Davis, who died last month at the age of eighty, dedicated her life to LGBTQ+ history in Buffalo

By Jeffry J. Iovannone

For a long time, the only thing I knew about LGBTQ history in Western New York was one name: Madeline Davis. Growing up in a rural exurb of Buffalo during the 1980s and 1990s, I fully subscribed to what queer theorist Jack Halberstam refers to as the “metronormative narrative” of queer existence: essentially the idea that queer people from “country towns” must migrate to large cosmopolitan cities in order to lead fully-realized lives free of secrecy and persecution. My limited exposure to gay culture led me to internalize the idea that Buffalo was uninteresting and had little to offer me. Madeline Davis showed me I was wrong.

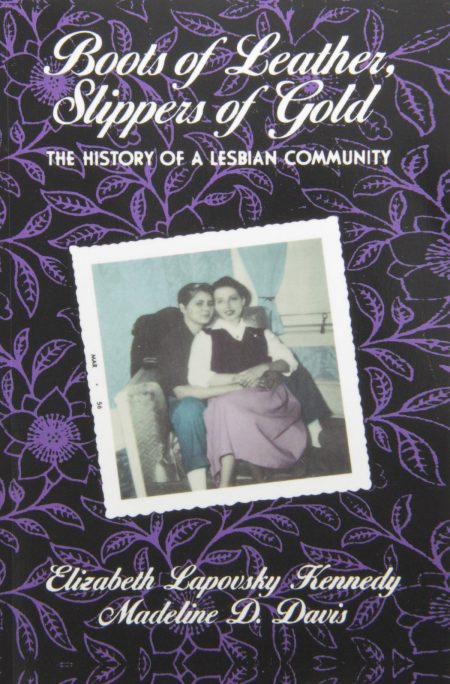

I don’t quite recall when I first heard of Madeline, but her name was a guide that led me to the history of my community. I was thirty when I began to study LGBTQ history more rigorously—the same age as Madeline when she became involved in the gay liberation movement—and it became my mission and my passion. The name “Madeline Davis” first led me to Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold, her groundbreaking oral history of Buffalo’s working-class lesbian community in the decades before gay liberation, co-authored with Liz Kennedy, and then to the Davis Archive at SUNY Buffalo State.

Photo courtesy of the Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York, Archives & Special Collections Department, E. H. Butler Library, SUNY Buffalo State.

From there, I began interviewing former members of the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier, Buffalo’s first gay and lesbian civil rights organization. I realized there were stories about Buffalo’s LGBTQ past that needed to be told, and I wanted to be one of the people to tell them. These early explorations evolved into, among other things, a book project on Buffalo’s gay liberation movement that picks up where Boots ends. Every community member I interviewed for that project urged me to talk to Madeline. But I didn’t yet have the confidence to reach out to her directly.

I first met her at a tour of her archive in October of 2018. Not long after, she broke her femur after falling out of bed. While she was recovering in a rehab facility, my friend and mentor, Carol Speser, herself a longtime LGBTQ community organizer in Western New York, suggested I give Madeline some of my work to read. I sent her selections from two chapters of the Buffalo gay liberation book. Carol reported back: “Madeline says they’re good, but you need to talk to more people in the community and keep going.” So I did. Madeline began coming to talks I gave on local LGBTQ history, and in September of 2019, I finally interviewed her at her home in Amherst, New York.

Madeline Davis was born on July 7, 1940, to a blue-collar Jewish family on Buffalo’s East Side. As in a lot of working-class Buffalonian families of the time, her father worked the assembly line at the Ford Plant, and her mother was a homemaker. A self-described “bohemian” and poet with long, raven-black hair and a magnetic personality, Davis put herself through college by performing as a folk singer in local bars and coffeehouses. She majored in English at SUNY at Buffalo and went on to earn a master’s degree in library science. Her first forays into lesbian culture were the pulp novels of Ann Bannon, which she collected and read in earnest. She began hanging out in Western New York’s gay scene in the 1950s, but did not identify as a lesbian until the 1960s, after a brief marriage to a man, Allan Romano. Her family already thought she was “kooky,” and saw her lesbianism as just another of her many eccentricities.

In the late 1960s, Davis began performing at a coffeehouse, located at 330 Franklin Street, called the Tiki. Owned and operated by James F. Garrow, the Tiki opened at a time when gay establishments were routinely targeted by the Buffalo Police Department’s Bureau of Vice Enforcement, and few existed for an extended period of time. But Garrow wanted to carve out a space for gays and lesbians in this frigid steel town on the outskirts of the midwest, and his coffeehouse soon became a popular destination.

Davis bolstered the Tiki’s reputation as a gay hangout when she began performing there as an out lesbian folksinger. She said of her music in those days: “I began changing pronouns, making coffee house owners quite nervous. I was developing a dyke following, and I could tell as they looked out of their little kitchens the owners weren’t quite sure what was happening. Much of my audience, by this time, was gay and, although I didn’t sing gay songs—were there any?—I talked gay and no other public performers around town were doing that.”

Davis’s growing reputation as a gay performer, coupled with her commanding stage presence, was largely the reason she became the face of Buffalo’s gay and lesbian community in the 1970s on both a local and national level.

Support independent, context-driven regional writing.

In March of 1970, the then-thirty-year-old librarian joined the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier (MNSF). She was an out lesbian, but did not yet see being gay as a political identity. Davis’s lover at the time, Lee Tracey, who went by the name “Shane,” asked if she would curate a small library of gay and lesbian materials in the communal space above the MSNF headquarters, then located at 70 Delaware Avenue. Davis agreed and found the job not too difficult because, at the time, there were few gay and lesbian books. She began to attend MSNF meetings and became politicized, identifying as a gay liberationist, reading the work of radical thinkers, and studying the tactics of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (later the Black Panther Party). The gay liberation bug bit her hard, and she remained active in MSNF in one way or another until the organization disbanded in 1984.

Though she became involved in the lesbian feminist movement, Davis always found importance in working in mixed gay and lesbian, and later LGBTQ, organizations. Many gay men from Buffalo saw her as a guiding force and “spiritual mother.” She participated in her first gay rights march in Albany in March of 1971. Gay groups from cities and towns across the state converged to march on the capital and lobby the state legislature on behalf of gay rights. New York City-based groups such as the Gay Liberation Front, Gay Activists Alliance, Radicalesbians, and Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries marched alongside members of MSNF. The organizers needed an upstate woman to speak when marchers reached the steps of the capital that brilliantly sunny day. MSNF’s political chair, Jim Zais, chose Davis. Ever the consummate performer, she spoke extemporaneously without a prepared speech.

On the car ride back to Buffalo, Davis, energized from the experience, wrote two things in her notebook: the lyrics to a song and a poem. The song, “Stonewall Nation,” was recorded in the fall of 1972 with financing from MSNF, and proceeds from the 45 rpm records were donated to MSNF’s gay community center building fund. The B-side contained a spoken word version of the poem, “From the Steps of the Capital, 1971.” The April 11, 1973 edition of The Advocate cited “Stonewall Nation” as the first gay liberation anthem, and Craig Rodwell, founder of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, reportedly played the record every June to commemorate the anniversary of Stonewall. Those perusing the shelves heard Davis sing pointed lyrics such as: “You can take your tolerance and shove it / We’re gonna be ourselves and love it / The Stonewall Nation is gonna be free.”

1972 was an especially prolific year for Davis. Jim Zais, inspired by her speech in Albany, devised the idea that MSNF should run her as a delegate for the Democratic National Convention. She accepted the challenge, though she thought politics were, in her own words, “pretty scummy.” Buffalo gays rallied behind her nomination, and she was selected as an out lesbian delegate from New York State’s 37th Congressional District.

Photo courtesy of the Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York, Archives & Special Collections Department, E. H. Butler Library, SUNY Buffalo State.

The DNC was held that year in Miami, Florida, in support of presidential candidate George McGovern. Davis and Jim Foster of San Francisco’s Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club were chosen to present a gay rights plank. When she took the stage at approximately 5:10 a.m. on the morning of July 12, she informed the audience that gays and lesbians “are the minority of minorities. We belong to every race and creed, both sexes, every economic and social level, every nationality and religion. We live in large cities and in small towns, but we are the untouchables in American society.” She went on to affirm her belief that all Americans deserve basic civil rights, including gays and lesbians. Though gay rights were not formally included in the Democratic Platform that year, and McGovern lost spectacularly to Richard Nixon, the fact that Davis and Foster addressed the DNC at all was a gay political milestone.

That same year, Davis and Margaret Small taught the first class focused on lesbian issues at an American university, titled “Lesbianism 101,” within SUNY at Buffalo’s Women’s Studies College. In 1978, while pursuing a second M.A. in American Studies, Davis offered a revised version of the class, focused on lesbian history, retitled as “Woman + Woman.” For the final assignment, students interviewed an older lesbian from the community and analyzed their responses. Davis shared these interviews with her faculty mentor, Dr. Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy, and the pair founded the Buffalo Women’s Oral History Project to further document the history of the community. The oral histories they collected formed the basis of Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold, published by Routledge in 1993.

In the mid 1990s, Davis embarked on her next major project: an archive to preserve Western New York’s LGBTQ past. In her introduction to the twentieth anniversary edition of Boots, she explained her motivation: “I couldn’t help feeling that Buffalo had more to offer. Many people thought we had wrung the community dry, but there were three major areas we did not set out to cover: men, transsexuals, and the community’s evolution after 1965. I knew I could not write another book… But it seemed that some attention should be paid to these topics.”

Donations of materials from community members poured in, and, in 2001, the Buffalo GLBT Archives officially took form. Originally located in several rooms of the home Davis shared with her wife, Wendy Smiley, the collection was transferred to the E.H. Butler Library at SUNY Buffalo State, and renamed The Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York, in 2009. The archive Davis cultivated is a testament to the vibrancy of LGBTQ lives in places other than large cities on the east and west coasts.

I didn’t have much exposure to LGBTQ history or culture within my formal education. I now see this is an aspect of the oppression LGBTQ people face. We are often denied access to our own histories, forced to seek them out on our own if we realize they exist at all, because they are not part of the mainstream narrative. This is especially true of LGBTQ people who live in places other than large, coastal cities. Madeline, speaking of the LGBTQ community in Buffalo, often said “we have a past, but no history.” This was true of my early experience.

As a fellow historian, I am wary of labeling Madeline as a “legend,” “hero,” or “icon.” Such terms, though seemingly complimentary, can have the opposite effect. The status of “icon” can flatten someone’s complicated humanity under its weight. Such terms also reinforce the false idea that change happens because of the efforts of extraordinary individuals, though, in most cases, those individuals are heterosexual men. Change happens when people with a common purpose come together, organize, and work toward a shared vision. Madeline could not have achieved what she did without the support and context of her community, of queer people from Buffalo.

Initially somewhat starstruck by Madeline, I came to see her not so much as an icon, but as my elder, a mentor, and a member of my community. She was both luminous and ordinary, a beacon of possibility for queer people from the Rust Belt and beyond. She showed me that being a queer historian from Buffalo was viable. She trod that often murky and difficult path so others like myself could follow. She helped me believe in the value of fighting to make unsung queer lives visible. “You can’t be what you can’t see,” the activist Marian Wright Edelman once said. Madeline allowed me to see it and be it.

The last time I spoke with Madeline was in October of 2020, after I gave a virtual talk on historic LGBTQ sites in Western New York for Preservation Buffalo Niagara. Madeline and Wendy attended, and she called me afterward to commend me and discuss the memories my research brought up. I felt myself awash in the spotlight of her attention as I jotted down her recollections. I will carry a piece of that glow with me always. Her support instilled a confidence in me that I long struggled to find. It was not long after that she suffered a stroke and was hospitalized; she died last month at the age of eighty. We always think we have more time than we do.

I do not claim to have the definitive interpretation of Davis or her legacy. History is a multifaceted stone. Turn it one way and certain parts catch the light, turn it another and new shapes and colors emerge. These different facets, together, form a complex human being, a life fully lived. Madeline understood this. Once, I asked her what she thought people should know about her and her role in Buffalo’s LGBTQ history. Here’s what she said: “What I think people should know is this: I love being gay. I loved being gay when I came out in the 1960s; I love being gay today. Being gay means being a part of something bigger than yourself to create change.”

And so she was. ■

Jeffry J. Iovannone is a historian from Buffalo, New York, who specializes in LGBTQ history of the United States. He is currently at work on a book about Buffalo’s gay liberation movement from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. Iovannone is also the co-founder of Gay Places, an initiative that documents LGBTQ historic resources in Western New York, with Preservation Buffalo Niagara.

Cover image courtesy of the Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York, Archives & Special Collections Department, E. H. Butler Library, SUNY Buffalo State.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.