I’d recently finished my junior year of high school and was kicking around a few ideas on how to get out of Locksburg, a Central Pennsylvania backwater I’d wanted to flee ever since I was old enough to misspell its name.

By Ken Jaworowski

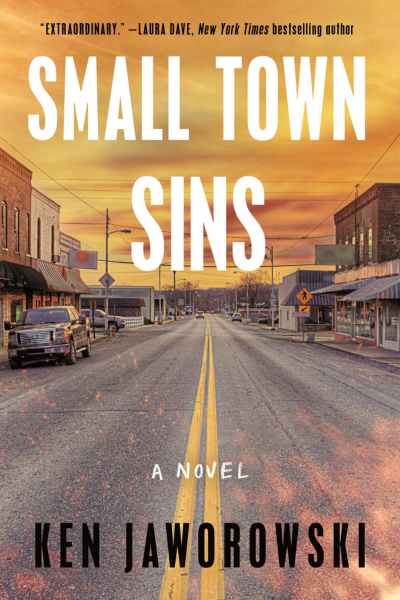

Ken Jaworowski’s debut novel, Small Town Sins, was published by Henry Holt & Co. on August 1. The thriller is set in the fictional Locksburg, Pennsylvania, a former coal and steel town whose best days are long past. There, three restless souls have their lives upended: Nathan, a volunteer fireman who uncovers a secret stash of money in a burning building and takes it; Callie, a nurse whose tender patient may not have long to live, despite the girl’s fundamentalist parents’ ardent beliefs; and Andy, a recovering heroin addict who undertakes a nightmare mission to hunt down and stop a serial predator.

Ken is an editor for The New York Times who grew up in Philadelphia. He went to college in tiny, rural Shippensburg, Pa., one of the places that helped inspire the setting of “Small Town Sins.”

In this, the opening pages of the novel, a character named Nathan recalls growing up in Locksburg.

I can trace so much of my life back to a summer night when I was seventeen. Everything starts from then and links the years that follow, like one of those connect-the-dots pages you played with as a kid: Begin right here, draw a line to there, then another, then again. Sooner or later, an image emerges.

I’d recently finished my junior year of high school and was kicking around a few ideas on how to get out of Locksburg, a Central Pennsylvania backwater I’d wanted to flee ever since I was old enough to misspell its name. College was a possibility. The marines, a cheaper one. Either would work, as long as it got me away.

I had a nodding acquaintance with my classmates but no real friends among them. That’s not because of bad behavior on my part. The opposite was true: I was the only child of a sweet-spoken, disabled mother and a deacon father who together looked after a struggling church that was too poor to support a full-time priest. When I wasn’t doing schoolwork or house chores, I was at Saint Stanislaus, chipping melted wax from the candleholders or cementing the cracks that the bitter winters brought to the stone walls outside.

One Saturday night I was walking home from the church, head down, hands in pockets, when I turned a corner. LeeLee Roland was bounding down the steps of her house, ten yards away. She was a soon-to-be sophomore who stood out from the other girls at school. Even at fifteen, she was brazenly flirty to most every guy but me. I’d watch her with a side-eye, fascinated but wary, as she bounced along the high school halls.

“Hey, Nate!” she called, employing a nickname I didn’t use. I raised my chin and hid my surprise. We’d never spoken before, and I was a little amazed that she knew who I was.

“You going to the party too?” she asked.

“Nah,” I said, as if I knew which party that was.

“Yes, you are. I’m kidnapping you.”

She hooked a hand around my arm, and the breath left my lungs. To feel a girl touch me, even with just a friendly move, nearly froze me. That touch, combined with the warm June breeze, was instantly intoxicating, as if I’d swallowed an entire bottle of altar wine.

“Where is it?” I said, tamping down my voice in the hope of sounding somewhat cool.

“Tracy’s house,” LeeLee said. “Willow Street.”

I nodded a few times too many while piecing it together: Tracy Carson lived there, another girl I’d never spoken to. LeeLee and I walked two blocks then turned onto Willow.

“I’m . . . I’m not really sure I’m invited,” I said, entirely sure I wasn’t.

“She don’t care. Anyway, too late,” LeeLee said, and turned to walk up the steps of a house. She let go of my arm. I felt both real relief and deep disappointment.

LeeLee courtesy-knocked then pushed the door open. Inside, about fifteen people were circled around the dining room table, playing some kind of drinking game. All were familiar faces. In a town of about five thousand, you saw everyone at one time or another.

“Look who I found,” LeeLee told the group. They seemed indifferent. For that, I was grateful. Anything short of disdain was enough to make me half happy. Like any seventeen-year-old, I was perpetually confused and occasionally anxious, all while acting as confident as I could.

Forty-five minutes later, the number of people had nearly tripled, and the radio, blaring classic rock, had gotten turned up twice as loud. I’d taken a place against a wall, nursing a can of lukewarm Keystone Light and watching the games that no one asked me to join. After finishing my beer, I acted as if the can were full, bringing it to my lips time and again. LeeLee had gone to the kitchen and brought me the beer when we’d arrived. She’d since disappeared upstairs with a pack of other girls.

I debated leaving. No one would notice.

I eyed the door.

Any time up until then had been pivotal, of course. What if I had stayed at church a few extra minutes and never saw LeeLee? Or what if I had taken another route home? But when I look back, that moment seems the most decisive, the last real instant when something could have changed. Had I walked out that door then, how many lives would have been different?

Ken is an editor at The New York Times. He graduated from Shippensburg University and the University of Pennsylvania. He grew up in Philadelphia, where he was an amateur boxer, and has had plays produced in New York and Europe. He lives in New Jersey with his family. Small Town Sins is his first novel.