Since the early twentieth century, the area has been a safe haven for Latinx—including my family.

By Christiana Castillo

“They tried to bury us, but they forgot we are seeds” – Mexican Proverb

On the corner of Fisher Freeway and Vernor in Southwest Detroit is a large empty lot of land. It’s on a dead end, close to a freeway entrance. To most people, this strip of land and the dead-end street it is attached to are probably an inconvenience, a source of confusion. But it is a special place for me. This patchy, littered plot of empty land was the home of my great-grandparents, Telesforo and Maria Dolores Hernandez, when they moved to the United States from Mexico in the 1920s.

Whenever I am in Southwest Detroit, my mind fills with the history my family has here. My great-grandparents were two of thousands of Mexicans that fled Mexico due to the Cristiada, a persecution of Christians, more specifically Catholics, during the early 1920s.¹ They were married in secrecy in Jalisco, Mexico by a Catholic priest. They then sought a place of their own, free of persecution. For them, this place was Southwest Detroit.

To many immigrants, Detroit was a place filled with opportunity. Mexicans migrated to Detroit from the states of Jalisco, Chihuahua, Guanajuato, Zacatecas, Durango, and Michoacán, and Mexican Americans migrated from southern states. There were many jobs available in the city. Word carried that Detroit was not as racist toward Mexicans as other places in the United States. Mexican immigrants found jobs working for railroad and automobile companies, as well as the sugar beet industry, steel mills, and other factory jobs.

My great-grandfather got a job working on the railroads. The work was hard, and the pay was minimal, but he was able to make a living for himself and his wife Dolores. During the 1920s the railroads were one of the largest ways Mexican immigrants got to “El Norte.” So my great-grandfather helped pave the way for Mexican immigrants, literally and figuratively, to come Detroit. They shared their experiences about the different places they fled, and word traveled that they were treated with less discrimination in the Midwest than any other place.

Shortly after they fled from Mexico, they were able to acquire two houses on what used to be Beecher Street, but is now the Fisher Freeway Service drive. Here, the Hernandezes built their lives. Their friends and neighbors owned the other three homes on the street. Their homes were small, but filled with family, friends, and other immigrants.

Telesforo dug a basement underneath their homes to allow space for immigrants who were still saving up money for their own places, or for doctors or other expenses after fleeing from Mexico. Their homes and houses were sanctuaries. Here, in their homes in Detroit, the Hernandezes did not have to worry about being killed for their religious practices. They made money, and were able to help their friends and family members who were still in Mexico.

According to the U.S. census of 1900 there were fifty-six Mexicans living in Michigan. By 1910 there were eighty-two. The U.S. census of 1920 found approximately 1,268 Mexicans in Michigan, but historians estimate there were more than four thousand in Detroit alone, many of them undocumented and uncounted. By 2015, 72.6 percent of the population in the Southwest Detroit area consisted of Latinx and Hispanic peoples. The ancestors of many of the current citizens in Southwest Detroit paved the way for the current generation.

These days, the southwest Detroit area remains a beacon of tradition and culture. In the early part of the century, the new Mexican and Mexican American community—my family included—was able to create a safe place, filled with their culture and traditions, free of fear, which continues today. This space extends as the population occupies the geographical area. It roughly extends over roughly 2.7 square miles. If you try to find a map of southwest Detroit, you will get many different visual results. But I would argue that it’s a place that is defined by its essence, and not by lines on a piece of paper.

In Southwest Detroit, you are slammed with Latinx culture. When I drive through Southwest nowadays, if I try to keep count of the Virgin de Guadalupe statues in gardens, I lose count. There are taco carts, church bells ringing, and a population that is made predominantly of Latinx people.

I grew up hearing the sounds of church bells at Sainte Anne Parish de Detroit, on Ste. Anne Street between Howard and Lafayette. Out of all the churches I have ever gone to, it is the church that feels most sacred to me. My ancestors and my family all grew up going to Saint Anne’s. It was built by the French, but now primarily serves Latinx Catholics. They offer bilingual mass in Spanish and English. Almost every Christmas Eve, my family would attend mass for the Christmas novena, then pick up Mexican sweets at La Gloria bakery. We still do. My great uncle served as radio host for the Ste. Anne’s radio show. My aunts and mother grew up giving tours of the building.

Ste. Anne’s was not and is not the only church that serves as a site for religious traditions of Mexico. Most Holy Trinity Church, on Porter Street, has been a staple since Mexicans first started migrating to Detroit. In the early 1920s, the Mexican and Puerto Rican community in Southwest instituted Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church. Religion, especially Roman Catholicism, is vital to the lives of many Mexicans and Mexican Americans. In the 1930s and 1940s, many religious groups were created in the community, such as: Los Caballeros de Cristo (Knights of Christ), Las Guadalupanas, Las Hijas de Mexico (The Daughters of Mexico), and Los Cursillistas, a Christian Movement organization.

This energy extends throughout Southwest Detroit. Latinx pride is woven throughout the territory, including Mexican music and folkloric dance opportunities. My mother grew up on Beecher Street. Here in southwest Detroit she felt she grew up living the Mexican American experience. She was able practice her religion, celebrate her heritage, eat traditional Mexican food, but also American food. Mariachi bands can be found practicing in the evenings in parking lots. Young children practice folkloric dances to perform for religious and cultural holidays.

As the Latinx/Hispanic population has grown in Southwest, it’s shaped the business community. In Southwest there are more than a thousand small businesses owned by Latinxs. Mexicantown thrives with bakeries, bars, and restaurants. However the small businesses extend outside of the commercialized Mexicantown area. The supermercados E&L and the Honey Bee La Colmena allow for the foods and traditions of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans to be easily accessible to the community. The Honey Bee La Colmena has significantly expanded since its founding in 1956, from four thousand square feet to fifteen thousand.

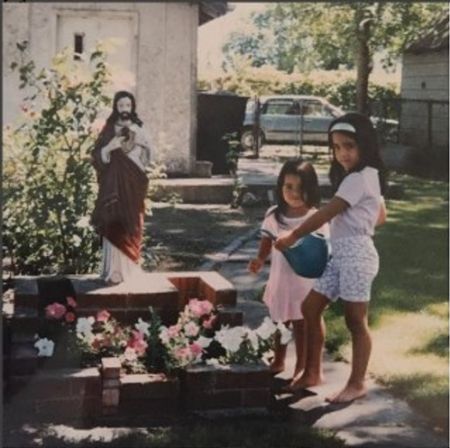

Beecher street was a place for Mexican immigrants, a place that allowed for the celebration of religion and tradition. Here Mexican Catholics did not have to hide their beliefs, but showed them with pride. My great-grandparents had their own family—two daughters, Elva and Thelma, and a son, Hector. They had a garden filled with shrines to Jesus Christ and the Virgen de Guadalupe in their yard. My sister and I used to climb over their statues and water flowers beneath their ceramic feet when we were young. We grew up learning to take care of the Earth, and knowing if we prayed to God, Jesus, the Virgen, or any of the various Catholic saints, we would live blessed lives.

My grandmother and great-grandparents loved their religion, and celebrated it everywhere they could. Their backyards with their shrines with flowers, rosaries hanging off rear view mirrors, prayer cards and saints pinned on the interior roofs of their cars, busts of Popes, prayer candles, and posters of the Virgin de Guadalupe were woven throughout their homes. When I drive, I have a sparking blue rosary hanging off my rear-view mirror that was passed down to me from my grandmother. I was given her prayer cards from her car and pin them proudly in mine now.

My grandmother, Elva, moved into the home directly next to my great-grandparents’ home and raised her six daughters by herself. Her parents taught her a strong work ethic, and she was able to send all of her daughters to Catholic private schools. She was proud of the way she was able to honor her heritage and religion in this way. My mother enjoyed going to Holy Redeemer school, but my aunts were not as enthusiastic, because of how strict the nuns were. To follow in her mother’s footsteps, my mother sent both my sister and me to Catholic schools throughout our lives; all of my aunts have done the same for their children.

My grandmother was eventually able to acquire an empty lot of land next to her home. Here she planted vegetables, herbs, and flowers. She planted a garden with peppers, cilantro, tomatoes, and other staples. You could always hear the humming of bees and the sounds of cars zooming on the freeway. There were vibrant flowers all around. When I was young, she had me harvest and take care of her garden with her. She was the person who taught me to always water plants close to their roots, so they can grow and spread.

My grandmother’s home and backyard are a sacred space to me. It was where I learned how to carry on Mexican traditions. If a bee ever stung me, I filled the sting with dirt, which is what my great-grandparents claimed they did back in Mexico. We would make homemade salsa and homemade tortillas in her kitchen. Right behind her garden was a meat packing plant. Strange scents of meat and fresh vegetables mixed in the air when I would visit her. An ice cream man would come down her street offering Mexican popsicles with bells jingling in his hands. If we did not want ice cream, my grandmother was always up to walk with us to La Gloria bakery for Mexican treats.

Today, Beecher Street is gone. The land my family lived on is desolate, covered with patchy grass, litter, and a billboard. You can turn onto the empty street, but it leads to a dead end. The meat packing plant is now a pickle canning plant. My grandmother, and the other owners of the homes on the Beecher street block, sold their property to the The River Tunnel Partnership, a Canadian company that operates of of Mississauga, Ontario. The company intended to expand the Michigan Central Railway Tunnel that had not been used for many years. This company was then bought out by The Continental Rail Gateway, and nothing has since been done with the land. It sits vacant.

But Southwest Detroit is still a place of refuge. Resiliency is carried throughout the community. Freedom House, a safe space for asylum seekers behind Ste. Anne’s Parish, carries on the tradition of which my family is a part. (I grew up going to church, seeing Freedom House, and knowing that this place was safe.) There are now sizeable Yemeni and Syrian populations in Southwest; people of different backgrounds are still looking to the area as a place of safety.

There are community and personal gardens throughout the neighborhood—like Native American Health Services, and its gardening program, Sacred Roots. Sacred Roots focuses on planting native plants, herbs, and vegetables to have accessible to their community. They try to reach demographics beyond the Native community. Since the Yemeni population has gone up in Southwest Detroit, Sacred Roots has been trying to engage new members. Jardin de los Santos is another community garden, and hub for people in the Southwest community to get their own gardens started. At the entrance to Jardin de los Santos is a large painting of the Virgen de Guadalupe.

Pride for “mother” countries is alive in Southwest, through shrines, places of worship, gardens, music, gatherings, and people. The area is a home, a haven, and an ever-growing community that exists because of immigrants. People like my family, who have found refuge there. ■

Christiana Castillo is a Chicana writer, educator, activist, and urban gardener based out of the greater Detroit area.

Cover image courtesy Christiana Castillo.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.