By Lauren Sieben

On a Saturday morning in early February, with six inches of snow covering the ground and temperatures hovering around 20 degrees, a group of 25 adults in puffer jackets piles into a yellow school bus for a tour of Milwaukee.

Instead of buzzing through breweries or stopping to admire Cream City architecture, the driver follows a route through Milwaukee’s once-redlined neighborhoods — the parts of the city that banks and insurance companies refused to serve on the basis of race until the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed the practice.

“There are parts of the city that people never go to. They hear about them on the news, but they don’t really hear why those neighborhoods became what they became.”

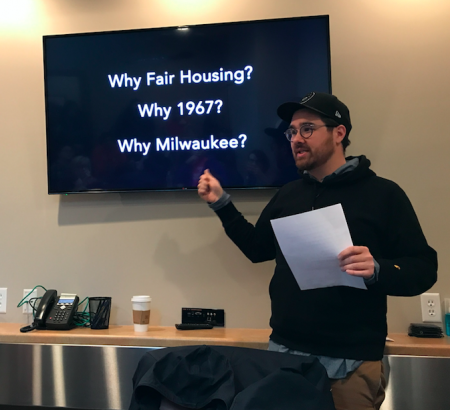

Before hopping on the bus, our group meets in the conference room of Town Bank in the southside Walker’s Point neighborhood. Adam Carr, one of our two tour guides, connects his laptop to a screen and begins clicking through a brief presentation. One slide displays the Wikipedia definition of redlining — ”the practice of denying services, either directly or through selectively raising prices, to residents of certain areas based on the racial or ethnic composition of those areas.” Several slides show black-and-white photos of Milwaukee’s historically black neighborhoods from the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, depicting bustling main streets and thriving storefronts.

Joaquin Altoro, Carr’s co-guide for this specific tour and a vice president of commercial banking at Town Bank, shares a quick disclaimer (the opinions expressed on the tour don’t reflect the opinions of his employer), before pointing to his shirt, which says, “Milwaukee?”

“I love that shirt,” Carr says from behind his laptop. “For me as a Milwaukeean who loves Milwaukee, that is the shirt that best represents how I feel about it. I feel a lot of ‘Milwaukee exclamation mark,’ but I also feel a lot of ‘Milwaukee ellipses,’ a lot of ‘Milwaukee, goddamn,’ you know?”

Carr then shares a paraphrased version of the James Baldwin quote: “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

* * *

The redlining bus tour is part of a series Carr calls Milwaukee Tours for Milwaukeeans, which endeavors to give Milwaukeeans a deeper understanding of their city. A lifelong Milwaukeean himself, Carr got the idea during a stint producing radio segments about Milwaukee neighborhoods.

Adam Carr [credit: Lauren Sieben]

But while Carr spent most of his time in the field with people from across the city, he worried that his work might make some listeners complacent.

“Ideally, a story would compel someone to cultivate their curiosity and see something for themselves,” says Carr. “But I was worried I was reinforcing people across divisions by making them feel content in their understanding of a place they haven’t been to.”

Carr is not the only local using interactive tours as a means for educating Milwaukeeans about their city.

Reggie Jackson, head griot (docent) of America’s Black Holocaust Museum, located in Milwaukee, offers “segregation tours” that focus on the intersection between segregation and the loss of Milwaukee’s manufacturing jobs starting in the 1960s, which led to many of the abandoned, boarded-up factories and homes still sitting vacant today.

“I read something years ago about ‘ghetto tours’ where they’d invite whites, generally, to go to so-called dangerous parts of the city to show what it looked like but with no historical context.”

“There are parts of the city that people never go to. They hear about them on the news, but they don’t really hear why those neighborhoods became what they became,” says Jackson. “The assumption in many cases is that black people didn’t take care of their properties, but people tend not to make the connection to the huge loss of manufacturing jobs.”

Jackson considers himself a “public historian” — by helping locals better understand history, he hopes they gain a deeper understanding of modern segregation that isn’t rooted in stereotypes. The risk, says Jackson, if you’re not careful about offering historical context, is that these types of tours devolve into poverty tourism.

“I read something years ago about ‘ghetto tours’ where they’d invite whites, generally, to go to so-called dangerous parts of the city to show what it looked like but with no historical context,” says Jackson. “It was like when people see a car accident, they slow down to look to see if there’s a body on the ground.”

* * *

When the bus leaves Town Bank, we drive along Walnut Street through the Bronzeville Business District for an “after” view of the black-and-white “before” photos we saw in the bank conference room. Carr points to vacant lots and apartment buildings where black-owned businesses and clubs once stood. We make a stop in the parking lot of Columbia Savings and Loan, the first African American–owned savings and loan association in the city, founded by Ardie and Wilber Halyard to help black residents secure loans at the height of redlining.

For many aspiring black homeowners in mid-century Milwaukee, Columbia Savings and Loan was the only place to turn to, as other banks adhered to “residential security maps” designed by the FHA-back Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) in the 1930s.

HOLC created these maps with the help of local mortgage lenders and real estate appraisers. The maps used color coding to rank neighborhoods based on risk and credit worthiness: green (“best”), blue (“still desirable”), yellow (“definitely declining”) and red (“hazardous”).

Residential security map of Milwaukee from 1938; compiled from official records and drawn by Maurice Kranyecz; published and sold by David White Co., Inc.; prepared by Division of Research and Statistics with the co-operation of the Appraisal Department Home Owners’ Loan Corporation.

In Milwaukee, as in other cities across the nation, black and immigrant neighborhoods consistently received the worst ratings. Paired with racially restrictive covenants that barred black residents from buying property in the suburbs, redlining intensified segregation throughout the U.S. and made it nearly impossible for African Americans to obtain mortgages, thereby stunting their ability to attain and grow wealth.

In addition to color coding, each neighborhood map came with a qualitative summary.

District 5 is one of the most egregious examples among Milwaukee’s 1937 security maps. The neighborhood was described as a “negro and slum area” inhabited by “laborers and ne’er-do-wells.”

Under the D5 map’s clarifying remarks, the assessor added: “Besides the colored people, a large number of lower type Jews are moving into the section.”

Our next stop is a few blocks west where we meet Ariam Kesete, a young black developer who is converting a dilapidated building in the Washington Park neighborhood into a start-up incubator. We file into the vacant building, which is currently stripped down to its studs and undergoing repairs for water damage. The space will house accounting, marketing and health care services for small business owners, along with a coffee shop.

For Carr, getting off the bus is an important part of the experience. “The association people have with bus tours is that it’s passive, that you’re just looking through the window at something,” he says. “I wanted to get people out of that spectator role of just seeing things through the windshield.”

In 1937, D11 received the lowest (“hazardous”) rating from HOLC, along with comments about the area’s Polish population and one final remark that’s personal for Altoro: “Mexicans are encroaching in the northeast.”

“The wording just blew me away,” says Altoro. “That right there is a direct reference to my family.”

Kesete tells the group she wants the incubator to nurture entrepreneurs from the neighborhood. “We’re creating a hub for people to have a startup business so they can grow and then relocate elsewhere as the neighborhood gets up to speed,” she says. By supporting the residents of Washington Park, Kesete hopes to mitigate any risk of gentrification, which could displace the immigrant families who live in the neighborhood today.

Altoro says the key to avoiding gentrification is supporting developments that are “favorable to the culture and the race of the people” already living in the neighborhood. He cites Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood, a Mexican enclave, as an example of a thriving local economy. He starts naming local businesses, art museums and dulcerías (Mexican sweets shops) as evidence.

“Who knows what a dulcería is?” Altoro asks the group. A few of us raise our hands. “If you don’t know, it doesn’t matter. It’s not for you, it’s for them!”

The tour wraps up back south in Walker’s Point, a historically Hispanic neighborhood that is often described today as “up-and-coming.” It’s home to some of the city’s most expensive restaurants, cocktail bars and loft apartments.

Altoro was born and raised on the south side. His grandfather was one of the first Mexicans to arrive in Milwaukee in 1915 to work at the Pfister & Vogel leather tannery. His grandfather also had 17 children in Milwaukee — Altoro credits him with the early growth of the Mexican community here. “If I were to run for office I would have an amazing built-in constituency,” he jokes.

The bus pulls up to the block where Altoro’s grandfather lived when he first arrived in Milwaukee. Altoro holds up a blown-up poster of the redlining map description for District 11, where our group now stands.

In 1937, D11 received the lowest (“hazardous”) rating from HOLC, along with comments about the area’s Polish population and one final remark that’s personal for Altoro: “Mexicans are encroaching in the northeast.”

“The wording just blew me away,” says Altoro. “That right there is a direct reference to my family.”

* * *

The tour doesn’t conclude with a neatly delivered summary or a call to action for the group, which is mostly white and ranges in age from Millennials to Baby Boomers.

“Adam and I are really okay with not having this specific outcome, like we want people to organize and do something,” says Altoro. “We’re really comfortable with the fact that we left it here, now let’s see what type of impact and effect it has.”

Joaquin Altoro in front of his grandfather’s house, holding a blown-up poster of the redlining map description for District 11. [credit: Lauren Sieben]

“For Adam and I, we are not the normal person that’s been telling the story,” Altoro says, explaining that he usually hears about segregation and discrimination in Milwaukee from the perspective of a white reporter (this point is not lost on me, a white reporter). “I’m proud that this story is different than the one I’m used to being told.”

Altoro says he’s also proud to support minority business owners through his work: “There aren’t that many bankers who look like me working in commercial business banking in Milwaukee.”

Jackson says that on his tours, placing segregation in historical context is just as important as bringing people outside of their usual “bubbles.”

“It gives us the ability to have more normal interactions, where you just deal with people based on your shared humanity and you don’t look at people from this perspective of a stereotype,” says Jackson.

For Carr, he hopes the people who attend his tours leave with a heightened understanding for how the city’s past directly shaped its present. He hopes people pause to consider the complexity of Milwaukee’s history the next time they read a headline.

“Milwaukee is a place where there’s a lot of understanding at a distance,” says Carr. “That goes for people no matter where you are, no matter what side of the line you reside on.”

Banner photo from Detours by Carr [https://vimeo.com/137963764]

To support more journalism made by and for the Rust Belt, become a member of Belt Magazine starting at just $5 a month.