By Daniel Goldmark

Not long after I moved to Cleveland in 2005, I started researching the city’s music history. I discovered dozens of songwriters who created music about life in Cleveland during the early 1900s. Most of these songs were printed as sheet music by now-defunct Cleveland music publishers.

I was delighted. My research and my writing center on the history of popular music, in particular on how people experience songs–whether as a piece of highly decorated paper you could buy in a music shop, as background music heard in cartoons or films, or featured as a performance in a Hollywood musical (to name just a few options).

So I kept–and keep–looking for more evidence of Cleveland’s popular music history. I find sheet music all around town: at garage sales, antique shops, library book sales, and when friends of friends give me a call. Hardly a week goes by before I discover something previously unknown. That’s the fun of my work and my hobby—I’ll probably never see the end of it.

Here are a select few that stand out from what I’ve found in seven years of digging.

Yes, We Got It, No Hot Dogs (1924)

Yes, We Got It, No Hot Dogs (1924)

This song with a very unusual title is a great example of a regional hit, one that never moved beyond the boundaries of the greater Cleveland area. In 1923 the entire country was grinning—or groaning—to the strains of the latest novelty song, “Yes! We Have No Bananas!” The banana song came from a 1922 revue Make it Snappy starring the Broadway performer (and later radio, film, and television star) Eddie Cantor. The song and the expression was a pop culture phenomenon, showing up in every imaginable context. Like other pop phenomena, however, the craze wore thin very quickly; a song bemoaning the phrase and its music was published the very same year as the original, titled “I’ve Got the Yes! We Have No Bananas Blues.” This hot dog song, written Herman Hummel, a prolific Cleveland-based songwriter and arranger, was a featured dance tune at Luna Park in the summer of 1925.

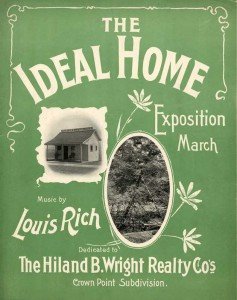

Ideal Home

Ideal Home

What better way to sell a home in turn-of-the-century Cleveland than by providing a song that lets the buyer imagine himself singing at the piano, gathered in the secure bosom of a loving family?

The back cover of “The Ideal Home” includes a lengthy sales pitch for the new Crown Point Subdivision, situated “on Noble Road, between Euclid Avenue and Mayfield Road, destined to be another East 105th Street.” The price? “$800 to $1000.”

The song’s composer, Louis Rich, was a Cleveland-born songwriter and bandleader who graduated from East High and wrote several songs-on-demand for Cleveland functions or businesses, including theme songs for the Cleveland Automobile Show in 1915 and another for the Euclid Ave. Opera House (in 1908).

I found this sheet in an antique store on Mayfield Road not far from the area described in the sheet’s ad copy; my guess is that someone nearby sold or donated the contents of their piano bench (or, more likely, a box in their attic) to the shop, which would explain why it was so close to its point of origin. The idealist in me imagines a copy of this sheet left as a welcome gift on the fireplace mantle of each new home in the Crown Point Subdivision.

On the Sands

On the Sands

Clevelanders had a wide variety of public beaches, amusement parks, and other forms of diversion to choose from in the early 1900s, and most offered live music by local bands or orchestras for the park-goer. While famous places like Euclid Beach Park and Luna Park attracted thousands, public beaches were also very popular.

Gordon Park opened in 1893; people could fish, swim, boat and use the bathhouse, which is prominently pictured on the sheet music cover. The song’s composer, Calvin D. Paxson, best known in Cleveland as a car dealer and owner of Paxson Motors, was an aspiring songwriter who penned quite a few songs, including several extolling the automobile he sold, the Jackson, whose catchphrase was “No Hill Too Steep, No Sand Too Deep.”

Adelbert Two-Step

Adelbert Two-Step

Adelbert Hall was constructed in 1881 as the first building of the newly relocated (from Hudson to Cleveland) Western Reserve University. The song’s composer was James D. “Jimmy” Johnston (c.1871-1933). While it’s unclear if Johnson went to Western Reserve, he certainly had a propensity for college songs; an article in the Plain Dealer from the same year as “Adelbert Two-Step” indicates that he also wrote a “University Two-Step” and “Case Grand March” (neither of which I’ve ever seen); he also wrote “Yale Varsity” for Cleveland music publisher (and instrument maker) H.N. White in 1901. Johnston was the first principle viola for the Cleveland Orchestra (in 1918) and a member of the Cecilian String Quartet and Philharmonic String Quartet. He also had his own group, the Johnston Society Orchestra, which played in ballrooms and homes throughout Cleveland until his untimely death in his early 60s from a heart attack, suffered while watching a boxing match at the Cleveland Athletic Club.

What dates this song most clearly to 1896 is the dedication to “the Adelbert Mandolin Club.” The photograph of the presumed Club showcases a variety of stringed instruments, including a cello, violin, guitars, and mandolins. Instrument clubs were extremely popular for all ages at the turn of the 20th century, and playing the mandolin was all the rage.

My Name Will Always be Chickie

My Name Will Always be Chickie

Famous stories ranging from The Count of Monte Christo to The Maltese Falcon first appeared in serialized installments in magazines and newspapers before being published as standalone books. I’ve found a craze of sorts for songs inspired by 1920s serials in The Cleveland News. Many were by Isobel K. Robertson, a Lakewood resident who authored six songs between 1925 and 1929. While some of these songs didn’t get much more than local exposure (read: they never left Cleveland), a few were regional or even national hits, including Robertson’s “Nora Lee,” and “My Name Will Always Be Chickie,” written and popularized by Phil Spitalny, a bandleader who first gained fame in Cleveland with his “all-girl” orchestra and went on to host a radio show heard around the country with the same women’s orchestra, called the “Hour of Charm.”

Cleveland Industrial Exposition March

Cleveland Industrial Exposition March

At the turn of the 20th century, expositions and world fairs were a very popular way for cities (or countries) to showcase technological advances, trumpet their own ideas of social progress, and create hundreds of jobs and generate revenue. Ohio had many such expos, and songs for them go back at least to the “Cleveland State Fair Waltzes” from the Ohio State Fair in 1852.

The Cleveland Industrial Exposition of 1909 generated at least three songs that I’m aware of, one featuring an original design for the fair by famed artist Ora Coltman, one featuring a statue titled “Spirit of Progress” which was designed by Exposition architect J. Milton Dyer and executed by sculptor Herman Matzen, and the Exposition’s “official” publicity image, which highlighted the main exposition building, located where Cleveland City Hall now stands.

Fluffy Ruffle Girls Rag

Fluffy Ruffle Girls Rag

Here’s a perfect example of a Cleveland-published sheet taking on a current pop culture trend. “Fluffy Ruffles” referred to women trying to succeed in the male-dominated workforce. It began as a comic strip in the New York Herald in 1906; within a year there were more than a dozen songs published that either had “Fluffy Ruffles” as the title or made reference to “fluffy ruffle” girls. Producer Charles Frohman mounted an entire musical comedy on the theme in 1908, with music by none other than Jerome Kern. Besides the connection to a pop culture trend, the cover’s artwork also gives us a vivid snapshot of women’s fashion in early 1900s; note that each woman’s ensemble varies slightly from the others’, not simply in color, but in the hat design, number, size and color of buttons, neckwear, and hairstyle.

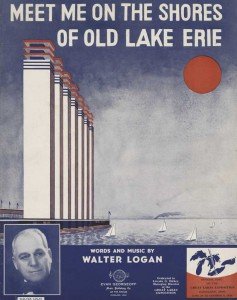

Meet Me on the Shores of Old Lake Erie

Meet Me on the Shores of Old Lake Erie

The Great Lakes Exposition, which ran in the summers of 1936 and 1937, generated more publicity and buzz nationwide than any other fair or event held in Cleveland, including the Industrial Exposition of 1909. Following the mold of world fairs of the past, the Exposition had streets and midways featuring food and commerce from all over the United States and the world, as well as rides, games, and various halls dedicated to history, art, science, and nature.

Live music was a major part of the entertainment, and nothing was more entertaining than producer Billy Rose’s song-and-dance-and-swim extravaganza on water, the Billy Rose Aquacade, which only appeared in the 1937 season. The show featured Olympic gold medalists Eleanor Holm and Johnny Weissmuller; both were Hollywood stars, and in 1937 Weissmuller was starring in the very successful Tarzan movies.

Most of the music associated with the Exposition came from the Aquacade show and was published by a mainstream New York music publisher. I was thus pleasantly surprised to find a copy of this “Official Song of the Great Lakes Exposition” in a sheet music collection I acquired from a lifelong Clevelander. The song’s composer was Walter Logan, who was not only a well-known bandleader on the radio and in concert venues, but also was a one-time head of the Music School Settlement and was among the violinists in the original formation of the Cleveland Orchestra.

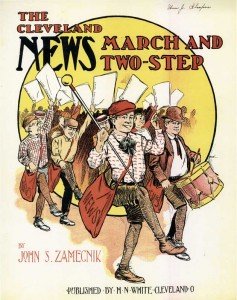

Cleveland News March and Two-Step

Cleveland News March and Two-Step

This piece had and always will have a specific significance for me, in that it is not only an early 20th century song from and about Cleveland—always a plus—but it was (as far as I knew when I found it) the earliest published song by John Stepan Zamecnik. Before setting my sights on Cleveland music, I spent most of my time writing about and watching Hollywood cartoons. Early cartoons—from the late 1920s and through the 1930s—relied a great deal on pop songs and silent movie mood music to fill their soundtracks. Zamecnik was one of the most prolific (and therefore most heard, even though most people have never heard of him) composers of mood music for films, also called photoplay music.

Zamecnik (1872-1953) was a Cleveland native who studied in Prague in his early 20s with Antonin Dvorak before returning to Cleveland, where he was very active as a composer and performer at the turn of the 20th century. He played violin in local orchestras as well as making periodic trips to play in the Pittsburgh Symphony under conductor Victor Herbert; he was the first music director of the Hippodrome Theatre, which opened in late 1907; he was also the staff composer at Sam Fox Publishing. This piece, published by local instrument maker and sometime music publisher H.N. White, commemorates the newly-created Cleveland News, which began (out of the merging of three other papers) in the summer of 1905. The song also is one of the dozens of pieces celebrating newspapers in the United States, the most famous example of which was John Philip Sousa’s “Washington Post March.”

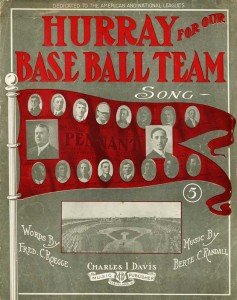

Hurray for Our Baseball Team (1909)

Hurray for Our Baseball Team (1909)

I have several songs about the Indians and even the Browns, but I chose this early song—published in Cleveland—because the cover pictures several major figures from turn of the century baseball. What makes this cover unique is that the men pictured are managers, including many player-managers.

The manager of the Naps, the Cleveland team at the time, was Napoleon Lajoie; he’s pictured at top left (his popularity as a player led the team’s name to be changed from Bronchos to Naps). Next to LaJoie is Jimmy McAleer, who in 1909 was manager of the St. Louis Browns, but began his career as a player with the Cleveland Spiders and Cleveland Blues. (The stadium pictured is not in Cleveland, by the way; the caption indicates the field is National League Park in Chicago.) While the song’s lyrics name almost every major team in the country, the writers figured some smaller teams might want to use the song too: there is a note at the bottom reminding the singer to fill in the “name of your city when singing.”

Daniel Goldmark is Associate Professor of Music at Case Western Reserve University. Email him at [email protected] if you have some sheet music treasures in your attic…

“Sing It, Cleveland” by Daniel Goldmark appears in Dispatches from the Rust Belt: The Best of Belt Year One, our first-year print anthology. Order the book here: http://bit.ly/BestOfBelt

Very cool. I’d sure love to hear some of these! What a great history we have in CLE.

Ditto, Ditzenberger. Very interesting article. Thanks.

Fascinating! Write more!

Awesome article!

WOW!! How cool 🙂

Prof: Goldmark:

Saw your presentation at Happy Dog U. last night and it was great. Nothing like sing-a-longs with a ukulele and millennials waving their beer mugs and singing a song written in the early 1900s about having to move back into your father’s house in Cleveland. My first thought was why don’t the pro-Cleveland non-profit promotional agencies (and there are plenty of those), use these classic old Cleveland songs in some way to promote Cleveland? Just a thought.