By Bob Campbell

I had awakened early the morning of September 3, 1972, the Sunday before Labor Day. Most of the family was still in bed when I moseyed outside and sat my little nappy-headed butt down on the back porch.

The rays were blinding as the sun crept up and over the clubhouse located at the top of a gentle slope, about seventy yards behind our cottage on Shay Lake. The vista straight ahead was only partially obstructed by a leafy, peeling Birch tree standing at the rear of our yard like a lighthouse against a rolling lawn still glistening with morning dew. The family station wagon, a copper ’71 Chevrolet Kingswood, was parked nearby; its quad headlights staring back at me from afar.

To my left stood a twenty- or thirty-foot Weeping Willow that marked the northern edge of our lot line. The full tree, with its spreading canopy of long, flimsy branches, gave our next-door neighbor’s yard a jungle-like appearance when viewed against the backdrop of the assorted trees and shrubbery that shaded it throughout the day. The ground always felt soggy over there—partly the result of the daylong shadow across the yard and a water spring that drained slowly, I would later learn.

The air that morning was crisp and freshwater scented, the tranquility disturbed only by the soft sound of waves coming ashore. Sunday mornings were usually serene compared to the day before, because the cottage owners usually did their weekly lawn mowing on Saturdays. And the three-day weekend that Labor Day promised meant that Sunday was like a second Saturday up at the lake. With sunshine expected all day long, it was off to a glorious start.

The lake I’m talking about, just a dot on the map, is tucked away in the southeastern corner of Tuscola County in Michigan. And from late spring through early autumn, Shay Lake was the spot for many blue-collar and white-collar blacks who fled Detroit and Flint for a weekend getaway at their modest cottages. Its popularity even attracted a Detroit numbers’ man, or two, who was said to have had a place up there, too.

The author’s parents, Clarence and Rose Campbell, at Shay Lake in the 1980s. Photo courtesy Bob Campbell.

My folks had longed for a retreat of their own up north. It was a thing to do in Michigan, even for working-class people who toiled away long hours in the shop (i.e., automobile factories). But like any number of things in the fabulous ‘50s, the opportunities for cottage-ownership were restricted. Then, during a golf outing in ’56 or ‘57, daddy heard about some property on a small, undeveloped lake in the Thumb area. Though borne of the same racial segregation that characterized many of the neighborhoods in Michigan’s two greatest industrial centers, the rural enclave would become a Mecca from the early ‘60s through the late ‘80s for blacks with aspirations of a place on a lake, and some extra hard-earned money to spend.

By ’58, Mama and daddy had scraped together enough to build their little place in the sun. They were among the original settlers who transformed the lake into a recreational paradise for black Baby Boomers and their parents who had survived Jim Crow, the Great Depression, World War II and Korea.

That the inhabitants were exclusively black was of no consequence to me in ‘72. Of far-more importance, being up at the lake meant running and jumping off the dock into chilly, murky water; boating; waterskiing; dirt biking; exploring; and escape. There was also “the Clubhouse,” that mysterious hangout for the adults just off the dirt road behind our cottage, where live music could be heard sometimes wafting through the opened, screened windows on a warm summer’s night.

Shay Lake—whose forty-five acres of freshwater were filled with so many bluegills, perch, crayfish, clams and tiny shells—was at the center of my childhood and upbringing. Yet, idyllic and secluded as it was, life at the lake wasn’t untouched by the shifts occurring in the country.

On this particular Sunday—the day before Labor Day, 1972—daddy was already up and, as usual, outside doing something productive. His work there was never done. A busted water pipe in the spring to be fixed. Another leak in the flat, mid-century modern-style roof to be patched. Mowing the lawn, as well as the other odds-and-ends that come with maintaining summer cottage. And then there were the demands from the kids to be taken for another spin around the lake in the boat.

Looking back, it hardly seemed like the most relaxing way to chill after working all week as a pressroom foreman at AC Spark Plug in the department where air-cleaner housings were stamped out of rolls of sheet metal. “All week” typically meant more than forty hours. Overtime was plentiful. The auto plants were booming. And Flint, home to the world’s largest concentration of GM facilities that employed tens of thousands of well-paid hourly and salaried workers on three shifts, thrived. Though the September ‘72 issue of LIFE magazine featured a cover story, with the headline “Bored on the Job,” suggesting that all was not well on the assembly line, life in Flint seemed pretty-damn good to me. The first Arab oil embargo was still more than a year away and them sweet-ass, Flint-made, Buick “Deuce and a Quarters” were the undisputed king of the streets.

Some years later, I would come to understand how the quiet solitude of tinkering around the cottage on a nice Saturday provided a different kind of relaxation for men like my father. Eventually, I would follow his path into AC and spend some time in the same pressroom where he devoted thirty-six years of service. And though I never served in the military—unlike daddy, who endured his share of heavy combat in Italy’s North Apennines and Po Valley regions fighting the German Nazis—I thought the continuous pounding of those rows of four hundred-ton transfer presses stamping out metal canisters, that he listened to daily, and the subsequent shuddering of the factory floor in Plant 6 might be reminiscent of the thud of artillery shells exploding on some not-too-distant terrain. That environment also explained his habit of talking loud outside the shop, especially on the telephone.

Shay Lake was miles away from all that noise. Our cottage didn’t even have a telephone. The nearest one was a dusty quarter-mile away, inside a phone booth, next to a lonely utility pole with a streetlight up top. It stood guard outside the Stevens’ Store and Gas Station—“Bruh Stevens’” or “Bruh’s place,” as daddy called it—where the Mr. Goodbars, Faygo pop, and gasoline cost much more than they did at home.

In place of the drone of heavy manufacturing on that sunny Sunday morning was an assortment of composed voices transmitting from daddy’s ever-present transistor radio. The small radio—his Twitter feed back in the day—shared space on the weather-beaten wooden porch with me. AM stations still ruled the airwaves in ‘72. His listening preferences were the news and Detroit Tigers’ baseball games. So that usually meant the powerful WJR-AM station out of Detroit, and spending the afternoon with broadcasters Ernie Harwell and Ray Lane.

In the meantime, America’s role in the Vietnam War was winding down. Finally. The last ground combat troops had left Vietnam in August a few weeks prior to Labor Day. America’s part in the fight that remained mainly consisted of Air Force strikes on North Vietnamese targets, including the infamous B-52 raids—the so-called Christmas bombings—still yet to come.

The Campbells’ cottage at Shay Lake in 1962. Photo courtesy Bob Campbell.

My brother had been discharged from the Army in January, much to my parents’ relief. Mama was afraid at one point that maybe Chuck had been captured as a POW, based on some cryptic message she swore he had scrawled on the bottom of a piggybank he had sent my sister, Sherry, for her birthday. I suppose the piggybank’s primitive appearance—made out of a coconut and resembling a monkey—only fed mama’s dread about the fate of her oldest son in a war zone. But Chuck never set foot in ‘Nam, though he had been close enough to the fighting, in a remote northern region of neighboring Thailand, for his twelve-month tour of duty overseas.

I can’t be certain, but it’s likely daddy caught portions—or, at the very least, a news summary—of President Nixon’s Labor Day message, delivered later in the day on September 3. The ’72 election was just two months away. There wasn’t any mention of the Watergate burglary that had occurred several months earlier. Instead, Nixon talked about the virtues of the “work ethic” versus the “welfare ethic,” and how he wanted Congress to pass a moratorium on busing for school desegregation—something that lay ahead for Flint public schools in just a few short years. That so-called forced busing would eventually uproot my friends and me and transplant us in a faraway junior high school in a very white part of south Flint—in place of the one closer to our neighborhood, where our older siblings and their friends had attended.

News of adult issues and distant places weren’t the concerns of an eight-year-old boy, however.

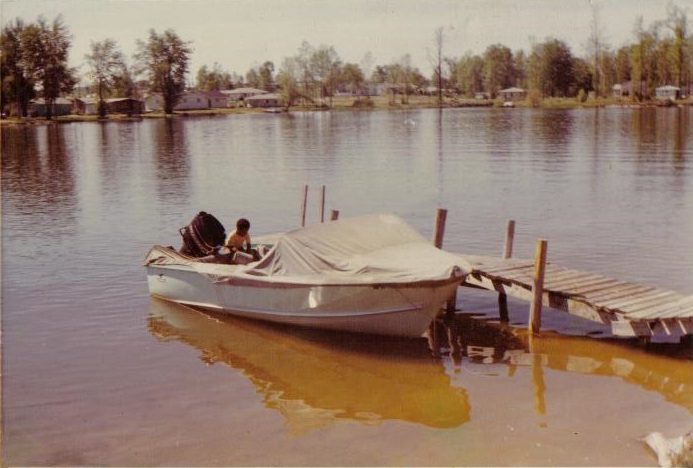

Saturday, part two, was about to get underway for me. More time in the lake, no doubt. And a boat ride, for sure. Powered by a big, black 115-horsepower Mercury outboard, our seventeen-foot, aluminum Duratech Neptune was the fastest boat on the lake. The boat’s original outboard motor was a red, forty-five-horsepower Mercury; it had been so slow that my older sisters would sometimes duck down out of embarrassment whenever faster boats sailed past us. But Daddy changed all that in 1970. Now, our boat had some serious muscle, and he and Chuck had no qualms about chopping up the water against the other speedboaters.

After some boating, maybe the water-skiers from across the lake would be out later in the afternoon that we could watch and taunt from our dock, daring them to spray us as they slalomed passed. Of course, the skiers often did spray us, if given the chance. Derrick, the doctor’s boy, and Jesse, the Bruh Stevens’ son, were really good for doing just that. And one day, I promised myself, that will be me.

Daddy emerged from around the south side of the cottage. He didn’t say anything as he went about spraying insecticide to keep the mosquitoes down. He lugged a metal tank sprayer, large enough to hold a couple of gallons of the deadly agent, with a long hose and nozzle. When he bought the sprayer, I thought it was an oxygen tank for scuba diving like the equipment on “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea.”

He approached and paused momentarily. Then he looked at me and said, “Phillip died this morning.”

Phillip was one of the older guys in the neighborhood; he lived down the street from us in Flint. A classmate and peer of Chuck and my oldest sister, Gail, he also happened to be my Aunt Marion’s stepson.

Around 1:30 a.m., August 13, 1972, Phillip and a lady friend had just left the Hammer Droppers nightclub, on north Saginaw Street, in Flint. The couple had just gotten into his car when two men approached and fired a gun three times into the driver’s side. Phillip was shot in both legs and his right hand. The woman was hit, too, in the leg—presumably by the bullet that had passed through his right hand.

I don’t have clear memories of the shooting. I recall that there was something said about how two guys had been leaning on Phillip’s car—a Deuce, maybe?—when he came out of the nightclub, and the dispute escalated. I also heard that maybe there was more to the story than that.

Whatever the reason, it was big news in the neighborhood. Things like that just didn’t happen to people who lived on and around Maybury. It even made the crowded section-front of the August 14, 1972 edition of the Flint Journal. “Man and Woman Shot After Entering Auto,” the headline read. The story was two, maybe two-and-a-half column-inches long. Just the facts. The four Ws—Who, What, When, and Where. The Why went unanswered. The suspects “ran west on Edmunds,” the article stated.

How did daddy know that Phillip had died that morning? He had heard the news on the radio while up at the lake.

The last time I recall seeing Philip was on our street, Maybury. I don’t remember if the encounter occurred in ’72 or the year before, or the year before that. But I do remember that he was tall and athletic. I was little; so short, in fact, that I was always at the front of the line in school whenever the boys were made to line up from shortest to tallest. Phillip was light-skinned and handsome, with his big Afro and wispy mustache. I’m sure that all the girls said that he had good hair and that he was fine, too.

When I saw him last, Phillip had just returned home and had gotten out of his work truck. An electrician in his father’s electrical contracting business, he was dressed in his work uniform. The shirt was light blue. Sky blue, we used to say, in the way the sky appears on a sunny, cloudless day. “What’s happening, Bobby?” Phillip said—like he really knew who I was, like maybe I was somebody and not just some anonymous little kid.

As a little boy, I never, ever knew how to respond whenever an older dude from the neighborhood said to me: “What’s happening, Bobby?” Thinking it was a real question—instead of a casual greeting shared among soul brothers—I took it literally and would respond with “nuthin’” or “I dunno,” punctuated with a naive shoulder-shrug. This goofy response would often trigger a grin or a chuckle from the soul brother doing the asking. Phillip gave a faint smile and kept moving.

The author as a boy at Shay Lake. Photo courtesy Bob Campbell.

After the shooting in August of ’72, Philip had made it three weeks before succumbing to his wounds. When daddy told me, his expression was matter-of-fact, as if to say, let’s try and make the best of a bad situation. A look of resignation, when hoping for the best fails to deliver. A masculine sadness, I suppose. Once I knew, it was as though daddy had said to me: What’s happening, Bobby?

I didn’t know what to say.

At the time, Phillip was just the second person I’d known personally who had died. My cousin Paul was the first. He had died a year earlier, at Mott Children’s Hospital, in Ann Arbor, from leukemia. Paul was fourteen, and, for some time after his funeral, I thought pallbearers were called Paul-bearers, perhaps named in honor of the deceased. By the time of Phillip’s death, however, I had learned a few more things.

Daddy didn’t linger around afterwards. He didn’t use Philip’s death as a teaching moment, like some kind of black Mike Brady explaining the harsh ways of the world to little Bobby. He didn’t have to. His silence from that moment forth was plenty. He resumed spraying for bugs and disappeared around the north side of the cottage, toward the shortage shed.

I don’t remember what I did the rest of that Sunday. It probably went more or less according to my plan: another dip in the lake; a boat ride; maybe watching my idols slalom across the dark water a few more times to close out the summer. That night, I probably gathered around the TV with my sisters and niece to watch the Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Telethon on Channel 5, the only reliable station we could get up at the lake. We would try to see how late we could stay up for the all-night show.

On Monday afternoon, September 4, 1972—Labor Day—the family packed up the Chevy station wagon and left Shay Lake to head back to Flint. Summer playtime was over. Autumn was at hand. ■

A version of this essay first appeared in Gravel Magazine.

Bob Campbell’s nonfiction has appeared in Belt, Forge Literary Magazine and Gravel Magazine. He is a contributor to Belt Publishing’s Midwest Architecture Journeys, coming in September 2019. His debut novel, Motown Man, will be published this fall by Urban Farmhouse Press. He was born and raised in Flint.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.