Tidyman may have taken a dim view of his hometown (an anonymous former co-worker said, “He talked about Cleveland like it was a birth defect”), but even he could appreciate its dramatic possibilities.

By Vince Guerrieri

It’s hard to view “Shaft” as anything but a New York story.

From the seedy Times Square where title character John Shaft’s private investigator’s office is located, to his Greenwich village haunts, to the uptown domain of Black radicals and a numbers kingpin based on a real-life Harlem gangster, the movie just screams Manhattan – aided by the brilliant direction of Gordon Parks, who used his skillful photographer’s eye to film on location in New York.

But the main character – the cat that won’t cop out when there’s danger all about – and his creator have their origins in Cleveland.

Ernest Tidyman “drew on knowledge obtained as a police reporter in Cleveland in creating his detective story and hard-as-nails leading character,” said a 1970 profile – right as the novel “Shaft” was coming out – in the Plain Dealer, which seemed at times to be the Tidyman family business.

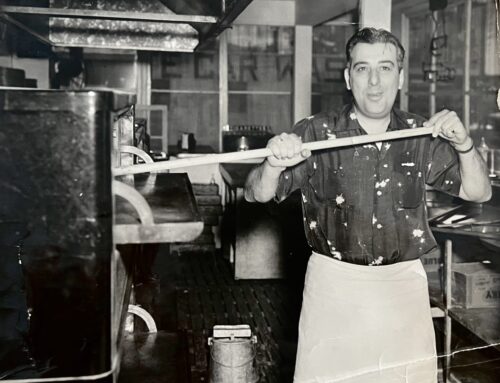

Ernest Tidyman was born Jan. 1, 1928 in Cleveland. His father Ben was hired at the Cleveland Press three years earlier, but soon would become renowned as one of the city’s best police reporters. (When the elder Tidyman died in 1955, his son Bob, who also went into newspapers, would succeed him as the Plain Dealer’s police reporter.) Ernest would accompany his father on his rounds, and Bob told a story of when the boys were out with their father, and they saw a prisoner attempting an escape from the Cuyahoga County Jail. “Let him get away boys, and then call the desk,” Ben said. “It’s a better story if he escapes.”

Ernest wasn’t a particularly diligent student, nor was he interested in school, so at age 14, he left, “by mutual consent,” he said in an interview after fame and fortune had come to him. He answered an ad in the back of Editor and Publisher for a reporter’s job in Connecticut, and his journalism career was on its way.

He went on to work at the Cleveland News, an afternoon newspaper that was owned by Forest City Publishing, at the time the parent company of the Plain Dealer. (The News was sold in 1960 to Scripps-Howard, the owner of Cleveland’s other afternoon newspaper, the Press, and was shut down.)

While at the News, he covered one of the biggest disasters in Cleveland history. On Oct. 20, 1944, one of the above-ground storage tanks for liquefied natural gas began to leak at the East Ohio Gas complex on Cleveland’s East Side. The gas was ignited, leading to a massive explosion and a fire that burned for almost an entire day. All told, 130 people were killed. Of those, 61 were burnt beyond recognition. “I was at the morgue watching them putty-knife people out of metal lockers where they’d attempted to duck to escape the flames,” Tidyman recalled.

His journalism career was an itinerant one, with stops in Houston, Detroit and finally New York City. (Part of it might be that he had traits that made it easy for him to wear out his welcome. By his own admission, he was an alcoholic starting in his teens, and Joe Eszterhas – another Cleveland journalist who found success in Hollywood – said Tidyman was fired at least once for stealing a watch from a jewelry store while he was there covering a robbery.)

But he always seemed to gravitate back toward Cleveland. It was, after all, an interesting city, especially if you were a crime reporter at heart, like he was. “I covered everything from crime to concerts, whatever circumstances dictated,” he said in an interview with Publisher’s Weekly. “But I found myself more interested in people in the streets than people in penthouses. Crimes occur in both places, but there’s more drama on the street.”

Eventually he left newspapers, but the crime reporter’s sensibilities never left him. He latched on as a writer with Magazine Management, a company started by Martin Goodman (the founder of Marvel Comics) that published a variety of magazines for men. The company employed a stable of writers, and Tidyman found a home there publishing features. (Another writer worked there, with a similarly interesting career arc that would end up in Hollywood: Mario Puzo. A civil servant, he’d written two critically well-received but poorly selling works before writing an organized crime potboiler strictly from research. “The Godfather” would become a runaway success and his meal ticket as a writer.)

From there – as much out of financial necessity as anything else – Tidyman branched into writing novels. He asked what kind of books a nearby publisher was looking for. He was told the hot topic was hippies, so his first novel, “Flower Power,” told the story of a teenage girl who ran away from her home in Cleveland, headed for Haight-Ashbury.

Next, he realized that there were few black heroes in the world of publishing, so he turned toward a detective story. (These were the days when any representation was good representation, so the idea of a white man creating a Black character wasn’t viewed as dimly as it might be today. In fact, Tidyman won an NAACP Image Award for “Shaft.”)

John Shaft was the logical progression of the hard-boiled detectives created a generation earlier by Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, and the book and initial movie bear out Chandler’s dictum of his detective stories:

“Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor—by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world.”

Comparisons were also made with Mike Hammer, the post-war detective created by Mickey Spillane (who also wrote for Magazine Management).

The story is about a private detective hired by a Harlem gangster (he’s Knocks Persons in the book; by the time movie came out, he was Bumpy Jonas, no doubt a reference to Bumpy Johnson) to find his missing daughter. In the book, she was herself a drug addict. She was made an innocent – a college student – in the movie. The New York Times called the book “violence for violence’s sake,” but it was quickly optioned by MGM for a movie.

Tidyman was hired to write the screenplay, and director William Friedkin had read early galleys of the “Shaft” novel, and was impressed enough by Tidyman’s ear for dialogue to hire him to write the screenplay for his forthcoming movie, “The French Connection.” Both movies came out in 1971.

“Shaft” turned into a smash. Isaac Hayes won an Oscar for his iconic score. Tidyman took home hardware that night as well, receiving the Academy Award for his “French Connection” screenplay. His credit didn’t come without a fight. Friedkin alleged that Tidyman’s contributions to the screenplay were nominal, forcing Tidyman to take his case to the Screen Writers Guild. “Friedkin couldn’t write ‘help’ on a piece of paper and throw it in the sea of problems a writer solves with his craft,” Tidyman said. “I’d be delighted to show him which end of the typewriter the paper goes into.”

Suddenly, Tidyman was a hot commodity. He wrote six more “Shaft” novels, and the screenplay for the movie sequel, “Shaft’s Big Score.” He eschewed Hollywood and New York, living in Connecticut and England. Later works included the script for “High Plains Drifter” and a TV movie on the Jonestown tragedy. (In an interview in 1981, three years before his death at 56, he talked about a project he considered his best work to date: A screenplay based on Jimmy Breslin’s book, “World With End, Amen.” It never came to fruition.)

He also wrote a novel, “Line of Duty,” that took place in Cleveland (the Plain Dealer called it engrossing; the Press took a dimmer view, saying it relied too much on cliches), and included a memorable, if slightly insulting, dedication. The book was dedicated to his father, and included this nugget of wisdom he’d passed to his son one night at the Cleveland police station. “Ernest, there is only reason this burg Cleveland exists,” He recalled his father telling him. “It’s a place to stop between New York and Chicago and piss in the river.”

Tidyman may have taken a dim view of his hometown (an anonymous former co-worker said, “He talked about Cleveland like it was a birth defect”), but even he could appreciate its dramatic possibilities.

“Someday, I hope to do a movie in Cleveland,” he said while working on the “Shaft” screenplay. “It’s a really tough, sharp-angled city, an industrial, strong, vigorous place.”

Vince Guerrieri was born in Youngstown three weeks before Black Monday, and left there without ever really escaping it. He’s an award-winning journalist and author now living in the Cleveland area.