Thompson captured photos of the place — the hills of WVA folding into each other like origami, holding mist and dew in the hollows. And he staged new photos which conjure these working men, bearing up under hours of physical labor, covered in white dust, looking otherworldly but also fully human and integral to the achievement.

By Jody DiPerna

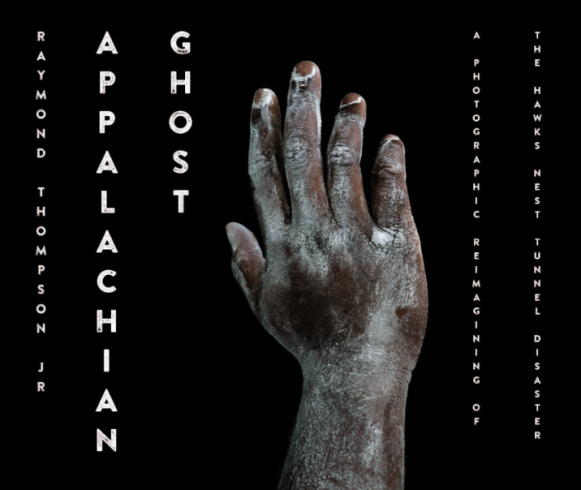

When Raymond Thompson, Jr. started looking through the archives of the Hawks Nest tunnel, he was struck by how absent the five thousand plus men who worked the dig were. It was, rather, a celebration of the engineering feat and the important men involved. Thompson’s new book, “Appalachian Ghost: A Photographic Reimagining of the Hawks Nest Tunnel Disaster ” (University Press of Kentucky, 2024,) is a photography collection that provides a necessary corrective while doing some heavy archival lifting.

By focusing the workers through his own craft and virtuosity, Thompson has created a beautiful record that is lamentation and resistance, history and hymn.

The Hawks Nest Tunnel was about three-quarters of a mile long, dug to divert water from New River to a hydroelectric plant at Gauley Junction, West Virginia. Ground was broken on March 31, 1930. Even by the standards of the day, working conditions were atrocious. Rudimentary safety measures (wetting the dusty rock face or just waiting between shifts for the dust to settle) were ignored or otherwise evaded and workers inhaled prodigious amounts of powdery white silica dust every minute of every shift.

They looked like apparitions as they walked back to the shoddy housing thrown together in the mining camps where most lived. Thompson thought about these living ghosts all the time.

By the time the tunnel opened four years later, there were reports of scores of miners dead and more dying. It is estimated that 764 men who worked Hawks Nest died of silicosis.

Thompson first encountered the tragedy in 2019 when he was working as a photographer and videographer at West Virginia University. That year, WVU Press released a new edition of, “The Book of the Dead,” the epic poem by Muriel Rukeyser published in 1938 which documents the Hawks Nest tragedy. Because of that, Thompson met Catherine Venable Moore, a writer and researcher who wrote the introduction for the 2019 Rukeyser publication and who has immersed herself in Hawks Nest stories for years. She contributed the introduction to “Appalachian Ghost,” as well.

“What I love about Catherine’s (Venable Moore) writing about it and Rukeyser’s work — they center the worker. Not looking at this marvel of modern engineering, but saying, there are these men who did this work,” Thompson said. Like Rukeyser and Venable Moore, it was the workers who captivated him as well.

He and Venable Moore went to Hawks Nest together. You can see the cemetery from Route 19 as you approach the dig site. It was a particularly ample summer and the cemetery was overgrown and lush. Thompson said that through the growth, you could still see the tops of the simple firewood crosses. From there, they zigzagged down switchbacks to get to the dam itself, which sits below the burial grounds in a rocky area.

“The locations have a kind of power to them,” Thompson said of this first visit to land soaked in the dead.

“It’s just a really strange feeling to be down in that space, in the sound and the mist. All that stuff sort of touched me and inspired me. It was all very impactful.”

He started driving down when he could, but he also dug through the archives, searching for photographs and other documentation. As he excavated the story of the place, found articles and images, and visited this hallowed ground, Thompson gathered ingredients to make his own new work. “Appalachian Ghost” is a collage in book form — a multidisciplinary exegesis — as Thompson blends his own photographs with archival photos and maps, a Rukeyser excerpt and the poem “Appalachian Ghost,” by Norman Jordan, for which this book is named.

The Dust #5, photo by Raymond Thompson, Jr., 2019

Between 2019 and 2023, Thompson captured photos of the place — the hills of WVA folding into each other like origami, holding mist and dew in the hollows. And he staged new photos which conjure these working men, bearing up under hours of physical labor, covered in white dust, looking otherworldly but also fully human and integral to the achievement.

“How do I make it dusty and foggy?” is what Thompson found himself thinking all of the time.

“I tried to imagine what a drill does when hitting rock, but also, what’s the beauty of all of that? I love when it’s foggy. I go for a walk and I can see certain things — see something I’m familiar with but in a completely different way,” Thompson said.

Of the approximately 5,000 men who worked the dig, about two-thirds were Black men, and, according to Thompson, these were mostly men who had come north from the deep south to work.

“I read somewhere that the reason why they hired Black migrant workers was because generally ‘West Virginia negroes were too rowdy’ — more likely to pull a gun than to listen,” said Thompson.

That could be fact or mountaineer legend, but either way, it feels right — West Virginia miners of all races were known to be rowdy. The West Virginia Mine wars stretched from 1912 when violent battles occurred between workers and hired thugs along Paint and Cabin Creek and stretched through the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921. West Virginia miners and their families, both Black and white, fought for fair pay and fair housing and took up arms in the face of armed forces hired by draconian mine owners.

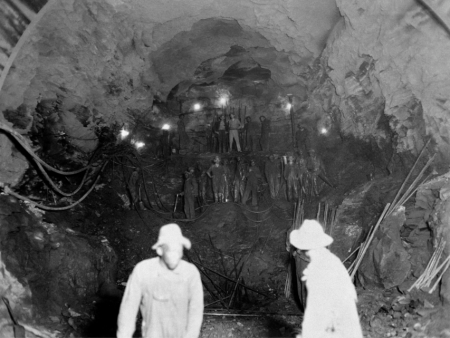

Included in “Appalachian Ghost” are some of those archival photos from the West Virginia Archives & History housed at the Capitol Complex in Charleston. Thompson was both surprised and disappointed to find that the photographs documenting the dig are photocopies. He said that the negatives were made from nitrate which is an intense fire hazard.

The lack of the originals makes it hard to really interrogate these photos; Thompson noticed that the photos may have been altered using the practice known as “dodging” — altering photos to obscure part of the image while bringing other aspects into sharp relief. It looks a bit like old fashioned soap opera style, racking the focus to blur one person and bring another to sharp clarity, a technique used to hand-hold the viewer and make sure they are looking where you want them to.

“I imagine someone from Union Carbide needed a picture for a report and wanted to make sure that certain people stood out who were important, that you could see them. Anything that is super bright is what you’re meant to see first,” Thompson explained.

Those are traditional techniques used since the advent of the medium, but there are other instances where it looks like people in the photos have been rubbed out. It actually looks like somebody went through with a graphite pencil or a piece of charcoal to cover or obscure certain people from the frame — a photographic manifestation of the practice of erasing working people and specifically Black people all through Appalachia.

“I was curious because I wanted to see if there had been any actual changing of the negatives or scratching out of a few images or one image that I found. I wanted to see if someone had gone in and messed with it in some way,” said Thompson.

There is one archival photo in which two workers pop up in the foreground — they are Black men and it really looks like they photobombed the shot long before we had the term photobomb. The picture obviously wants you to look at the man in the white shirt towards the center of the frame. It’s one of Thompson’s favorites because “the workers have clearly broken a rule,” and this bit of rebellion is joyous.

Tunnel No. 249, View of Heading No. 4, showing the drilling crew.

photo courtesy of Raymond Thompson, Jr.

Without the negatives, without the original photos, he can’t say that the photos were definitively altered, but they all center not just white men, but managerial white men. Why would we need to see the actual laborers?

In a way, with his work, Thompson is undodging those old images, focusing on the men who were obscured, unthinkingly or deliberately.

Sometimes, when I mention Hawks Nest to people, they assume it was a coal mine, as most mining endeavors in West Virginia were. This was not that. This was all done to power all of Union Carbide’s operations throughout the state, to use the Kanawha River to fuel their plants. You can see it if you work your way down the river, says Thompson.

“I knew that there was a power line that connected all of them. I discovered it because I was looking at Google Earth Pro, and connecting the power lines, from that to that, from that to that,” he said. And he thought, “Oh, my God. They did this in 1941. It’s in this picture.”

Thompson sent an illustration pulled from Fortune Magazine circa 1941. It shows the river and Hawks Nest and all the power is flowing down from the site of the tunnel to Charleston. The text of the 1941 Fortune story says, “Fewer people know the extent to which Union Carbide, the $365 million giant, has made the Kanawha its own.”

Seven hundred sixty-four lives laid at the doorstep of powering Carbide’s operations.

An artist’s discipline is sometimes what is needed to turn data — 5,000 workers, 764 dead — into something else, something that moves us, that we cannot shake or put aside. Thousands of Black men moving into a rough mining camp to work a dig. Hundreds of those men dying from silicosis, feeling like the weight of the Appalachian mountains are collapsing their chests. Thompson brings these men to life and honors these lives through art.

Open this book and enter into a wholly new exploration of a hundred year old tragedy, the men, the place, the project, the needless suffering and the way that nature adapts, adjusts and reclaims.

Raymond Thompson will present work from his book APPALACHIAN GHOST at Bottom Feeder Books in Point Breeze, Pittsburgh, on Friday, June 21 at 6:00 p.m.

This article has been republished by the generosity of the Pittsburgh Institute for Nonprofit Journalism.

Jody DiPerna lives, reports and writes from her home in Pittsburgh. She is an award winning

journalist and one of the founders of the Pittsburgh Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Currently,

she is researching a book about the importance of reading, writing and literary life in Appalachia for West Virginia University Press. She conducted one of her finest interviews in a rural laundromat.