By Tim Kiska

The building at Mack near Chalmers resembles thousands of Detroit properties: abandoned, in tax foreclosure, burned-out, dangerous, overdue for demolition. The surrounding east-side neighborhood comprises 3,430 vacant lots and a mere 1,289 buildings – only 900 or so occupied. Two carjackings recently occurred just down the street. Last year, one block away, a man dressed in camouflage emptied an automatic weapon into a parked carload of suburban teens, killing one and wounding three. The shooter left 30 empty shells on the same corner where my friends and I bought ice cream some years ago.

The burned-out hulk at 14526 Mack Avenue was once my home. My father’s business, Edward F. Kiska Jewelers, occupied a small storefront during most of the 1960s. For two years, our family lived there. My father and mother slept behind the shop. My two sisters, two brothers, and I slept upstairs. At night, I’d hang out with my buddy, Wally Koster, who clerked at the liquor store across the street, where he would intrigue me with stories about life at the University of Detroit. My living room overlooking Mack Avenue is where I played “Sergeant Pepper,” over and over and over, when it was released in 1967.

Since then, history has landed hard on my block. The end for my father’s old store involved 25 firefighters and seven rigs. An arsonist climbed the stairs four months ago and torched my brothers’ old bedroom above the alley. The street façade doesn’t reveal the real damage in the back, but smoke residue can be seen around my old bedroom window.

This wrecked building, which went out belching smoke into the spring air, is a snapshot of my blighted city. What city anywhere lost more than a million people, other than to war or natural disaster? The net outflow, all in my lifetime, surpasses 1,200,000. That’s half a million more people than the American combat deaths in all our wars, almost as many people as the population of Dallas, Texas. Fully understanding the flight of more than a million people from the cradle of America’s blue-collar middle class will require generations of research. But the storefront on Mack Avenue tells a lot about the grit and energy that has driven Detroit for the better part of a century.

But forget these numbers for a second. It was my home. So I guess I take it personally.

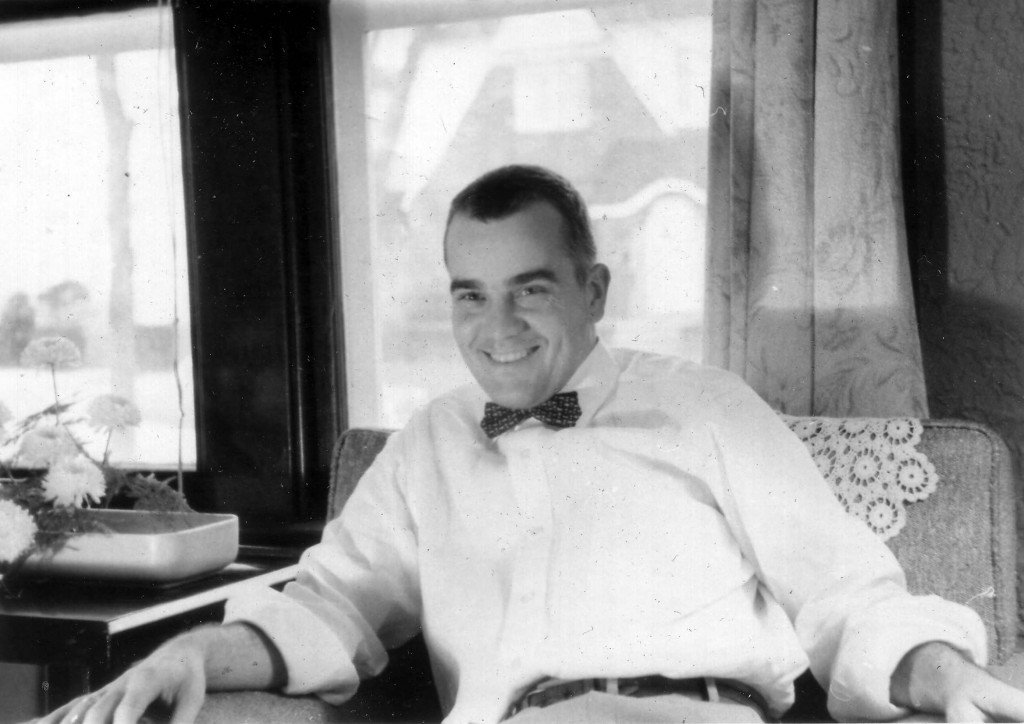

My father came to southeast Michigan from Pittsburgh in 1951. Detroit offered more jobs, and had a lot more people – two million within the city limits when Ed Kiska arrived with my mother, Mary. My father was a World War II veteran, the son of a Polish immigrant who worked in Pennsylvania’s coal mines. My mother was the daughter of a railroad purchasing agent. My father learned to fix watches at a Pittsburgh trade school. Always, he ached to own his own business. After 13 years of working for other people in Detroit, he rounded up enough money to buy Art Senave Jewelers.

Art was the only person I knew who had first-hand experience with World War I. He was also part of the great middle-class boom traceable to 1914 and Henry Ford’s Five-Dollar Day. After the war, Detroit’s population doubled in ten years as it achieved dominance in the global automobile business. Nearly one-third of the city’s population was born in another country. Ford listed 47 different immigrant nationalities among the workforce at its Highland Park plant, where the Model T was built. There were Poles, Italians, Romanians, Lithuanians, Syrians, Macedonians, Luxembourgers, Boers, and Manx. Detroit’s prosperity also drew a surprising number of Belgians, among them Art Senave.

My father related the following story to me several times, always in wonder. Senave (pronounced suh-NAVE) was a teenager in the final days of WWI. His job was to care for a horse belonging to a rural doctor. Everything had spiraled into chaos and Art was stuck hundreds of miles from home. So he walked. Toward the end of his days-long long trek he approached a bridge guarded by a German soldier. The war had not formally ended. When ordered to stop, Art thought he was about to die. The German asked Art where he was going. “Nach Hause gehen,” Art said: “Going home.” The soldier shook his head wistfully, and whispered “nach Hause gehen,” then sent Art across.

By 1920 some 6,000 Belgians had settled in Detroit, mostly on the east side, where they became known during Prohibition for the quality of their speakeasy beer. The most famous descendant of this enclave, now scattered everywhere, was New York Knicks star Dave DeBusschere, whose father Leon was an immigrant.

Art Senave set sail for Detroit and landed in New York on New Year’s Eve 1919, little more than a year after walking home from the war. He took a job at his uncle’s jewelry store on Mack Avenue and quickly established himself. He set up shop as Art Senave Jewelers, and married Rachel Vandenabeele, also an immigrant, who had arrived here as a 12-year-old in 1912. His first jewelry store ads were written in Flemish, and ran in the local Belgian newspaper, Gazette van Detroit. By 1940, with Detroit’s Belgian population grown to more than 12,000, Art’s mother, Elie, arrived from the old country and took up residence behind the shop. Upstairs, Art and his wife raised two daughters.

Art also raised orchids after building a greenhouse with a motor-operated skylight in the second floor living quarters. During the Depression he earned extra money breeding prize canaries in a rear bedroom. In the basement he built a photographic dark room, which I would use years later as a teenager. When Art bought a movie camera, neighbors nicknamed him Cecil B. DeMille. When one daughter, Mary Lou, aspired to be a classical pianist, Art bought her a baby grand piano and tinkered with its hammers to make it play faster. “Whatever he went into, he went into it with both feet,” recalled Mary Boomsma, who now lives near Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Elie, Art’s mother, died in 1958. Ed Kiska, my father, ran the store for Art while he dealt with the funeral. They became friends. When Art decided to retire, he sold 40 years of his life to my dad. In 1964, with a loan from my mother’s father, Ed bought the business and its inventory for $3,500 (about $27,000 in 2015 dollars) and leased the building, which he bought the next year.

When my father took over, the south side of Mack between Philip and Marlborough featured – east to west, left to right – a gas station, a Chinese restaurant, Edward F. Kiska Jewelers, the Uptown Bar, a bakery, a one-person real estate firm, Tucker’s Barber Shop, and a pharmacy. Tucker’s had four busy chairs and, in the back, a well-curated selection of dirty magazines. We lived in Center Line, a blue-collar suburb. But a year later when our home was appropriated by the city and rezoned commercial, our father’s new business became the family’s new residence. (The Center Line house is now a Rite Aid parking lot.)

My parents slept behind the showroom, in the same quarters where Art Senave’s mother had lived. My sisters, aged 11 and 5, shared one upstairs bedroom. My brothers, 10 and 7, shared the back bedroom off the kitchen and down the hallway from my sisters. I got my own room — a storage closet, actually, but big enough for a bed and the teenaged accessories of the time, including an Alfred E. Neuman poster. I was 13.

The block’s four easternmost storefronts — the Chinese restaurant, our jewelry shop, the bar, and the bakery — were two-story buildings. All four proprietors lived upstairs. Our immediate neighbors were the Louie family, who owned Ming’s Restaurant. “Louie’s Restaurant” had minimal branding power as a place for Lo Mein, so Ah Tuey Louie and his wife, Young Louie, named the place after their oldest son, Ming. The neighborhood knew the couple as George and Mary. I became pals with Ming, Jim, George, and Martin Louie, all of whom would graduate from Cass Technical High School, Detroit’s elite public school.

All the kids on the block hung out in the back alley, and the block became its own support system. The Louies bought their bread from the baker down the street. We got egg rolls from the Louies and brownies from the baker. My five-year-old sister liked to bring our homegrown African violets to Mrs. Louie, and the two developed a bond. My sister also swatted flies in the back alley of the restaurant, and was paid in Neapolitan ice cream. I occasionally shined shoes at the barber shop.

But social cohesion did not reach far. I learned about mid-1960s race relations in Detroit amid a choking vapor of fear, mistrust, ignorance, and misunderstanding. It was all news to an eighth-grader from a small suburb with all of the racial complexity of a North Dakota farm town.

[blocktext align=”right”]All the kids on the block hung out in the back alley, and the block became its own support system…But social cohesion did not reach far. I learned about mid-1960s race relations in Detroit amid a choking vapor of fear, mistrust, ignorance, and misunderstanding.[/blocktext]In 1965, Conner Avenue was the dividing line between blacks and whites in our neighborhood. The Chrysler plant on Conner formed a natural barrier, like a mountain between nations. Black kids seldom ventured across that line for fear of tangling with greasers, guys wearing leather jackets, slicked-back hair and chips on their shoulders. They looked like Fonzie, but some were not that nice. Any black kid riding a bicycle on the wrong side of Conner was assumed to be a bicycle thief and treated as such. White kids stayed on their side of the divide. I was mugged twice, once because I rode my bike over the line and once as I waited for a bus at the corner of Mack and Conner. Despite our geographic proximity, I don’t recall a single African-American classmate at St. Philip Neri Grade School at Charlevoix and Dickerson, only six blocks from the dividing line. Nor do I recall a single African-American classmate in my two years at De La Salle Collegiate High School, now demolished and long since moved to suburban Warren.

The only integration I saw was at Jackson Junior High School, two blocks from our shop. It wasn’t pretty. White kids made fun of black kids because of their thick-and-thin socks and do-rags. Black kids thought white kids were full of themselves and had inexplicable taste in music (Paul Revere & the Raiders versus Motown?). A small percentage of each race disliked the other on general principle. The largest percentage of both races was simply confused and prayed to get through the day. Walking home from school, St. Philip Neri kids traveled northeast on Charlevoix Avenue. Jackson kids walked home in the opposite direction. The white kids from St. Philip Neri were targets. My sister Maureen was surrounded by a gang of girls and roughed up. I was trying to avoid a fourth mugging. My parents insisted bad behavior was not racial, just bad behavior. But you didn’t hear much of that kind of healing dialogue in the neighborhood. Still, my father ended up driving us to school.

Schools and crime – as may have been true with most cases in tens of thousands of families, both black and white – became the deciding factor in the departure of us seven Kiskas. Our parents, who saw what was going on at Jackson, were already paying parochial school tuition for four kids, with another about to enter first grade. It was time to move from the store. We found a home in the inexpensive section of Grosse Pointe Park, only five blocks away. A woman on Maryland Avenue wanted to sell to a large family, contrary to restrictive covenants common at the time in the Grosse Pointes. Our family met her standards. We would attend Grosse Pointe Public schools. Moving day was set for Monday, July 24, 1967.

That day would turn out to be day two of the worst riot in Detroit history. Forty-three people died in five days of sniping, burning, and looting that ended only after the U.S. Army came in with tanks. It began on the west side early Sunday morning and worsened throughout the day. At 4 a.m. Monday, the cops came by and urged my father to lock up the watches and diamonds. And, oh, they mentioned, living above a jewelry store might not be wise at the moment.

Nobody knew whether the rioting would flare up again, or how far Sunday’s high-intensity violence would spread on the east side. The movers called before 8 a.m. asking if the job was still a “go.” My mother said yes because, as she reasoned, she had already taken the sheets off the beds. The kids were instructed to pack the store’s inventory into the family station wagon.

The first east-side call to police dispatch that Monday came in at 9:03 a.m. A gang had gathered at the corner of Iroquois and Harper, five miles away. That would have been about the time we were emptying the store. The movers finished taking our furniture across the line into Grosse Pointe Park and were ordered home by their bosses. By 4 p.m., police aerial intelligence recorded half a dozen east-side fires. By nightfall, our side of Detroit – the city we had evacuated a few hours earlier – was a battleground.

On the first night in our new house, just two blocks from the Detroit city limits, we sat on the front porch and listened to gunfire. On Tuesday night, snipers pinned down firefighters as they tried to knock down a blaze at Mack and St. Jean, a mile and a half away. A 30-year-old firefighter, Carl E. Smith, died in the attack. I’ve often wondered if I heard the shot that killed him. For the next few days we watched Army Airborne troops drive up and down our new street, which was a turnaround point for patrols.

Business at the Mack shop remained fine for a short time after the riot, but my father’s old customers soon began moving farther out. Traffic on the block diminished and deteriorated. We bought a German shepherd and named him Buzzer because his job was to warn of trouble. Shoplifting became more frequent. My father, however, did not decide to move out of Detroit until 1969. An armed junkie persuaded him.

One morning, a customer seemed to ponder whether to buy a diamond or a watch. Instead, he produced a gun and announced he would take everything. My father kept a .38 in the apron of his watch repair bench for such occasions. But this guy had glassy eyes and seemed out of control. Rather than exchange gunfire with a drug addict, my dad handed over the merchandise. Because the neighborhood and the riot had made insurance too costly, he was wiped out. He closed the store and went to work for someone else, but couldn’t stand it, and quit after four days. He briefly reopened the Mack store with help from friendly suppliers, and then a well-connected customer found a new home for Edward F. Kiska Jewelers on Kercheval Avenue in Grosse Pointe Farms. Back on Mack Avenue the second storefront from the left became just another statistic about the exodus of businesses and people from Detroit.

Ah Tuey and Young Chong Louie kept Ming’s Restaurant going for almost three decades after the riot. In 1995 they sold it to a Vietnamese family and moved in above our old storefront. The Louies had traveled a long road to get there.

Both Louies grew up in China. Mrs. Louie’s privileged family became nearly destitute when the Japanese invaded in 1937. All her life she remained fond of canned Vienna sausages, which she first encountered in charity packages from the U.S. Her family’s situation became even more difficult during World War II, and then untenable as the Communists took power. Her future husband, Ah Tuey, had left China in 1936 and settled with his father in Stockton, California.

Ah Tuey fought for the U.S. in World War II. As a veteran, he got help in bringing Young Louie out of China after the war. At first, they tried running a fruit farm in Stockton, California. But they were going broke. In 1962, they moved to Detroit and opened a restaurant. Ming’s was basically a blue-collar diner. Many of the clientele worked at the Dodge Main factory in Hamtramck. Half the orders were for Chinese food, the other half for entrees like meatloaf and hamburgers. “My father went into the restaurant business because he couldn’t get a job elsewhere,” Ming Louie says. “He didn’t end up in the restaurant business because he had an affinity for food. It was the only thing he was allowed to do.”

[blocktext align=”right”]”Here in Detroit, you had a good chance of succeeding if you worked. If you could work, if you could slog, you could get somewhere. It was difficult. But they made enough that the four of us all earned advanced degrees. That never could have happened in Stockton. That certainly would not have happened in China.”[/blocktext]Ming’s served meals from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. Sunday through Thursday, and until 3 a.m. on Friday and Saturday. Prep time meant reporting to work at 5 a.m. The Louie boys worked alongside their parents. Ming waited tables with his mother. Young George backed up his father as cook. Jimmy and Martin washed dishes and bused tables. All six Louies worked seven days. The boys ran the place from midnight to 3 a.m. on weekends so their father could be up at 5 a.m. The kids had to handle the drunks who lurched in after 2 a.m.

I only recall seeing Mr. Louie not attired in his chef’s apron once. He had donned a suit to attend a son’s middle school graduation. His wife, relentlessly upbeat and highly intelligent, ran the cash register and took takeout orders in addition to waiting tables. Most people probably didn’t suspect she had been trained in classical Chinese literature.

Ming Louie believes Detroit provided the family a great opportunity. “There is no way we could have succeeded in Stockton,” he says. “No matter how hard you worked, no matter how many tomatoes you canned, you could never get ahead. Here in Detroit, you had a good chance of succeeding if you worked. If you could work, if you could slog, you could get somewhere. It was difficult. But they made enough that the four of us all earned advanced degrees. That never could have happened in Stockton. That certainly would not have happened in China.”

When the Louis quit the 16-hour days and moved into our old place, they sold the restaurant to a Vietnamese family that tried unsuccessfully to keep it alive. The area had become ever-more dangerous, but it had been their home since 1962. They had friends. They wouldn’t leave. “We tried to talk them into moving out,” Ming says. “They couldn’t believe it was better anywhere else. We’d try to tell them that it wasn’t normal to hear gunfire outside your door at 2 a.m. But they wouldn’t budge. My father would say, ‘It’s better than China’.” In 2007, Mr. Louie fell out of bed and broke his arm. The accident forced the Louies into a suburban senior citizens home.

After they left, the old Kiska shop fell to an irresponsible tenant who later left without telling anyone. Abandoned, the place was ransacked, probably more than once. The end came this spring, on April 4, 2015. An arsonist, as best as can be determined, poured accelerant along the back wall near where Kevin and Damian Kiska once slept. The fire spread, taking out the kitchen. The call came to fire dispatch at 2:20 p.m. A power line went down within minutes. The fire that started in my brothers’ back bedroom reached the crawl space between the roof and the ceiling and surged forward to the Mack Avenue wall, which belched smoke. The fire chief on the scene can be heard on audiotape asking his men inside: “What’s the ceiling look like up there? I don’t want you under that roof for too long.” The answer: “It’s about to catch the Chinese restaurant.” Then: “Chief 6. Everybody inside, come on out.” With the building’s stability in question, the fire had to be extinguished from above.

Neighbors told police they spotted a man running into the alley, so an arson investigation was requested. After the fire the restaurant was classified as a dangerous building; it was demolished in mid-July. My father’s old building will surely be knocked down, too, probably soon. Mrs. Louie died just ten days after the fire. Mr. Louie had died in 2013.

I needed to see the end of this story, which began with an immigrant couple from Belgium, continued with a large family from Center Line, and ended with a hard-working Chinese couple who stuck it out to the end.

The red street door leads onto stairs to our living quarters. It was not locked one day in July when I stopped by with my son, Eric, and a friend, reporter Steve Neavling. Steve seems to enjoy going into abandoned buildings. I wondered about danger and whether I would receive an unpleasant greeting from squatters. “A couple of white guys in the middle of the day in this neighborhood?” he asked. “Most people would think we were DEA agents, insurance adjustors, or realtors.”

I walked up. The floor was three inches deep in random debris. Walls had shed their plaster. Burnt-out rafters had collapsed on the floor. Why was a ketchup bottle still sitting on a shelf? The mess was incomprehensible. This living room was once a place of order and beauty. In the 1940s, Mary Senave practiced here on the baby grand piano Art had bought and adjusted for her. Art’s greenhouse was now a total wreck. I remembered watching the Smothers Brothers TV show here. I thought about the Louies living out their hard-earned retirement here because they thought this was as good as it gets.

We took a few photos of my brothers’ old bedroom, where the fire began, and of the old showroom where I worked with my father, listening to news all day on the radio and discussing world events. I was hopeless as a jeweler, but those hours with my father turned me into a journalist.

As we left, three teenagers walked past and one asked: “Hey, are you guys buying that building?”

“No, I just used to live here,” I said.

The block now sits on the edge of an urban prairie. The only thing left standing in a once-prosperous shopping area is a sign that says: “Parking For Mack-Chalmers Shopping Center.” Still, there is life. Harry’s Barber Shop is two doors down from my father’s old shop. Harry’s thrives. A few decorative plants, tended to perfection, grow in front. Customers come in and out, all ages, men and women. It’s also a neighborhood gathering spot. A sign on the wall says: “Please…No Profanity.”

Curtis Harry owns this barber shop where I once shined shoes. When he bought the place in 1970, he found bullet holes in each of its four chairs. His 45 years in business there, however, make him the longest-tenured entrepreneur in the 14500 block of Mack Avenue, so far as can be known, the latest in a 90-year lineage of shop owners who worked long hours in an effort to succeed. Like the Senaves and the Louies and the Kiskas, Curtis Harry came to Mack Avenue seeking opportunity to prosper. Mr. Harry is 81 years old. As long as he is alive, no one can say the American dream is a myth, even on my old block.

[blocktext align=”right”]Maybe buildings belong to the great circle of life, too: Birth, death, renewal.[/blocktext]Harry came to Detroit from Alabama in 1953 and held two jobs for 25 years, working the midnight shift at a factory and cutting hair day by day. Seventeen of those years involved seven-day weeks. He speaks most proudly about how that work paid off — not for himself, but for his five children. Each has a college degree. One son, Kevin, is an executive producer for Inside Edition. Two are administrators with the Detroit Public Schools. Curtis Harry and the Louies became great friends. “We looked out for each other,” Mr. Harry says. But after the Louies moved from my father’s old building, he said, “people just tore the place up. People just didn’t care.”

Hints of progress exist on Mack in the five blocks between Chalmers and Alter Road, the border with Grosse Pointe Park. There’s a relatively new strip mall at Mack and Alter and the World Outreach East church recently landscaped out front. Curtis Harry is hoping that the old Kiska building will be knocked down soon and replaced by greenery. “I want to make it look good,” he says. He thinks serious rejuvenation will take years. But he is not leaving the block.

The Senaves and the Louies who planted their flag on Mack Avenue are gone. So is my father, who worked 12-hour day after 12-hour day fixing watches and selling jewelry.

The four newcomer families I know best — the Senaves, my own parents, the Chinese-American couple next door, and an African-American family headed by an 81-year-old barber — produced two lawyers, four teachers, two television producers, two Detroit Public Schools administrators, a jeweler, an artist, a medical data analyst, and a tenured university professor.

Maybe buildings belong to the great circle of life, too: Birth, death, renewal. The spirit of the block almost demands it.

___

Tim Kiska is a native Detroiter and a veteran newsman. He wrote for the Detroit Free Press (1970-1987) and the Detroit News (1987-2002) before earning his Ph.D. in history at Wayne State University in 2003. He is currently an associate professor of communication at the University of Michigan-Dearborn.

Belt is a reader-supported publication — become a member, renew your membership, or purchase a book from our store.

What a moving portrait, Tim – rich in detail, it illustrates what a complex issue blight really is.

At the end of the day, it’s about people.

best, -Wendy Case

Tim, I loved this story. Thank you for sharing it. It’s my Dad’s story too–of raising a family in Detroit while working 12-hr days, running a Mobil gas station in River Rouge. It’s the story of heroes.

Tim, I always was a fan of your writing, and this is just another example of why your work is missed. I personally related to the sensibilities in your piece. The address on my birth certificate is on Charles Street, just a few blocks from your homestead. Well, it used to be. I looked it up a few months ago on Google Earth, and it’s an urban prairie today.

When I lived there in the middle Fifties, it was a full-on neighborhood, streets filled with trees and houses, and you could hear the traffic on Jefferson a couple blocks West. Two memories of my pre-school life there endure. I remember being about three years old, and I had a girl-friend across the street with a new wading pool. I was invited to come over and swim, and I was so excited that I bolted from my front yard, sprinted across the street (guaranteed without looking), and I flopped into the little pool. Most of the water was splashed out, my friend started screaming and crying, and I was invited to go back home.

The second event isn’t a memory, except that it has been told by my mother so often that I now may hold faux memories of it. My Dad was a truck driver. One day, without so much as a bye! to my Mom, I enterprised up a small suitcase and set off down the street to “go work with dad.”

Mom caught up with me before I got as far as Jefferson.

I’m just finishing a novel that deals with two suburban Detroit high school kids finding a path back to the summer of 1967 (inspired by King’s “11/22/64.”), where they bring back to the present new collectable muscle cars for fun and profit. I have been struggling with the idea of them playing a role, or having some experiences, related to the Detroit events of July ’67. I think your story just moved me to make their experience more exciting.

Thanks again for the great piece. More, please.

Such a pleasure to read this well written story.

Great piece# Curious: Was this the Wally Koster who became an advertising copywriter?

One in the same. I haven’t had a chance to talk with him in years, and tried to look him up this week–with no luck–that he’s in the story. Please pass this on. He was great.

I have produced a documentary that examines Detroit from a positive perspective it titled “The Great Detroit, It was-It is-It will be” I focus on the good things that have happened and happening and will happen in Detroit.

Its 55 interviewees covering a little of everything with tons of little known facts starting with the beginning at 1701 and ending with the plans for a brighter future.

I did include one abandon building to give the film some balance.

I invite you to check it out on amazon.

I remember the store on Mack. Art Senave was our family jeweler and when he sold the shop to your dad, we stayed with the Kiska’s until the store closed. What a great story you’ve told about your family’s history.

I am privileged to call Tim a good friend & former WWJ radio co-worker. He is that rare combination of a true intellectual who can communicate compellingly with anybody he encounters. I’d heard his story in bits & pieces over the years, but never as an emotional narrative of this power. If you’ve never read any of Tim’s books, do yourself a favor and find them.

I’d like to conclude on an optimistic note: Tim’s experience has been replicated innumerable times over by former Detroiters, but I can see a new Motortown trying to emerge from the debris of the last one.

When I was researching Detroit history for my former WWJ podcasts, I discovered many small, isolated glimpses into the city’s sad future as early as the 1950’s. They only make coherent sense when you know the culmination of the downfall. Now, I look for the same kind of small things, positive ones, and wonder “will people 50-60 years from now regard these little trends and as early harbingers of Detroit’s resurgence?” I am seeing more of them each time I visit.

Thank you Tim. Just wonderful!

Tim– great story. I grew up in northwest Detroit in a similar neighborhood — street after street of post WWII bungalows filled with second-generation Americans. Your stories brought back many wonderful memories of the walkable neighborhood stores, schools, library, park, and comfortable, safe lifestyle. Accepting the fact that I could not safely stay there to raise my own family was sad. I appreciate the stories of rebuilding, renewal and rebirth– it would sure be satisfying to watch another generation return to establish similar neighborhoods. Thanks for your fine story and talent for recording these historical vignettes.

Sharon Walker Rose

Having been born and raised in Detroit, first at 4415 Montclair (now torched) and then at 15870 Ferguson (now torched), I can relate well to the story. It was wonderfully written, and brings back many memories of my family growing up in the Motor City. My Grandfather worked at Chrysler on Conner; we shopped at the Eastern Market and other family grocery stores on the east side. I attended parochial grade schools on both the east and west sides, and high school at Catholic Central. I was a member of the National Guard unit that was activated and patrolled Twelfth Street during the riots.

Detroit is still my home, and I visit it annually. I have hope that the partial resurrection continues to bring some dignity back to a once wonderful home town of mine. Thank you for the wonderful job of describing your family and their experiences in my home town.

Tim,

Unbelievable piece. Absolutely beautiful. In 1964 Ellen and I were living at 3611 Nottingham, just off Mack, nine blocks east of your place. Who knew? You should visit in the Leelanau one summer; we’ll welcome you with open arms.

All the best, Pisor

Tim, this is a wonderful gem of a story (so to speak), and very rare, in that it is totally void of the racial animus that marks most stories about the changes in the city, while explaining the racial dynamics in matter of fact reportage. Your professionalism – and your dear heart – at work.

I have to much to say on this piece, there is so much within; perhaps I will do so on facebook. Suffice it to say that we have much in common – my father, as you know, a record shop owner who ultimately lost his store on 12th in’67.

I am hopeful that the truthful telling of our stories – like this one – will disengage us from the bondage of the false narratives and tropes that tend to dominate discourse on Detroit, and the sweet and painful truths, such as you have recounted, will free us to build a really new Detroit.

I am interested in the History of Detroit. I don’t have any Gritty Urban Tales of my Own. We moved to Southfield from the Cleveland Suburbs in ’64. My Late Father worked at Ford Research in Dearborn, and my Late ex-musician Mother drove me to the Music Institute on Kirby for Piano and, later, Violin lessons. When the ’67 Riots hit, we were in Montreal at Expo ’67 with my Dad’s Family. We watched on the TV News Night after Night, pictures of the Chaos on Twelfth Street. I don’t remember what Detroit looked like when we came back across the Windsor Tunnel, but my Mother said years later that there was a lot of burned out stuff on Grand River (there WAS.) I took swimming lessons and tragicomic Sports Skill Camp at the Jewish Community Center when it was located on Meyer and Curtis in the City. By the early Seventies they moved out to West Bloomfield. Ironically, I rotated at a Detroit Hospital as a Medical Student that had previously been a JCC-near Dexter and Davison. I still live in Southfield. I moved back into my Childhood home to take care of Father in his Later Years.

Hey Tim ,wonderful story. I came across this while searching for the name of that fantastic bakery across the street from St. Philips. That place gave me a sweet tooth for life. I’ve never found another bakery with such quality, freshness, (straight out of the vat) and endless variety. Your choice of over 30 kinds, only a nickel apiece!

By the way, wasn’t Carmen’s Pizza in the same block as yours?

Thanks for sharing the memories.