Data Visualization by Evan Tachovsky

Text by Anne Trubek

An enormous tree engulfs my front lawn. I do not know what kind of tree it is. If I am outside working in the garden and a tree-knowledgable person walks by, she inevitably asks me, “What kind of tree is that?” Although I pride myself on identifying perennials, I am tree-clueless. So I just tell her what others who have passed by before have suggested: “Maybe a kind of dogwood? Maybe a linden?”

I may not know the genus, but I do love that tree. And not just the one on my lawn: my block, my neighborhood, and my city, Shaker Heights, are shrouded by huge trees. Recently I realized these trees are keeping me a prisoner of sorts. A few months ago, I started thinking about moving to the city of Cleveland proper (the closest border is about one mile away). But I kept rejecting the idea, because, as I surprised myself by thinking, “I’d miss the trees.” I did not know until that moment how important trees are to me. My relationship to them is subconscious, only bubbling up to the surface when I think about their absence.

My city knew this would happen: that trees would keep people rooted was part of its scheme from the beginning. Inspired by the Garden Cities movement, Shaker Heights was planned the early years of the 20th century to mingle rural with urban. Parks, required building setbacks, and green spaces were worked into the initial plans and construction. In 1927, a zoning ordinance was passed that required all curbs — known in these parts as tree lawns — to be densely planted with maples, sycamores, and other large, leafy trees.

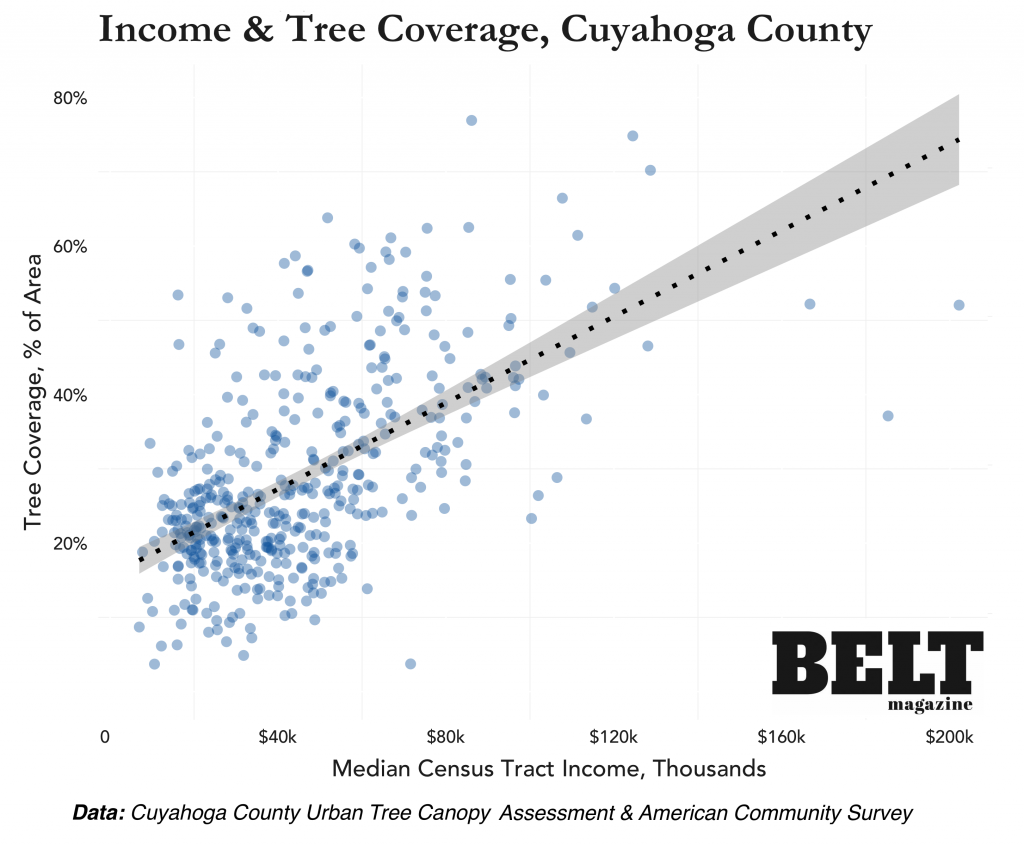

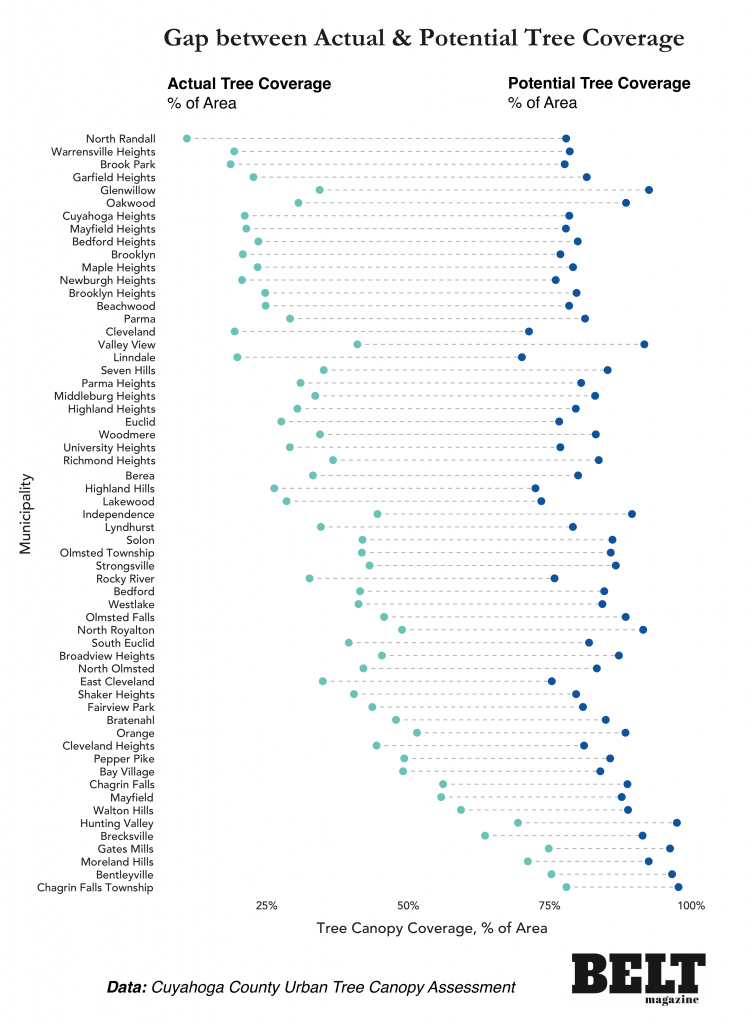

Shaker Heights’s planning followed the precedent set by Cleveland itself, a city nicknamed the Forest City after its mid-nineteenth century ordinances, passed by Leonard Case, Sr., then Cleveland Village Council President, to plant shade trees. It was once quite a leafy city. But whereas Shaker Heights has continued its attention to canopy cover, Cleveland has not. Today, differences between the two cities — and between various municipalities in Cuyahoga County — can be told not only through poverty levels and school district report cards but also through the number of dropped leaves. Turns out income levels and canopy cover are connected, not just in Cuyahoga County but across the nation.

The charts show how strongly income and trees are correlated, as well as the connection between potential canopy cover and income (we would not want to plant a forest at the airport, for instance). In the green hexabins map below you can clearly see the outline of the city of Cleveland–distinct from its neighbors by its lack of trees. The Income & Tree Coverage chart shows how those neighbors in Cuyahoga County fare economically in relation to their tree cover, and Gap Between Actual & Potential Tree Coverage charts how much each municipality could improve.

So, what can be done to increase the numbers of trees in the more barren parts of the county, places where potential canopy cover is high? The Western Reserve Land Conservancy has a simple idea: plant more trees. To do so, they hired an “urban lumberjack,” arborist Colby Sattler, to help plant thousands of trees in the city, train residents in maintenance and arboriculture, and host events to promote their initiative. They did not have to look far — or go too deep into their pockets — to find the saplings: the stock for this spring’s planting comes from foreclosed nurseries.

To plant trees requires an act of faith: you do backbreaking and thinly funded work to benefit others — most of whom are not yet born. It will be years before newly planting saplings will throw off enough shade to keep passersby cool in summer. It will be decades before some clueless woman will say, “I don’t know what it is but I love it!” of the tree in her front lawn, or decide to stay in a city because of the leaves — not ever realizing the benefits of those trunks to her health, well-being, and checking account, or knowing who it was that once decided to train the previous owners of the house how to water and feed the roots.

This Arbor Day (April 24), look around, and count the trees you see. If you can, get to know them by name. We’ll help you get started with our “State Trees of the Rust Belt” illustrations by David Wilson, which you can view here.

Evan Tachovsky is a data analyst based in New York City and originally from Northeast Ohio. He’s on Twitter @evantachovsky.

Anne Trubek is the Founder & Publisher of Belt.

Belt is a reader-supported publication. Become a member now — we offer great perks! https://beltmag.com/product/belt-membership/