Hundreds of angry miners crowded around the machine, several attacking it with hammers and axes. Finally, fifteen sticks of dynamite were placed under the motor, and a firing wire and exploders attached. A few minutes later there was a terrific blast and the shovel was reduced to a tangled mass of wreckage.

By Mitch Troutman

Excerpted from The Bootleg Coal Rebellion: The Pennsylvania Miners Who Seized an Industry, 1925-1935 by Mitch Troutman published August 2022 by PM Press.

“It’s anger . . . that’s what it is. You know when you’re about to get fightin’, crazy mad, you get a hot, sick, weak feelin’ in your guts? Well, that’s what it is. Only it ain’t just in one man. . . . Ever’ place I go, it’s like water just before it gets to boilin’.”

—John Steinbeck, In Dubious Battle.

Father P.J. Dougherty left mass one Sunday and headed to the radio station. The priest of St. Kieran’s Parish, he was the most prominent representative of the four thousand or so people of the Heckscherville Valley, the stronghold of the Molly Maguires sixty years earlier. His parishioners and others sat around their wood-framed family radios, waiting for Dougherty to begin his address. They did not get what they expected.

“I am sorry to inform you,” he spoke, “that I am not permitted to broadcast the address I have written. The reason for this is that an official of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal & Iron Company has threatened legal proceedings against the broadcast company.” He asked the listeners to gather in person the following night.

The Pottsville Journal, the largest newspaper in the county, was not so intimidated. The following day, it ran the full text of the Father’s censored speech.

“I represent the down-trodden people of Schuylkill County, and am trying by the agency of my voice and my pen to liberate the poor thereof from the heel of the coal trust companies.” Not only had Reading Anthracite closed the last collieries in the valley, but they had now issued orders to flood the Pine Knot colliery, despite locals having found companies willing to buy or lease the mine. Father Dougherty refuted the company’s claim that there was no demand for coal, saying, “Yet we have gone out and procured sales which they refused to handle.” By “we,” he needn’t say bootleggers, for everyone already knew.

Three thousand people packed into a mass meeting the next Sunday—or tried to, because there was no room for a third of them, who instead listened via amplifiers on the rainy street. Local politicians, doctors, and clergy presided over the meeting, which called for the state and federal governments to force Reading Anthracite to lease the grounds. As had happened in other towns, the meeting elected a committee to speak with Governor Pinchot. The committee got no further than those in Minersville or Trevorton had. What leverage did little Heckscherville or even Governor Pinchot have to force a reopening?

Before the month was out, events came to a head. The same Heckscherville miners in pews and mass meetings by day were loading bootleg coal trucks by night. When the state refused to lend police to Reading, company police seized the bootleggers’ coal and blockaded their road, which ran through the Pine Knot strippings, stranding several coal trucks. In response, five hundred people blockade the strippings itself. It’s unclear who dynamited the access road—each group blamed the other—but afterward the company relented.

Reading Anthracite’s president was A.J. Maloney. Based in Philadelphia, he saw little reason to meet with delegates from closed collieries. After all, Reading Anthracite had presumably made the most economical decision and the now abandoned towns had nothing to offer the company. According to law, Reading owed them nothing.

Rumors swirled around Christmas 1933 that Reading was planning to flood five closed collieries surrounding Shamokin and open a large strip mine. The Shamokin News-Dispatch, the largest newspaper in the area, demanded an official statement. Receiving none, editor Joseph Agor called Shamokin’s bankers and businessmen to support the miners in a bold editorial titled “Fight, Shamokin!”

The President of the United States has indicated in no uncertain terms that the people of the nation are more important than any consideration of profits could ever be. He has fought for the preservation of industry as a means of aiding the people, after industrial leaders plainly showed they are incapable of managing their own affairs. The Governor of this state has also repeatedly declared that the people are of far greater importance than combines and corporations.

Groups like the American Legion, the Moose Lodge, and the Rotary passed resolutions. Banks, businessmen, and clergy wired the White House to intervene. The town’s middle class organized a “save the mines committee.” None of this, however, earned A.J. Maloney’s attention.

One of those five mines was the Henry Clay, whose 750 miners had been out of work for two years but still maintained their UMW local. In the fall of 1934, they came up with a strategy that proved to be more effective than anything else the region had tried. Local president Joseph Whalen called a mass meeting, where the miners publicly decided that they and anyone who wished to join them would “land rush” the Henry Clay grounds in one week. Once there, they would “stake out claims” for bootleg holes.

Within three days, Whalen and other local leaders sat in a Philadelphia board room with Maloney. The miners had found their leverage in the economic threat to the company property. They postponed the land rush during negotiations, though many of the miners were likely digging on Reading grounds already.

By Hook or By Crook

The coal holes of Mahanoy Plane lay beyond a strip mine, which the bootleg coal trucks had to cross to access the highway. When the company blockaded the access road, 150 bootleg miners and another 300 friends and family immediately picketed the remaining roads to the strip mine. In solidarity, the company workers shut off their machinery and joined the picket. A contingent then marched on the colliery that processed the coal and called out another 450 workers. The immense display of solidarity pushed the company to negotiate quickly. The colliery and strip mine reopened the next day; under the agreement that bootleg truckers could only use the road when the strippings was not blasting. As Clarence “Mooch” Kashner explained:

Like I says, when they harassed us in any way shape or form, we would try to reciprocate, okay? We went around already shutting union jobs down, and they shut down. Of course, they didn’t like to shut down, but they did just in sympathy, and they knew it. They probably had somebody in their family working a bootleg hole, you know. You don’t know.

Nothing galvanized the miners to collective action more than the dynamiting of coal holes, however. For several days, an escort of fifteen state police joined Coal & Iron Police while they blasted hundreds of coal holes. They had destroyed ten in the village of Mary D, when they were surrounded by a large crowd that booed, forcing the police to retreat. The colliery boss offered to open a strippings to employ some of the bootleg miners. In response, the miners held a series of meetings that drew as many as a thousand people. Dubbing themselves the Self-Employed League, they declared their opposition to any Mary D strip mine. A local Republican judge attended the meetings in support, as did James Gildea, who served as their negotiator with the company. The bootleggers’ group voted to send the local politicians to Harrisburg with a request that Pinchot withdraw the state police.

Only days later, a thousand people from various towns of the “West End” surrounded a cohort of state and private police in Branchdale, driving them off. Several followed them in coal trucks all the way to Reading headquarters in Pottsville, after which they held a parade. Many local politicians attended their large meeting in support. They also appointed miners from both regions to go to Harrisburg and talk with the governor. Pinchot ultimately agreed to restrain state police in blasting cases.

The scenario played out in Mahanoy City as well. The bootleggers threatened to put out the fires in the colliery boiler, stopping work. Gildea—by this point a congressman-elect—was on hand and urged them to get more organized if they wanted to take on the companies. They dovetailed this meeting with one on price-setting, trying to fight back against the encroachment of the coal breakers.

Ira Cochran, head of the NRA code-writing process, fumed that the situation of the Anthracite “has become so serious as to amount to rebellion and civil war, which only the calling out of the National Guard can suppress.” As far as Governor Pinchot was concerned, though, there was only one solution to bootlegging, and it was out of his hands. He repeatedly told the companies and the press that the coal companies “can at any time put an end to the production of bootleg coal by reemploying the men who are producing it.” It’s not that he was apathetic. Rather, he had a long history with the miners and the “hard-boiled monopolists,” as he called them during the strike of 1925. He had no desire to intervene and protect their monopoly by punishing working people. As a politician, who by nature always aspire to higher office, he likely also saw a problem he couldn’t solve and didn’t want his name tied to it, especially with less than a year remaining in his term. He may also have shared the opinion expressed by the Baltimore Sun-Times: “Yet the little that a company loses is well repaid by the lack of that unrest which is to be expected in a district where the wage earners, a large percentage of whom are foreign-born, were ‘laid off’ from well-paying jobs three or more years ago.”

So when the bootleggers formally petitioned him, Pinchot agreed to halt state police involvement in dynamiting unless there was rioting—a radical move, perhaps, but these were unprecedented times. It was a signal victory for the miners and in many ways a reward for their discipline in the strikes of 1923 and 1925.

By Christmas 1934, collective actions had led to the creation of at least twelve separate bootleggers’ associations in every corner of the Lower Region. In addition to settling the conflicts that birthed them, their unity emboldened them and allowed for a better coordinated movement. Rather than plea bargains in court, they encouraged all bootleggers to plead not guilty and jam the court system. They consolidated key cases for which the union hired lawyers. The bootleg unions collected dues to cover legal fees, as well as death benefits for widows.

Inevitably, something as large as bootleg mining was bound to be organized by someone. The term “bootleg” was primarily used for liquor during Prohibition—which was only repealed in 1933. The American mafias rose to power by seizing control—and regulating—the booming black market for liquor. Through violence they skimmed profits, but they also made it profitable by limiting competition among producers, transporters, and retailers. Through their consolidated power, they influenced politicians and police to ensure only a minimum of liquor bootleggers were arrested—often those who were out of their favor. They expanded that control into drugs, prostitution, money laundering, and extortion.

Bootleg mining was frequently accused by opponents of being controlled by racketeers. So why didn’t the mafia control it? According to Joe Agor, “There is no easy money in coal bootlegging for the parasitical racketeer, and if there was God help the racketeer who tried to collect it.”

Bootleg coal could not continue to exist as thousands of competing producers, and if one party didn’t take control, another would.

Instead, the bootleggers’ unions organized the trade. There was no money being taken off the top, unless you counted breakers. The unions stabilized prices and handled disputes. Its power came not from “protection” or payoffs but in numbers and solidarity.

The unions collected dues money and reinvested into the movement, in the form of death benefits, lawyer’s fees, and gas money lobbyists. Most bootleg leaders took no money for themselves except travel costs. There were one or two swindlers who made off with the war chest, never to be seen again, but this only destroyed the bootleggers’ faith in those individuals, not in their method of organization as a whole.

Forming unions was the most radical and militant bootlegger action of them all. They negotiated with companies and politicians and could take clear positions, including their central demand: reopen the collieries. Only then would they abandon the coal holes. The organized bootleggers also demanded a new level of respect from the press, which they insisted call them “independent miners” rather than “bootleggers.”

The organizations were fluid, with no set names (they were slightly altered every time they were published). Among the people, they were all simply known as the “bootleggers’ union.” It wasn’t a “true” union, because they weren’t employees and had no boss to negotiate with, but if there’s one thing miners know, it’s the union, and so that’s what the bootleggers were. They identified with the “brotherhood” aspect of the union, and even as the bootleg trade grew more complex, the bootleggers saw each other as equals and moved forward that way. They did not want to compete with each other—and hardly even thought to do so. Just like miners put their lives in each other’s hands, the bootleggers were determined to survive together, or not at all.

Weekly meetings held at fire companies or union halls got raucous. William H. Adam was secretary of a bootleg union in Schuylkill County. He describes how meetings tended to go:

There were meetin’s with as high as five, six hundred a meeting, maybe more; and, of course, it seemed that mob rule was always the main swing of the thing. When somethin’ didn’t suit somebody, well, of course, he’d just stir up a little fussin’, and, of course, the next thing there was a mob there. And that would take care of it.

They were heavily democratic, not only in the sense of voting, but also because they were engaged. Most leaders had very short terms, because of active democracy, not official term limits. Little was truly official. Presiding over hundreds of emotional bootleg miners was not an easy job, and for that reason the bootleggers tended to favor electing leaders who were respected by all and who were strong enough to facilitate angry crowds.

Edgewood

As so many conflicts played out, the Henry Clay miners continued their negotiations with A.J. Maloney. The Reading president could come across as very sympathetic and agreeable in person, and he used his charisma to stall out the miners. He floated lukewarm proposals and suggested he would reopen the colliery if the UMW local could prove there was demand for their coal. The miners launched a survey of the Baltimore and Philadelphia markets, with the help of the truckers, and actually made a pretty good case but, ultimately, got nothing from Maloney.

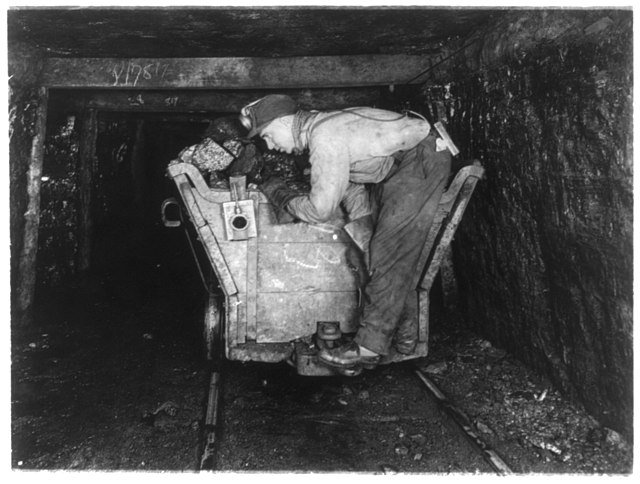

Just as talks petered out, the Stevens Coal Company (a Reading lessee) happened to move a large steam shovel to the massive Shamokin Edgewood tract. Until this point, bootleg miners throughout the region focused on mining small, steep coal veins that were unprofitable for companies to mine. Edgewood was the exception. Agor’s News-Dispatch described the tract: “Estimates of the number of men employed in the mine holes on the Edgewood tract vary. All the miners interviewed agreed that the number is at least one thousand. Some of the men think that at least fifteen hundred are at work.” Those numbers are unlikely, but it was certainly over five hundred. One miner told the newspaper, “No market for Shamokin coal! Hells bells, we can’t mine enough. There’s more coal going out of these holes than could be taken from a good-sized mine, yet the truckers are yelling for more.”

The description of the tract is incredible. “Shaft towers rear above the trees in an endless row. Most of them are built from untrimmed timber, pieced together and braced in a more or less primitive fashion. They shake as the improvised ‘buckets’ come to the surface, but they stand for all that.” The men built improvised fans—some from wooden planks on a car engine—and linked the mines underground for ventilation. “Vent pipes from the fans to underground present a variety of rain spouting, stove pipe, rubber hose, and old automobile tire tubes.” The miners had committees that settled disputes and collectively hired a night watchman; they even had their own mine inspector! Each coal hole was checked weekly.

Stevens announced it would strip the tract and destroy the bootleg mines. The company said that once stripping was done, it would open an underground mine on the property and reemploy hundreds. The bootleggers believed that to be far-fetched. Stevens tried to bring in the power shovel the next morning, but bootleggers poured out of the mountain and surrounded the shovel before it entered the woods, forcing the company to move it back into town. Both sides regrouped. The shovel returned to the tree line along with Stevens’s Superintendent George Jones and a state trooper, but the bootleggers had built a blockade of fallen trees, rocks, and rubble. Again, the shovel retreated, but this time the miners followed.

According to the shovel operator, one bootlegger asked him, “Do you stand to lose anything if something happens to that shovel?” He did; he was a subcontractor who owned the shovel. Then they asked, “Is it insured?” The operator said it was. “All right then. Get your men out of the way. We’re going to blow that shovel to hell.”

Hundreds of angry miners crowded around the machine, several attacking it with hammers and axes. Finally, fifteen sticks of dynamite were placed under the motor, and a firing wire and exploders attached. A few minutes later there was a terrific blast and the shovel was reduced to a tangled mass of wreckage.

And then . . . nothing. Reportedly two thousand people were at the scene when the dynamite went off that December afternoon. The mangled corpse of the shovel sat as a monument in Edgewood for some time, the few functional parts salvaged by its owners. Stevens Coal Company had little response. This must have driven them mad, but they recognized that there were thousands of men out there with dynamite, and Stevens had much more to lose than a subcontracted steam shovel.

The winter of 1934 started out quite warm, and what would have been a series of blizzards was instead a terrible downpour of rain. The next few weeks left the Edgewood coal holes flooded, halting all work. Six bootleg miners made their way to Superintendent Jones’s office at Stevens Coal. Would he mind, they asked, loaning them a water pump to clear their mines?

Mitch Troutman is a writer, educator, organizer, and jack-of-all-trades living in Central Pennsylvania. He is a direct descendent of bootleg coal miners and belongs to the group Anthracite Unite.