An upcoming art show asks of Braddock, Pennsylvania, ‘Where do we think this is going?’

By Nathan van Patter, PublicSource

In 2018, my wife and I bought our first house in North Braddock. Early after moving here, I started to paint almost exclusively paintings about the 15104 ZIP code, which turned into an obsessive three-year project and a coming gallery show.

We talk about the Rust Belt in terms of an unsuccessful and inextricable link to a fading past. However, places like North Braddock will continue to exist, even as places like Oakland start piloting flying cars. No amount of not noticing struggling neighborhoods will make them disappear. North Braddock and the Mon Valley were the technological future—until they weren’t. I wanted to ask a question: Where do we think this is going?

I found out about Unsmoke Systems Artspace through a friend, and pitched doing a hyper local series of paintings and sculptures. Though I continued to work a forty-hour-a-week job, I painted through the isolated nights of the COVID pandemic and was able to put substantial time into the show. I began my usual process, half painting and half sculpting with wood chips, plumbers glue, glass and caulking. Some of the wood I bought, but much of the wood was carved with an adze from a pine log I got off Craigslist.

I made a series of spaceship paintings based on the buildings in Braddock and North Braddock to ask the question: Where do we see areas like mine in our science fiction future?

Space Station 15104

The tension between surreal spaceships and the old, often brick buildings that constitute them give a space for wondering how it would actually look if the Rust Belt went to space.

Braddock Starship #2

The spaceships were just one outgrowth of the life the overall show took on in my head.

I was fascinated by the way that you could walk back past North Braddock’s urban decay and end up in what felt like overgrown forest. A solid chunk of North Braddock’s houses are uninhabited, and some are so decimated that it feels as though they’ve been reclaimed by nature.

Braddock House Painting #6

I started building a base for the art show with one of the starkest visual tensions available: the natural world growing into the local urban decay and weirdly melding with the houses.

Braddock House Painting #5

From there, I began to experiment with language. Could I turn the world I was thinking about not just into a series of paintings, but a language with which I could communicate? I had built the houses out of straight pieces of wood to give them a feeling of being constructed and I had developed a more organic feel for the trees from thinner, more curved pieces of wood combined with wood chips and caulking. What I wanted to see if I could pull of is taking those textures and do a direct transfer to more imaginary pieces. Use cut wood pieces as literal bricks, caulking as greenery, and wood strips as beat up trees and put them on something that wasn’t a landscape.

To find out if this could work, I made one of the strangest paintings of the show. Calling him “King Fear,” I constructed a multilayered analogy in which a monster based on Jungian and Christian religious concepts is eating a chess set.

King Fear

The viewer is on the side of the board that has made the opening move. The monster was constructed in the same style and with the same motifs as my house paintings, in the hope that people would see the houses and feel confident interpreting the much more surreal chess monster.

Similarly, I made two sculptures of cars that are challenged by the same overgrowth and urban distress that binds together the house paintings and King Fear. The first, “Community/Police” depicts how some of the challenges of public safety are tied to the overgrowth and shrinking population in the area.

Community/Police

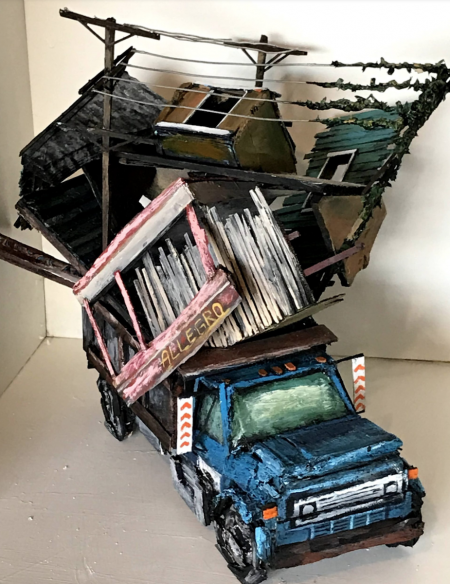

In the second, “Moving Day”, I piled up debris and detritus to an absurd scale on the back of a pickup truck modeled after the one parked catty-corner to our house. I wonder how people picture what needs to happen in a community grappling with this scale of decay.

Moving Day 15104

To counterbalance the darkness, I started doing portraits of important actors in the neighborhood.

Steve

I painted my council woman, Lisa, who is working to help the neighborhood revitalize. I painted Steve who was, through his informal Facebook group, the closest thing the area had to a news agency. Weekly, there would be things that happened in North Braddock which wouldn’t register a blip on any of the local news sites, but had a lot of local importance. Steve somehow manages to keep people in the neighborhood informed and provide details that other places don’t catch.

Lisa

I moved here and I paint about this place because I think the human drama playing just below the surface is more universal than most people realize. The idea of community, abstract in many of the circles of which I’ve been part, is of vital importance in a neighborhood at a critical turning point. A group of people bound together by blight is very different from me and my college friends getting dinner together once a week.

I want people to see these paintings and come to grips with the fragility and hope of our twenty-first century American life. Where will we all be when our broken down buildings are blasting through space? What monsters created through our mass fears do we face down every day as red individuals? In the face of the intractable invasive plants we’ve sown, how do we find a space for the more delicate and strange indigenous environment?

My hope is to compellingly present how vivid and vital-but-struggling areas like mine really are. North Braddock is worthwhile. Please come and see. ■

Nathan Van Patter’s show, “Bound by Blight”, opens on August 6 at UnSmoke Systems Artspace, 1137 Braddock Ave., in Braddock, Pennsyovania. For more information, see his website, Nathanvanpatter.com, or check him out on Instagram @NathanVP_art.

PublicSource is a nonprofit media organization delivering local journalism in the Pittsburgh region at publicsource.org. You can sign up for their newsletters at publicsource.org/newsletters.

Nathan Van Patter is an artist in Braddock, Pennsylvania.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.