By Bill McGraw

In 1968, the students returning to my suburban Detroit Catholic high school, Bishop Gallagher, had a surprise waiting for them: For the back-to-school dance that September, someone had booked the MC5, just as the band was starting to break out nationally as one of loudest and most outrageous acts of that tumultuous era.

There was a lot of good music in Detroit in those days, starting with Motown, Aretha Franklin, and Bob Seger, and hundreds of garage bands playing British Invasion covers. But the MC5 – originally the Motor City Five – were the only group promoting a 10-point revolutionary program that included a call for “total assault on the culture by any means necessary, rock’n’roll, dope and fucking in the streets.”

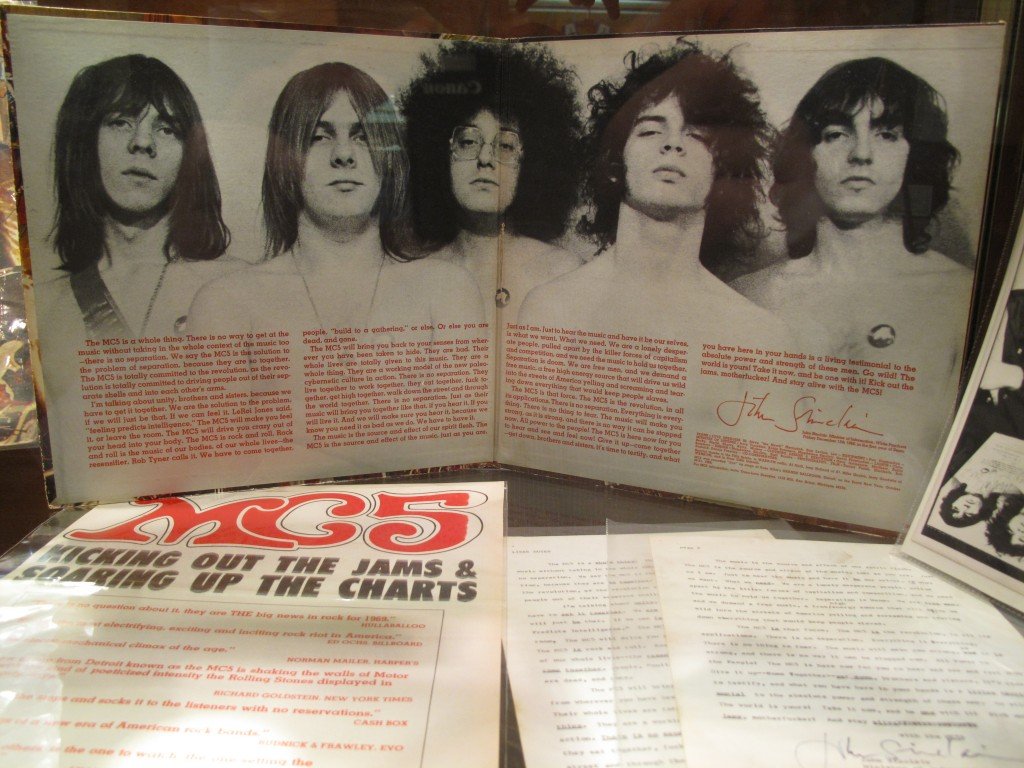

A display case of MC5 paraphernalia from The Lincoln Park Historical Society and Museum. [credit: Bill McGraw]

Four months after playing in the Bishop Gallagher High School gymnasium, the MC5 were featured on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine, and musicologists today are generally praiseful, with some considering them the first punk band, or at least an important link between rock and punk and/or heavy metal. In a used record store in Amsterdam 20 years ago, I saw a copy of an MC5 album that cost the equivalent of about $150. And it was not in good condition.

I was reminded of the MC5’s place in Detroit’s cultural history recently when I visited a small but engaging local museum in Lincoln Park, a working-class suburb in the Downriver area southwest of Detroit.

The museum’s permanent collection features displays on china tableware, old telephones, and Native Americans who lived in the area 300 years ago.

A scene from The Lincoln Park Historical Society and Museum, with Rob Tyner’s outfit the dominant item in the display case. The china exhibit is to the right. [credit: Bill McGraw]

The Lincoln Park Historical Society and Museum organized the exhibit (which runs through Labor Day) because the band came together about 50 years ago in Lincoln Park, where four of the five members grew up. In the 1960s Lincoln Park was a prime example of working-class affluence. Residents worked in the surrounding factories for union wages that allowed them to buy boats and cottages and music lessons for the children. Today, most of those factories are gone, and the city, overwhelmed by financial problems, is run by an emergency manager appointed by the governor. The shopping center on Dix Road has an outlet where you can sell your plasma.

Even at its peak, though, Lincoln Park was a sleepy bedroom community, so Lincoln Park exporting the MC5 would have been like the ultra-square Lawrence Welk show producing Mick Jagger.

The MC5’s signature song, “Kick Out the Jams,” begins with lead singer Rob Tyner screaming, “KICK OUT THE JAMS, MOTHERFUCKERS!” as the band launches into a ferocious wall of sound. An anthem to sexy, druggy, hot-and-steamy rock and roll, the lyrics run, in part:

“Well I feel pretty good

And I guess that I could get crazy now baby

Cause we all got in tune

And when the dressing room got hazy now baby“I know how you want it child

Hot, quick and tight

The girls can’t stand it

When you’re doin’ it right

Let me up on the stand

And let me kick out the jam

Yes, kick out the jams

I want to kick ’em out! “

The language, coupled with the band’s politics, its habit of partial onstage nudity, its penchant for toying with the American flag, and well-publicized fights with record labels and hassles with police helped the MC5 develop a passionate following among young people across southeast Michigan, and contributed to building a vibrant counterculture in Detroit and Ann Arbor.

Taking in the exhibit and thinking about the band’s antics made me wonder how the MC5 ever had come to sleepy Bishop Gallagher.

If Lincoln Park was an unlikely spawning ground for the MC5, then Bishop Gallagher High was one of the last places you would expect to see a band that encouraged what the Catholics, lowering their voices, called premarital sex.

Located one block beyond Detroit’s eastern city limits in Harper Woods, a working-class and middle-class suburb not unlike Lincoln Park, Bishop Gallagher in 1968 had 1,200 boys and girls who wore uniforms and were taught by nuns, lay teachers, and Christian Brothers.

The staff included progressive and challenging instructors, but the overall vibe was more Inquisition than free inquiry. A cadre of male teachers and brothers dealt with unruly boys with physical punishment that in the real world would have been classified as felonious assault. Under “philosophy,” the student handbook said: “Since God has revealed Himself to us in the person of His only begotten Son, Who alone is the Way, the Truth, and the Life, there can be no ideally perfect education which is not Christian education.”

I looked up the senior class president, Dennis Gainer, a cerebral, friendly, and adventurous classmate who is now living in Virginia. I recalled him having something to do with the MC5.

“I booked them,” he said.

Backstage with MC5 on the night they played Bishop Gallagher. Left to right – J.C. Crawford, the band’s spiritual adviser and announcer; Dennis Gainer, senior class president; and an unidentified guest. [courtesy of Dennis Gainer]

Bands usually were such a noncontroversial issue that teachers and school administrators didn’t pay much attention to the process.

“I had the idea and, somehow, they signed off on it,” Gainer told me. “But they didn’t know what they signed off on. Getting them to perform was a way to introduce some culture – counterculture – to the school. I remember thinking it was a coup and looked forward to the reaction of the faculty. I wasn’t disappointed.”

Gradually, as the Friday night of the dance approached, the adults grew aware that the revolution was about to arrive with a bang in their gym. It had been a turbulent year, with the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., among many other jarring events, and Detroit had just gone through a tense summer, the first hot months after the disastrous 1967 riot.

Less than a month before the Gallagher show, the MC5 had been the only band to show up for a wild rally near the site of the raucous Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and they escaped just as club-wielding cops waded into the crowd. Author Norman Mailer, covering the convention for Esquire magazine and a book, later described the MC5’s music as “the holocaust of decibels,” “the sound of death by explosion” and “the roar of the beast in all nihilism.”

By the day of the dance, students were abuzz, looking forward to the music and wondering if one of the band members would say “motherfuckers” or take off his pants in the blessed halls of Bishop Gallagher. The parents of a friend asked me if it were true that the band burned American flags.

As the excitement grew, pressure grew on Denny Gainer. School officials asked questions and warned him about the consequences of the band’s bad behavior. He feared they might expel him. His parents, aunts, and uncles were in the building, serving as chaperones.

[blocktext align=”right”]”I’ve been to the Grande Ballroom, I like your music, but please don’t say ‘motherfucker.'”[/blocktext]I was shitting bricks,” he recalled on the phone. “There were rumors that the Harper Woods police were in the parking lot. I was trying to be cool – I was wearing my wire-rim glasses and pendant, and I went to talk to the band.”

The MC5 used the cafeteria as a dressing room. Gainer had booked the band through an agent, and had not met the members.

“They were all smoking joints before the show,” he remembered. “Girls, maybe groupies, were coming through the narrow windows, and they were wearing coats, and some of them had no clothes underneath.

“It was the first time I had seen a woman naked. I thought, ‘Oh, God! I’ll be in jail before the end of this night. I tried to convince them – I said, ’I’ve been to the Grande Ballroom, I like your music, but please don’t say ‘motherfucker.’”

Gainer said the band members were noncommittal. “Well, man,” they replied, “we won’t know what we’ll do until we’re out there.”

The opening act was a band called the Frut, also known as Frut of the Loom. With all the concern focused on the MC5, nobody, it appeared, had checked the Frut’s repertoire. They played a song called “Blow Me.”When it came time for the MC5, J.C. Crawford took the stage to warm up the crowd. He was the band’s so-called spiritual advisor and announcer, and his usual shtick, shouted like a carnival barker and at very high volume, went like this:

“Brothers and sisters, I want to see a sea of hands! I want everybody to kick up some noise! I want to hear some revolution out there! … Brothers and sisters, the time has come for each and every one of you to decide whether you are going to be the problem or you are going to be the solution… Brothers, it’s time to testify! … Are you ready to testify? I give you a testimonial – the MC5!”

The first set was loud but uneventful, and the MC5 took a break. Tension mounted. The band returned. Tyner went last, and he ran toward the microphone. The students and adults stared at the stage. Tyner waited. And waited. Finally, he screamed.

“KICK OUT THE JAMS, MOTHER SUPERIOR!”

The audience laughed. The tension lifted. Wild dancing broke out.

The show continued without incident until school officials decided it was time to call it a night. During a long MC5 improvisation – no one is sure which song they were playing – one of the brothers told them to stop. Gainer waved his hands, trying to get Tyner’s attention above the electrified screeches. The band played on. Someone turned on the lights. One of the adults pulled the band’s power. My friend Larry Francis says he still remembers the pick of one guitarist scraping across the unamplified strings of his guitar. Tyner kept singing.

The ending, though, was anticlimatic. The MC5 had come to Bishop Gallagher High School and told “mother superior” to “kick out the jams.” Everyone, except some grumpy Christian Brothers, seemed happy. Especially Denny Gainer.

“I had a huge feeling of relief,” he said. “I thought they did it just for me.”

___

Detroit native Bill McGraw is a staff writer for Bridge Magazine in Detroit. He was a reporter, sportswriter, editor, columnist and Canada correspondent during a 32-year career at the Detroit Free Press, and his writing also has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Toronto Globe and Mail, National Geographic, Newsweek and the London-based History Workshop Journal.

Belt is a reader-supported publication — become a member, renew your membership, or purchase a book from our store.

I love that story. I’m a BG graduate. Rock on!

What a great, fun essay!

I was there that night and can confirm that everything happened as Bill has written. The tension in the room waiting for “Kick out the Jams” was almost too much for us students to bear, knowing the phrase that would follow. That the MC5 ended up screaming “Mother Superior” was just sublime. We had a great time that night and it was as if the door to our future opened and that future didn’t include the nuns and Christian Bros. Bill, I remember sitting in French class listening to Brother Brian pounding some poor young man against the hall lockers, not one time, but almost every afternoon of that term. I don’t remember learning much French that year.

Belt supporter Mike Dover here. Great story! For more on those days, see the searchable Ann Arbor Sun archives: http://freeingjohnsinclair.aadl.org

I was a kid from Northeast Ohio but somehow ended up in Ann Arbor 1966-1974 and met these “righteous brothers” at 1510 Hill street.

How about a sit-in to demand the MC5 be admitted to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? Kidding.

How about a story about the early Iggy. His earlier basement band I saw in a basement; he was the drummer and vocalist.

Thanks, Mike, for supporting Belt! And both of these suggestions are great.