By Jonathan Foiles

Abraham Lincoln was a man of many talents, but interior design was not one of them. At his home in Springfield, Illinois, his bed is covered in a quilt with alternating red stripes and blue squares. The rug on the floor has stripes of red, green, and blue running in the opposite direction. The wallpaper features swirls of sepia-toned plants intertwined with bright blue tendrils. The patterns are large, the colors bold, the juxtaposition jarring. I’m crammed in this small room alongside a young fresh-faced couple and their baby who recently moved here from Idaho, a group of older women from New York and New Jersey, and a man from Decatur with a large tattoo memorializing his deceased dog. Our tour guide, an affable park ranger named Adam, informs us that this eyesore is intentional: “The design philosophy at this time was called harmony through contrast, so everything intentionally clashes. It was thought that things were more beautiful that way.”

I’m in Springfield to see the Lincoln sites for the first time as an adult. I grew up about an hour east of here in a small town of 500 people, and Lincoln was inescapable during my childhood. Just a few miles away from the house I grew up in was a cottage preserved as a historic site by the state because Lincoln and Douglas had planned out their debates in the parlor. Coming from a rural high school with limited funds, a school trip to visit some bit of Lincoln arcana had the benefit of being both educational and cheap. Lincoln looms large over our political landscape beyond the confines of central Illinois. Both liberals and conservatives find something in Lincoln they try to claim as their own. It’s difficult to think of two presidents more opposed than Obama and Trump, yet both chose to take the oath of office upon the same Bible that Lincoln used. I thought that revisiting some of the sites associated with his legacy might help me clarify who he was and what he might think about the state of our political life today.

I begin at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. It opened thirteen years ago and was the only site in Springfield I had never seen. A beautiful sunlit atrium teems with volunteers who steer visitors toward the various radiating halls which contain the exhibits. I watch a presentation called Ghosts of the Library, which uses Holavision to explain the library’s role in preserving historical artifacts. A film called Lincoln’s Eyes solemnly intones, “Lincoln’s eyes speak volumes,” and proceeds to narrate the history of his steady leadership amidst simulated cannonfire and battle noise. The library styles itself as an “Experience Museum,” so the displays are relatively light on artifacts but include life-size wax sculptures that act out Lincoln’s history. On the way out I stop by the gift shop, and I smirk as I see a collection of goods with the slogan, “I Miss Abe.” I didn’t expect a presidential museum to take such a strong stance against the current occupant of the White House. The realization slowly dawned on me that the collection could date from the Obama years when many conservatives shared the same sentiment.

The Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, IL, where Abraham Lincoln lived from 1844 to 1861. By Meagan Davsi, from Wikimedia Commons

Later I visit Lincoln’s New Salem Historical Site, a complete recreation of the nearby village where Lincoln opened his first general store and took an interest in local politics. In my memory from school trips, it is a bustling recreation of a ninteenth-century prairie village with historical reenactors sprinkled throughout, but as I arrive today in the off-season half of the buildings are closed and there are few employees around. Other than a couple only visible in the distance, I have the place to myself.

At Lincoln’s final resting place, the Lincoln Tomb in Oak Ridge Cemetery, the handsome marble memorial features a burial room flanked on both sides by corridors which contain sculptures of Lincoln and quotes from some of his most memorable speeches. Mary Todd Lincoln and three of their four sons are also buried here (the fourth and eldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln, is buried at Arlington National Cemetery). A seven-ton block of red marble displays the years of Lincoln’s birth and death. Due to an 1876 attempt to rob the crypt and hold Lincoln’s body for ransom, he is buried in a concrete vault ten feet below the surface of the burial room.

It’s hard to miss Lincoln in Springfield. Whole blocks of the downtown area are preserved as they were when he lived there as a practicing lawyer. The coffee shop where I have breakfast features a giant painting of him and sells Lincoln trinkets alongside pastries and bags of coffee beans. Silhouettes of Lincoln and his family are sprayed over the crosswalks in the downtown area, crossing Abbey Road-style in a single line. Even the hotel I stay at features a painting of a fully bearded Abraham Lincoln wearing his signature stovepipe hat and riding a bicycle. Museums and historical sites are good at telling you who a person was or narrating episodes from a life, but it’s harder to get a sense of why exactly they mattered. It’s even more difficult for a figure like Lincoln who has been dead long enough to loom nearly godlike in the minds of most Americans. He’s less a person and more of an icon. I decided to talk to some people who have been impacted by him in one way or another to get a sense of what he might mean to us now.

It’s difficult to think of two presidents more opposed than Obama and Trump, yet both chose to take the oath of office upon the same Bible that Lincoln used.

The most obvious place to begin is with Lincoln’s political home, the Illinois Republican Party. I talked with spokesperson Aaron DeGroot to find out how the contemporary GOP imagines its link to the storied past. For DeGroot, the recurring theme is freedom: “President Abraham Lincoln’s legacy is one of freedom — freedom from tyrannical institutions such as slavery, which at its heart is freedom to control one’s own destiny…. Today, the Illinois Republican Party, faced with a different set of challenges in a different political environment over a century and a half later, continues to advance the cause of freedom and empowering people.” DeGroot points not just to Lincoln’s well-known stance on slavery but also his beliefs on trade to assert that the core values of the party have always been “empowering people by protecting their rights, limiting the size and scope of government, and establishing conditions that allow the free enterprise system to flourish.”

DeGroot is not incorrect; for much of his life Lincoln was a small business owner pushing for policies favorable to free trade. For better or worse, he also captures the contradiction at the core of so much of Lincoln’s political life: the conflict between the rights of the individual and the role of the state (if any) in helping to secure those rights. DeGroot sees the Illinois GOP is bearing a special burden regarding Lincoln: “There’s a greater reverence to the principles of Lincoln … because we live in his inestimable shadow.”

It is not only the Republicans who lay claim to the heritage of Lincoln, however, so I reached out to a representative of the Democratic Party as well to get their take. Doris Turner, chair of the Sangamon County (home of Springfield) Democratic Party, also finds Lincoln a continuing source of inspiration: “No matter your political affiliation, if you have a connection to Springfield or central Illinois, it is almost certain that you hold Abraham Lincoln in high esteem.”

Acknowledging the ways in which history can obscure the man behind the legacy, Turner sees the ways in which he fought for unity and decency to be his greatest contributions to history. In her words, “he understood the plight of ordinary people because he lived the life of an ordinary man. He was human, imperfect, and willing to expose his fears, weaknesses, and failures.”

On the question of whether or not Lincoln would find a home in the modern Republican Party, Turner is circumspect: “Would Lincoln exist as a Republican today? If so, he would be an ineffective force in the GOP if he even spoke at all…He used logic, facts, and evidence as the primary fuel for his goals. Today, there remains a shrinking population of Republicans who choose to be inconvenienced with these basic elements needed for a strong, honest democracy.” Turner is quick to note that that is no guarantee that Lincoln would have been a modern-day Democrat either, but he assuredly would not fit in to the Republican Party as it exists today.

To get some perspective on Lincoln’s legacy outside of politics, I reached out to a few people who spent their formative years in Lincoln’s shadow.

Christian Shelton grew up in Springfield, and he felt proud of his hometown as a child: “I always thought Springfield was special because it was the capital city. Employment is usually related to the state government, and there’s a sense around town that people are busy.”

Shelton had the enviable position of being able to directly visit the sites which he learned about in school. Out of all of them, New Salem was his favorite, the replica village serving as a de facto time machine to a distant era. When discussing Lincoln’s impact upon our current era, he referred back to a display in the Abraham Lincoln Museum: “There’s a room in [the museum] where you can see all the news headlines and the jabs that are flung back and forth from people on both sides of the political spectrum and in between. The personal attacks of people’s character and even the way they looked were vicious.” Perhaps that time is not as distant as we think.

Shelton pointed out something else that I found notable. In an era when many adult males were mostly governed by those who owned land, it probably would seem less remarkable for a noted real estate developer to become president.

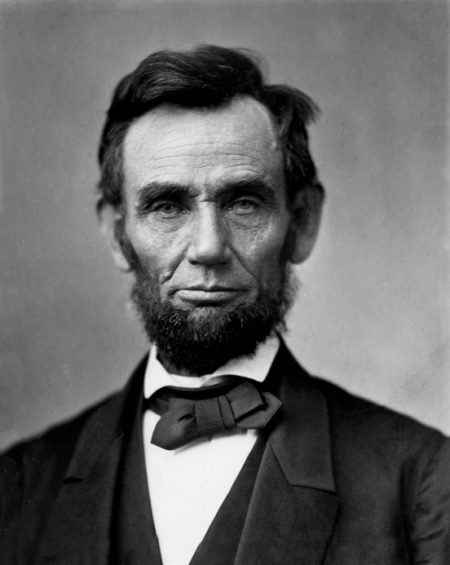

Photo of Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Gardner, November 1863 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Later I spoke with David Bromwich, the Sterling Professor of English at Yale University. Bromwich has co-taught several courses on Lincoln, but his interest in him began much earlier. According to him, “When I was a kid I memorized the Gettysburg Address, I don’t think anybody told me to. My father pointed it out to me and told me that this was a great American speech. It struck me a certain way.” From there he developed a sense of Lincoln as a great leader which he further refined as he spent more time with his writings.

He began to question the standard reading of Lincoln, best exemplified by David Herbert Donald’s 1995 biography, which depicts Lincoln as a relative moderate whose greatest gift was rolling with the times. As Bromwich sees it, such a depiction gives “the idea of Lincoln as someone who was a good navigator of the country during a difficult time but didn’t have any ultimate commitments, either anti-slavery or of any other sort, and was pretty well set on how to run the country. And I think that does an injustice to Lincoln’s consistency and to the forcefulness with which he stated and explained and, to a great extent, politically lived by certain principles.”

Bromwich suggests removing Lincoln from the line of presidents and seeing how the progress of the United States looks like from that angle. The Founding Fathers are impressive, but after their era is over the next few generations of presidents looks rather mediocre. The United States may never have attained the stature it did without Lincoln’s leadership. Lincoln helped create an ideology of interpreting the Constitution in light of the promises of the Declaration of Independence, which helped the United States begin to reckon with its original sin of slavery and offered an example of the proper use of presidential powers.

In his first Inaugural Address, Lincoln said, “A majority held in restraint by Constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. Whoever rejects it does, of necessity, fly to anarchy or to despotism.” Bromwich fears that such a delicate balance has been steadily eroded in our era, with Bush’s invasion of Iraq, Obama’s virtually unchecked usage of drone strikes, and Trump’s just about everything.

As Bromwich said, “There’s an idea of law-abidingness, keeping to precedent, that’s also the self-limitation of executive power, all of which I think we’ve seen eroded, but most of all in this current administration.”

As I’ve wrestled with Lincoln, the thing that has stood out to me the most is his ability to very publicly and decisively change his mind when he realized he was wrong. That may seem like a minor part of his legacy, but in our era of entrenched opinions and divided citizenry, switching sides can be a bold act indeed. In the fourth Lincoln-Douglas debate, Lincoln replied to concerns that he was proposing full equality between the races with the following:

I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race…. I do not understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife.

Lincoln experienced no sudden conversion when it came to race, but a glance at his final speech seven years later reveals how far he came during the course of the Civil War. He reflected upon the reconstruction process in Louisiana and proposed that “it is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.” A Confederate sympathizer named John Wilkes Booth was in the audience for that speech, and upon hearing Lincoln make the above remark he turned to his neighbor and said “that means n—-r citizenship. Now, by God! I’ll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make.” Three days later, at Ford’s Theater, he fulfilled his promise.

All of which brings me back to Lincoln’s Springfield bedroom. The United States has long been called a melting pot for its supposed ability to bring together a heterogeneous group of people and making them all Americans. Proponents of multiculturalism have rightly pointed out that the lived consequences of such a metaphor are not a happy blend of all cultures but the assimilation of all cultures to the style and preferences of the straight white Christian majority. We need a better metaphor for the American experiment, and “harmony by contrast” is perfectly suited.

Jonathan Foiles is a writer and mental health professional based in Chicago. He writes a blog for Psychology Today and has previously written for Slate. He can be reached at [email protected].

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the people of the Rust Belt, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.

Good article. One small error; I believe you mean Mary Todd Lincoln in the section on the Lincoln Tomb, not Sarah.

Thank you Rachel — it’s fixed now. Not sure how that snuck in there!