How youth organizers in Chicago laid the groundwork for contemporary calls to defund the police

By Kiran Misra

On July 3, 2017, former Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel announced a plan for the construction of a new “public safety training facility” on the west side of the city, a $95 million expenditure toward what was already one of the most well-funded police operations in the country. Emanuel perhaps hoped the news would go unnoticed amid Chicagoans’ Fourth of July celebrations—and it probably would have, if activists hadn’t drawn attention to what seemed like suspicious timing for the announcement, a lack of community input, and the changing messaging around what, exactly, the facility was intended to do.

Earlier that year, the United States Department of Justice had issued a federal consent decree mandating reform in the Chicago Police Department (CPD) after decades of corruption and unconstitutional practices. Emanuel claimed that the creation of the academy was an essential part of complying with the decree, despite the fact that only one of the report’s ninety-nine recommendations mentioned anything about CPD’s training facilities. Explanations of how the academy would be funded were vague. Julienn Kaviar, a spokesperson for the city of Chicago, said: “the city will identify funding as the project progresses.”

This was a red flag for residents not only in West Garfield Park, where the facility was due to be constructed, but across the city. In the years before the announcement, Chicago saw dozens of schools in Black and brown neighborhoods shuttered, social services slashed, and numerous economic development and violence prevention programs ended due to an ongoing budgetary crisis. West Garfield Park, which had the city’s highest violent crime rate, and where young people experienced daily surveillance from the neighborhood’s overwhelming police presence, was especially hard hit.

“West Garfield Park is violent because there are no resources, no jobs,” said Destiny Harris, who was a West Garfield Park resident at the time. “My elementary school was one of the schools that Rahm closed down in 2013. The fact that the only investment the city was willing to make in my neighborhood was these $95 million dollars for the police academy rather than all the other things they could have supported that we need…that’s part of the problem.”

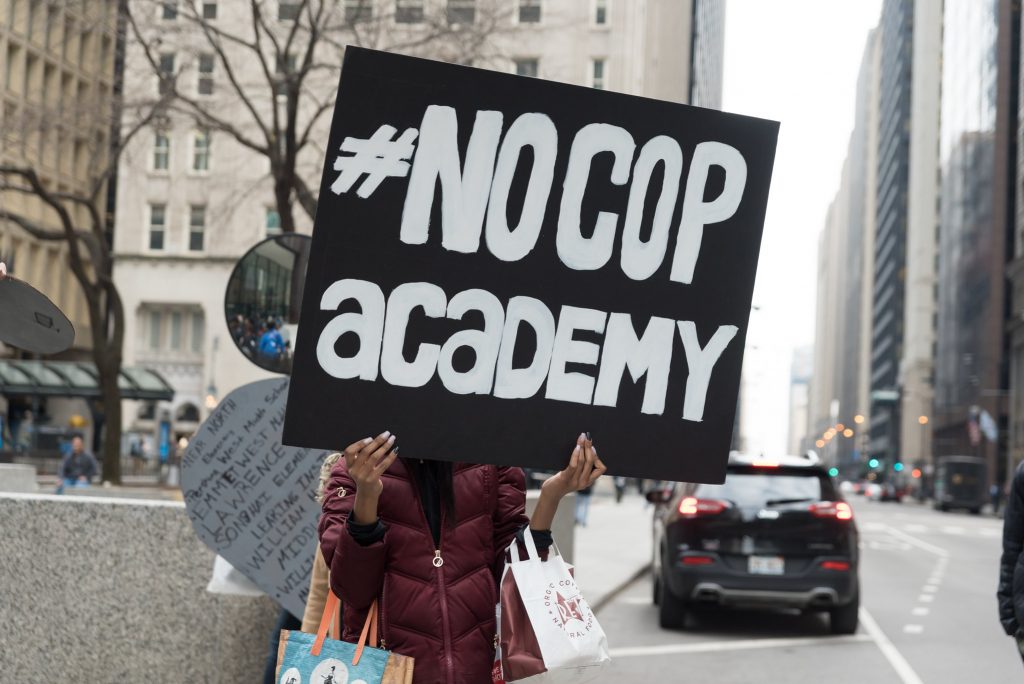

“You end up feeling like a criminal just for being in your own neighborhood,” Citlali Perez, another youth organizer, explained. “We wanted to build towards a society where we’re not targeted for living where we live.” Perez and Harris soon joined other members of their community in organizing against the construction of the facility, developing one of the most innovative and robust abolitionist campaigns the United States has seen in recent years, known as “No Cop Academy.”

Organizers and supporters of #NoCopAcademy, many of whom were CPS high school students on spring break, hold a “die-in” in the lobby of Chicago City Hall on March 28, 2018. Cardboard tombstones bear the names of people who were killed by Chicago police, as well as the names of the schools and mental health clinics closed by Rahm Emanuel’s administration. Photo by Love + Struggle Photos.

2018 National Youth Poet Laureate Patricia Frazier, who was a student at Columbia College at the time of the campaign, remembers how her organizing collective, Assata’s Daughters, decided to fight back. “One of the girls in Assata’s, Brianna, was from West Garfield Park and was concerned about the cop academy. We thought [organizing against the construction of the academy] would be a good campaign not only because of the dangers of increased police presence in West Garfield Park, but also because this academy relates to so many other things we cared about. Six of the fifty schools Rahm closed in 2013 were in West Garfield Park. All [public] schools in Englewood were closed because of the budget.”

This, ultimately, is the argument behind most calls to defund the police: that the money allocated for policing would be more effective if applied elsewhere, including toward things like education, mental health services, and housing, which could prevent and address the root causes of crime and conflict.

“Abolish the police sounds pretty radical, even to people that identify themselves as leftist progressive,” said Benji Hart, an adult mentor with the No Cop Academy campaign. “But we realized that if we said, ‘If we had $95 million for this, why don’t we have it for that?’ [That] was something that was very easy for more folks to kind of get behind. Using that really specific example of this new facility helped open up the conversation in a much more accessible way.”

Perez, a sophomore at the time, remembers hearing about No Cop Academy from classmates at her high school. She started attending daily meetings for the campaign after her classes, her first introduction to organizing in Chicago. She recalls participating in actions like train takeovers and a die-in at City Hall, but also remembers learning the basics of organizing as a youth organizer at coalition meetings. “During the campaign, we talked about how organizations end up tokenizing youth and having them in pictures, but not actually having them involved in making decisions,” Perez explained. “No Cop Academy was a good example of how to have a campaign actually be youth-led and adult supported.”

“Young Black and brown folks were at the forefront of the movement,” said Caullen Hudson of Soapbox Productions, a media company involved in No Cop Academy organizing. “Young people are really targeted by the police, they’re most affected by funding going to the police instead of schools. They’re the ones that are going to be most charged about [abolition] and provide the best solutions, because they’re the most marginalized in this specific fight.”

The result was an innovative collection of actions, many of them reaching Chicagoans who had not previously considered abolition or discussed the problems with policing across the city. A group of Muslim No Cop Academy campaigners gave out flyers at Rahm Emanuel’s iftar; Chance the Rapper sent organizers pizza during a die-in at City Hall; and, during a Halloween train takeover on the CTA, organizers talked with commuters about the consequences of the academy over trick-or-treating spoils. On their days off of school, students marched to their aldermens’ offices to explain their views on the police academy, and organizers even shut down I-290 (the Eisenhower Expressway) to draw attention to the cause.

Many of the young people and adult allies involved in the campaign were artists who saw the creation of public art and creative works as integral to any movement, so hosting open mics, making buttons and t-shirts, and creating installations across the city were central facets of the campaign. “No Cop Academy showed that organizing isn’t just one thing. It’s not just people out in the streets, it’s not just voting, it’s not just making art, but it’s a robust, interdisciplinary, inter-generational fight that needs all tools on deck, all people on deck,” Hudson said.

Organizers also pushed community members to imagine what could be possible with new funding priorities. Most weekends, they canvassed neighborhoods in the city to ask residents about how they would like $95 million of their taxes to be spent. Another canvassing effort, in which the campaign interviewed five hundred Garfield Park residents about their views regarding the construction of a police academy in their neighborhood, resulted in the publication of a robust, data-driven report, which was presented in front of Chicago’s City Council.

“It was in that generative nature and that focus on creation and creativity that No Cop Academy demonstrated its most abolitionist commitment,” Hart told me. “At our train takeovers, we had a white board and asked people what they wanted to spend $95 million on in their communities. It wasn’t just about ‘We don’t want this academy built.’ It was about: ‘Here are all the things that West Garfield Park wants instead.’…No Cop Academy both pointed to the hypocrisy of local government and kind of pulled that curtain back, but also showed people what is possible and what can be.”

In 2014, when protestors took to the streets to protest the police killings of Laquan McDonald, Mike Brown, Rekia Boyd, Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, and countless others, cries to “indict, convict, and send the killer cops to jail” echoed across the country. Calls for mandatory body cameras, streamlined complaint systems, and greater racial diversity in police forces soon followed. In the following years these and other reforms did little to reduce racial bias, excessive use of force, and lack of accountability in police departments across the United States.

No Cop Academy demanded a radically different type of change—a reallocation of resources away from policing. “When people ask [in 2020], ‘why are people calling for these things all of a sudden?’ The reality is that we’ve been having these conversations for years,” Harris said. “We’ve been saying that police don’t keep us safe. No matter how many more resources we give them, they’re not suddenly going to start being able to change that.

Harris, who attended high school next door to the existing police training academy, remembers hearing raids and mock shootouts during her classes and lunch breaks with no warning from the officers next door. “Challenging the idea that policing equals public safety was one of the biggest things that we did, letting people know that you don’t need police to feel safe,” Harris said. “Now people are saying, ‘wait, maybe police don’t keep communities safe.’ They’re saying, ‘let’s draft a new city budget, take funding away from CPD, we need to get cops out of schools.’”

But the fight wasn’t easy. Over the course of the campaign, there were several intermediate City Council votes and hearings before the final approval of the construction contract—for zoning changes, land purchases, fund transfers, and more. When organizers attempted to testify at these City Council meetings about how the academy would affect their communities, they were forcibly removed. When young Black activists went to a Black Caucus fundraiser challenging Black alderman to support the campaign, they were met with threats and ridicule from their representatives. When they attempted to meet with their elected officials in advance of the votes., they faced locked doors. And at every step, organizers had to contend with the city’s secrecy surrounding its plans for the academy. (Eventually, then filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request lawsuit against the Mayor’s Office for withholding documents involved in the cop academy plans and sued the city for violations of the Open Meetings Act.)

An activist marches outside of Chicago City Hall on March 28, 2018. Photo by Love + Struggle Photos.

Perez said this was all part of her education. Organizers in 2017 and 2018 worked to ensure that the campaign was accessible to anyone who wanted to get involved. “Going into No Cop Academy, you didn’t have a major experience in organizing and be familiar with City Council and stuff…Along the way we became familiarized with how the city works and how different tools can work in organizing,” she said. Three years later, she’s still organizing for racial justice, now as a college student.

The campaign’s diverse coalition of supporters included many groups that didn’t (and still don’t) identify as abolitionist but were united in the common goal of drawing citywide attention to the disconnect between city budget priorities and community needs. Groups involved in the campaign included youth groups, senior citizen alliances, neighborhood councils, organizing collectives, arts organizations, service providers, racial justice groups, and more. And according to organizers, the understanding that groups didn’t have to agree on everything to work together forged connections that have been maintained to this day, with many collaborating again in the last few months.

The most important commitment of the campaign was making sure that new people were being brought in, specifically young people, and that they were being trained up as organizers in their own right,” Hart explained. “Which meant that young people were making decisions about what is the next step, asking ‘how do we respond to this thing that the city has just offered?’”

In March 2019, Chicago’s City Council voted to move forward with construction of the academy, with thirty-eight Councilmembers voting in favor. But organizers still consider the campaign a win. At the beginning of the campaign, only two aldermen had expressed reservations with the academy’s construction, and one of them, No Cop Academy champion Carlos Ramirez Rosa, was kicked out of the Council’s Latino Caucus for his opposition. But when the final votes were tallied, eight aldermen—some of whom had voted for the construction of the academy at previous City Council meetings—voted against the contract and zoning changes for the new building.

“Folks who say ‘hey, you lost the vote, therefore you lost,’ are not folks who understand how organizing works,” Hudson said. Hart added: “The first press conference that we had was attended by something like fourteen people. And by the end…over a hundred organizations in the city were endorsing the campaign. Since then, there have been mass organizing efforts in Chicago demanding the defunding of the police department, demanding the reallocation of resources. People who never said, ‘abolish the police’ before are suddenly openly saying ‘abolish the police.’”

Years after the campaign, as calls to defund the police have reached a fever pitch across the country, Chicago stands out as one of the only major U.S. cities to take no steps towards defunding its expensive police operations. But the pressure on city officials to rewrite the city budget is mounting, in part due to the work of educators with No Cop Academy, who spent almost two years engaging Chicago residents in a citywide conversation about what a just budget would look like and training a new generation of activists in the process.

“If we understand this as a long fight, as a long term, multi-generational battle, we can think about campaigns as spaces where people learn and build relationships,” Hart said. “The point isn’t to win. The point is to build power. The point is to strengthen community resolve. The point is to change the narrative. The point is to bring in new people. Even though we lost those votes in early 2019, to see this current movement nationally taking on the demand to defund police is a much, much greater victory in some ways.” ■

Kiran Misra is a journalist, policy researcher, and organizer working for the United Nations World Food Programme in Rome, Italy. She primarily covers Chicago’s civic systems and South Asian culture across America. You can find her on twitter here or online here.

Cover image: Organizers in Chicago City Hall on March 12, 2019, the day city council members voted to move forward with building the police academy. Photo by Love + Struggle Photos.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.