You can put your finger on a map and trace it down the Ohio River. From Steubenville to Paducah, it’s nearly a thousand miles, an artery pumping through the heart of America.

By Jeffrey Webb

On a floodwall in Point Pleasant, West Virginia, Cornstalk stands tall. A mob of white men have him cornered, their rifles inches from his face, yet the Shawnee chief is unflinching. His arms are crossed, his back straight, and his gaze level. Painted by artist Robert Dafford, the image depicts the final moments of Cornstalk’s life when, in 1777 at the nearby Fort Randolph, he was taken hostage and gunned down, unarmed, alongside his son.

Dafford, a Louisiana native, was unfamiliar with Cornstalk when he was commissioned in 2005 to paint a series of murals along the floodwall at Point Pleasant Riverfront Park. The murals are an illustrated history of the town. One mural shows a young George Washington surveying the land. In another, frontiersman Daniel Boone is depicted. A massive battle scene recreates the 1774 Battle of Point Pleasant, when Native American forces led by Cornstalk faced an army of Virginians led by Andrew Lewis. And then there’s a quiet scene, a Shawnee village before the bloodshed, before the white man arrived. A family shucks corn. Others build a wigwam. The West Virginia hills stretch across the background, peaceful and still.

Dafford recalled meeting a local resident, a descendent of someone who fought on the Virginian side in the Battle of Point Pleasant. Before the first brushstroke was made, this local provided Dafford with a collection of resources to help the artist learn more about the history of the town. To Dafford, the history felt a little one-sided.

“I went to the state archives,” Dafford said. “I got some alternative information there, information about the Native Americans.”

Dafford drew on everything he learned about Point Pleasant and its people to create the murals, to tell their story. He didn’t whitewash the history. Throughout the Ohio River Valley, he has repeated this process for several towns, towns that were once thriving industrial centers but are now typically seen as little more than the epicenter of America’s opioid epidemic. In many of these places, the murals have jumpstarted economic development and revitalization.

For Dafford, public art can elevate a community. It can give hope to the hopeless.

“These murals,” Dafford said, “establish pride instead of shame.”

#

As a young man, in the 1970s, Dafford served aboard the USS Independence. Cruising through the Mediterranean, whenever he got shore leave he found himself heading straight for the port city’s old town.

“In Europe, every town’s got an old town,” Dafford said. “In the Navy, we’d go explore, and I’d go to the old town. I’d learn their culture. What music they listened to, what food they ate, what their wine tasted like.”

This cultural immersion is something that stuck with Dafford and is evident in his art today. “I got to be good at going into a town and learning about who they are,” he said. At times, his methodologies are more akin to that of an anthropologist than an artist. He spends months at a time in a town. He talks to people – local historians, reenactors, businesspeople, representatives from town government. He scours books and photographs and old postcards for historical details, verifies everything for a given time period, from the style of brick to the style of shoe.

In 1977, in Dafford’s hometown of Lafayette, LA, he was commissioned for a series of works showing the Acadian exile from Nova Scotia. This exile saw the Acadians–more generally known as Cajuns–eventually resettling in the Louisiana bayou. The Acadian paintings brought Dafford international acclaim. He was invited to Vancouver Island for a murals project, where he learned how to make public art and how to incorporate art into a city. This led to a commission, in the late 1980s, from the city of Steubenville, Ohio, to paint murals on buildings throughout their town. This caught the attention of folks in Portsmouth, who then invited Dafford to do something about the floodwall that had protected Portsmouth from the Ohio’s waters since 1943.

“It was like a prison,” Dafford said, describing his initial thoughts upon seeing the massive, twenty-foot high wall. “It was like you were trapped in some medieval walled city.”

That was 1992. Thirty years later and 2,000 years of history is painted on over 2,000 feet of that floodwall. “It’s the largest piece of continuous artwork by one artist in the world,” said Butch Stall, a board member of the nonprofit Portsmouth Murals, Inc., which provides funding for the murals through grant writing and fundraising efforts. “That’s what I tell people. No one’s disputed it yet.”

#

Stall has lived in Portsmouth his entire life. When he looks at the floodwall murals, he sees his home. “Each one,” he said, “is relevant to me. It started out as artwork but now it represents the legacy and history of our area. It looks like a national monument.”

The Portsmouth murals take visitors on a journey from prehistory to modern day, from the burial mounds of the Adena to the Civil War to the shoe factories and steel mills that once breathed life into the city. There’s a mural honoring Branch Rickey, the general manager who signed Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers and a native of the Portsmouth area. Roy Rogers and Jim Thorpe are on the wall. Tecumseh is on the wall.

In addition to the big historical scenes and figures on the wall, there’s also the more mundane – bicyclists, streetcar motormen, a Greyhound bus station, police officers and firefighters, a mural honoring labor unions. The railroad is depicted, as are the city’s medical and educational institutions.

The bulk of the Portsmouth murals were painted within a ten-year span. To this day, Dafford regularly returns to paint new murals and perform maintenance on old ones. In the early days, he sometimes worked with as many as ten assistants on a project; now, with the workload a little lighter, maybe but one or two. A 2013 documentary, Beyond These Walls: Building Community through Public Art, provides a glimpse into Dafford’s work in Portsmouth, showing how the artist puts in hours from sun-up to sundown and how bad weather is always a looming threat. The documentary shows how Dafford–more for convenience than for perfectionism–uses an overhead projector to project a historical image onto the wall, allowing his artists and himself to quickly trace the image rather than losing precious hours recreating it by freehand. Many of the murals have a three-dimensional effect, as if you can walk right into them and take a step back in time.

“People would take lawn chairs down and watch him paint,” Stall said, remembering the community’s early enthusiasm for the murals. “They were literally watching paint dry.”

#

“One of the most important things is that it is art of a higher quality,” Dafford said. “It’s about them. All of them. These are people who’ve never seen themselves in a large, formal way like this, as something to be admired and respected. They bring their friends and relatives to see it. Of course, what they’re really doing is bringing them to see themselves.”

In Portsmouth, school groups visit the murals, sometimes coming from miles away. Tourists stop and visit. They see the murals, but then they see all the other attractions that have either popped up or picked up business since the project began. To name a few – the Southern Ohio Museum and Cultural Center, Candyland Children’s Museum, Market Street Cafe, Patties & Pints. The Haskins House, which opened in 2014, deserves a special mention. Part record store and part art gallery, it demonstrates one of the key goals Dafford said his work achieves.

“With the murals, people get the message that they’re important, they matter, they’re someone worth knowing and worth seeing,” Dafford said. “It leads to the eventual realization that buying art is a good idea. Artists are then encouraged to make art, and others are encouraged to buy.”

#

Just as Steubenville put Dafford on Portsmouth’s radar, Portsmouth put Dafford on Paducah’s radar. Located in western Kentucky at the confluence of the Ohio and Tennessee rivers, with a population around 25,000 people, Paducah launched its own floodwall murals project in 1996 with Dafford at the helm. Years later and the murals now span the length of three downtown blocks. The most recent panels were unveiled on September 2.

“You can see them from a long distance away in town,” said Ro Morse, the executive director of Paducah Wall to Wall. “You get pulled toward the waterfront.”

Paducah Wall to Wall is an all-volunteer organization that oversees the murals project. They solicit private citizens to sponsor specific panels. The city pitches in to maintain lighting and lawncare, but much of this cost is offset by Paducah Wall to Wall’s sale of souvenirs like t-shirts, prints, and postcards. In 2020, they published a book, Paducah Wall to Wall: Portraits of Our Past, with proceeds benefiting maintenance costs. “It has been a tremendous partnership of public and private resources,” Morse said.

That’s not to say the work was easy. The Paducah floodwall faces west, where the sun is high. Morse called it “a wind tunnel.” It’s “not optimal conditions,” she said. Nonetheless, Dafford committed himself to the project, building layer upon layer of paint to withstand the elements. “That’s longevity,” Morse said.

This past June, Dafford had some extra help with his work. He partnered with the Paducah School of Art & Design to lead a twelve-day murals master workshop, the first time in his career that he’s undertaken such an endeavor. Nine students from states all across the country came to Paducah to learn from Dafford. Some students returned after the workshop’s conclusion to continue working with him.

Paducah, like Portsmouth, has seen a boon in tourism thanks to the wall.

“You can go down to the murals at any decent hour and see people looking at them, people from all over the world,” Morse said. “If you worked in the telephone industry, river industry, for a fire department, in strawberry fields, if you ride a Harley-Davidson, if you work in a hospital–-it doesn’t matter who you are or where you live, along that riverfront there is going to be something you identify with.”

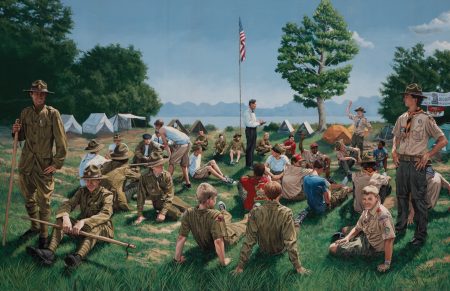

For Morse, her favorite mural is of Paducah’s Boy Scout Troop 1, which shows a group of young scouts gathered together at a campsite for evening roll call. Their uniforms and tents reflect the changes seen in the Boy Scout’s first hundred years of existence, from 1910 to 2010. Some boys are dressed like World War I doughboys with wide-brimmed hats while others sport shorts and t-shirts.

“The way he can pull a hundred years of history together in one 14×20-foot image is phenomenal,” Morse said. “It’s just special.”

#

You can put your finger on a map and trace it down the Ohio River. From Steubenville to Paducah, it’s nearly a thousand miles, an artery pumping through the heart of America. Your finger passes over Covington, KY, where Dafford painted eighteen murals detailing their history, including a scene of Peggy Garner and her family crossing the Ohio in the winter of 1856 to escape the slaveholding south. In the painting, Peggy holds her two-year-old daughter close to her chest. As the story goes, when the family faced recapture, she killed her daughter to spare her a life of slavery. Continue tracing and your finger passes over Maysville, KY, where Dafford painted murals honoring the Marquis de Lafayette, the Underground Railroad, and Rosemary Clooney. It passes over Jeffersonville, Indiana, with its murals by Dafford, and it passes over Point Pleasant, where Cornstalk stands tall.

Point Pleasant has seen better days. In 2018, the Point Pleasant River Museum was destroyed in a fire and has yet to be reopened. The annual Mothman Festival, one of the town’s biggest tourist attractions, was canceled for two years in a row due to COVID concerns. County HIV cases, likely attributable to drug use, rose in 2021.

The town’s floodwall murals have not gotten by unscathed. Aging, weathering, and air pollution have darkened them a bit.

“I’m going back there,” Dafford said. “I’ve got to repaint the skies.”

Jeffrey Webb holds an MFA in creative writing from West Virginia Wesleyan College and has written nonfiction for a variety of websites and publications, including JSTOR Daily, Learning for Justice (formerly known as Teaching Tolerance), and Appalachian History.