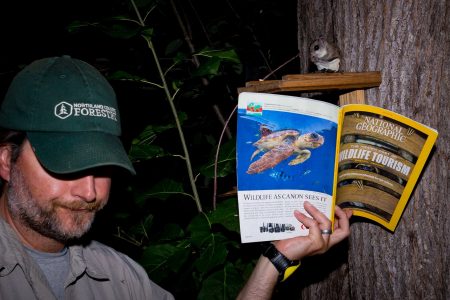

Forestry Professor Jon Martin lets a flying squirrel know: its hidden glow made it into National Geographic. (Photo by Jon Martin.)

“Welcome to Earth” clip

MARTIN: I heard something. They’re right down here.

WILL SMITH: Who knew that animals were putting on a secret lightshow in our own backyards, using colors that we can’t see? Amazing.

SHEA: I want to get into the narrative that it sounds like you’ve been asked about a lot – including by pre-slap Will Smith, by the way.

MARTIN: *laughs* Yes…

SHEA: Before his backyard discovery, Jon’s research didn’t really dabble in wildlife.

MARTIN: You know, I’ve spent my career working in forests to try and understand how they work. How trees grow, how they store carbon, how the environment impacts it. I write papers – I’ve got dozens of them, beautiful graphs, really interesting findings – nobody really knows about that work. But I happen to stumble onto a pink squirrel, and it hits the national news.

SHEA: Now that Jon happens to be the pink squirrel guy, the main question people ask is ‘why.’ We talked through some of the same possibilities Allie pointed out: avoiding predators, or finding a mate. But Jon threw out another – maybe less exciting – idea, too.

MARTIN: It’s entirely possible it’s just a thing. And that’s kind of – I mean it’s part of science. And there’s a lot of stuff that fluoresces out there that just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, right? Human teeth fluoresce. Is – does that help us? The fox squirrel famously has fluorescent proteins in its skeleton. Is there a lot of skeleton-showing off of fox squirrels when they’re mating or fighting over territories? No, you wouldn’t see this until you completely deflesh the fox squirrel and, yeah, the flying squirrel just may be a goofy thing.

SHEA: There are others, still, who say that ‘why’ might be the wrong question altogether.

THOMAS SEAGER: Science is very good at asking ‘what’ questions. ‘What happened?’ ‘What does it look like?’ How to describe it. It’s very good at asking ‘how’ questions. ‘What are the mechanisms by which these things have come to pass in the world?’

SHEA: Thomas Seager is a professor in the school of sustainable engineering at Arizona State University. That’s a very different field to squirrel studies, but he helps doctoral students prepare for their research. And he thinks a lot about the right questions to ask.

SEAGER: At the core, science can’t answer ‘why.’ So you could say, ‘Why does the tree lose its leaves in the fall?’ And then the forest ecologist might say, ‘Well, you must understand, at these temperate latitudes there’s less sun during the winter, and so it’s not economical for the tree to photosynthesize. And so it draws the nutrients out of the leaves and back into the tree, and then it allows the leaves to fall onto the floor.’ And all of that is a ‘how’ question. It says nothing about, ‘Why do we have trees?’ You could say, ‘Trees are an act of God.’ And I’m not going to question you. You could say ‘Well, trees are just a random sort of rearrangement of nucleic acids that result in some other kind of–’ and I’m not going to question you. I’m much more interested in, ‘How do the trees interact with one another, and all the other creatures of the forest?’ I don’t dare touch the ‘why’ questions.

SHEA: Thomas says the problem with asking a ‘why’ question is that it might cause a scientist to try and prove their hypothesis right instead of proving it wrong.

SEAGER: Science can only prove what is false, and what has yet to be proven false. This is a humility. This is sort of a humble approach that we take to science. It changes the way that we organize the experiment, it changes the way we interpret the data, and it goes against our human nature.

SHEA: Human nature. That’s where Thomas says the ‘why’ questions come from. He says we’re reason-seeking creatures. That’s why ‘why’ is usually the way a child frames a question about the world.

SEAGER: So, when my son was in second grade, it was the fall. We were living in New Hampshire, and we were waiting at the end of the driveway for the school bus. Cars are going by. And my son asks me, ‘Dad, why do the leaves follow the car when it goes by?’ And I’m like ‘Oh my gosh, what a difficult question. What am I going to explain, like, fluid mechanics and turbulence? This bus can’t get here fast enough.’ Mercifully, the school bus came, I put him on there, and then I had to go back and think through what we were observing – what he was noticing. I was very proud of him.

SHEA: For Thomas, it’s important for scientists to get the wording of a question right. But even so, he says the sense of wonder his son had in that moment – that’s at the heart of the scientific process. And Jon Martin says his glowing squirrel discovery is a prime example of that.

MARTIN: You know, this could have been a 12 year old kid doing this. This could have been a retiree playing around with stuff. It’s a story of curiosity, and that’s what drives the science.

SHEA: So, what’s next for team glowing squirrel? Paula Spaeth Anich is another Northland professor on that research team. She’s gone to more museums and looked at even more species under a blacklight. Turns out, this fluorescence happens in certain mammals all over the globe. The springhare in South Africa, and the Australian platypus – they both glow too. As if the platypus wasn’t weird enough already.

After the flying squirrel discovery, researchers found other mammals that glow under ultraviolet light, including the platypus. ( J. Martin, Northland College; from Anich et al. 2020, Mammalia.)

PAULA SPAETH ANICH: I think it suggests – although more research is needed – it suggests that the trait fluorescence might have been present in the most recent common ancestor of all mammals.

SHEA: Paula is an evolutionary biologist. So, she’s thinking big-picture here.

SPAETH ANICH: I always think that the evolution of mammals is just fascinating. You know, and in part because we’re mammals too and understanding mammalian evolutionary history tells us a little bit more about our own history as a species.

SHEA: If someone were to ask you, ‘Why do flying squirrels glow?’ What would your response to that person be?

SPAETH ANICH: ‘I don’t know yet, but I really want to find out.’ I mean, science helps us observe the world and create hypotheses and test hypotheses about how things function, and when things function, and what has happened. But why – I agree. I think we are using our scientific methods to try to understand the ‘why,’ but I think the ‘why’ will remain elusive.

SHEA: Whether or not ‘why’ is the right question, it’s one we’ll keep asking. It’s what we do.

For more stories from around the Great Lakes, listen and subscribe to Points North wherever you find podcasts. Apple | Spotify