By the time she was four, my grandmother had survived her first global pandemic. A lifetime later, she is weathering another from the safety of her Cleveland home.

By Jennifer Winegardner

When the Spanish flu came to Cleveland, in the fall of 1918, Stella was three years old. She’d already been quarantined at City Hospital for tuberculosis and survived pneumonia. She would survive more: The Torso Murders, Great Depression, and the Second World War. She would live her entire life on the west side of the river that burned, in the suburbs of a city gone bankrupt; when car bombs were common, when the National Guard shot those kids. She would be a seamstress and factory girl and working mother. She would pay union dues for thirty years and retire with health insurance and a sturdy pension. And she would outlive her four sisters, her husband, and her firstborn.

Now, at 104, Stella—my grandmother—is living her denouement, unpacking her memories as they demand, completely unruffled by coronavirus. But in 1918, she was a toddler in a global pandemic, the fragile daughter of an immigrant who’d been sent to Cleveland—Tremont to be exact—in 1914 on just a prayer and a promise from St. John Cantius. Poles had been stripped of their country, denied their language, and forbidden an education. By February 1915, my great-grandmother had married, and by November, my grandmother was born. They lived in shoddy rentals built by unskilled workers who couldn’t hammer fast enough. Four more daughters were born. One would die before she could walk. The husband came and went, back and forth to Detroit. He eventually went for good. Stella, with her mother and sisters, moved from Professor to University to one rental after another, a step ahead of landlords. Always in Tremont, close to St. John Cantius, where they had Polish church and Polish school and Polish merchants.

Support independent, context-driven regional writing.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, and for most of the next fifty years, Cleveland swelled with immigrants who spilled over the city’s borders and created a horseshoe of insular neighborhoods, with Lake Erie to the north and Cleveland proper in the center. They said the world had been turned upside down and shaken, and everyone who fell landed in Cleveland. People showed up from Poland, Russia, Germany, Slovakia, Lebanon, Italy, Ireland, Israel, Mexico, and the American south, to work in the quarries and steel mills, the docks and auto plants, refineries, tool shops, and fabric and garment factories of what became the country’s sixth largest city.

Even then, anti-immigration and racial tensions were the undercurrent of everyday life. Women’s suffrage and Prohibition were on the minds of politicians. Social welfare advocates were overwhelmed with public health crises: tuberculosis, heart disease, and pneumonia caused a third of all deaths; suicide was rampant, and industrial accidents were common. Things could have been worse: by then, modernized sanitation controlled typhoid and cholera, and a new vaccine kept smallpox in check. Groups like the Anti-Tuberculosis League, the Red Cross, and Cleveland’s own health department pushed a progressive public-service agenda that mostly transcended local politics.

But in 1918, when the Spanish flu arrived, Cleveland was slow to act. Higher-ups warned City officials that the flu was coming, but it took three weeks before they respected the warning. First reports downplayed the risk, and so many people became sick it was impossible to know who had the Spanish flu and who had unrelated pneumonia. A poor immigrant’s child like my grandmother, one who’d already been so sick, would know only that she was sick again. She would never get a formal diagnosis.

It was a bad situation under the best of circumstances, but when the flu came to Cleveland its medical directors were overseas educating the Italian government about TB. A young doctor from the Warrensville Tuberculosis Sanitarium was called off the bench. He knew about respiratory disease. He knew how it spread, and he knew how to stop it. He also understood the delicate balance of public trust and buy-in, and the economic risks of mandatory shut-down orders. He leaned on churches, civic leaders, and non-profits to educate people of all social classes and ethnic backgrounds. He rallied elected officials to voluntarily participate in self-quarantine as a show of leadership. When hospital beds were dangerously full, he ordered closures of all public meeting places—churches and schools, theaters, dance halls, saloons, bowling alleys. People had a system of window tags to alert neighbors if their home was sick.

After a month, the death rate seemed to level off. When the First World War came to an end, Cleveland’s quarantine did too. But not without casualties. In less than six months, almost forty-five hundred Clevelanders died of the flu or pneumonia. This was the highest death rate in Ohio, and worse than either New York City or Chicago. But the city eventually healed, and so did my grandmother.

When I visited my grandmother last fall, she was living alone in her west side Levittown-style ranch. I helped her down the basement steps and found an empty basket in the corner. She pointed to plastic bags here and there and inspected the contents for ribbons and baubles. Her basement is a warehouse of old wardrobe and sewing patterns, bargain-bin fabrics and faux flowers. Her upper back bends forward in a posture frozen by years of hunch over a well-worn Singer. It’s hard for her to sew anymore because she can’t seem to thread a needle. But her fingers, though crooked as the river, can still pinch a wire here and nudge a flower there until the art gods tell her the arrangement is exactly right. The ribbons and baubles were for making fall-themed centerpieces—ten of them at that—for the Senior Center raffle.

But sewing clothes was her first art, a show of rebellion when her teachers at Lincoln High School put her on the cooking track. She’d survived the TB ward and a bout of pneumonia and who-knows-what else, and she was not about to be trapped at home in a hot kitchen, cooking meals for someone else. “Back then you could study sewing or cooking, and they put me in cooking,” my grandmother said, “and I hated that. They were coming out with a new fabric, a double knit or something like that. Maybe rayon. Anyway, I wanted to learn how to sew.” She couldn’t afford the stamp for mail-away sewing lessons advertised in papers. “I used to help a woman iron clothes for extra money and I asked her to teach me. She showed me how to cut fabric. I practiced making doll clothes from scraps.”

By 1923, around the time my grandmother graduated from eighth grade at St. John Cantius and started high school at Lincoln, most public schools in big cities like Cleveland had home economics programs teaching girls to sew and cook. The goal wasn’t to advance or empower young women, but to push them back into the home after war had pulled them out to work. But women were energized and empowered and rallied against Victorian-Era subservience. They would not stay beholden to broken men drowning in liquor. My grandmother was a baby, but she was on the frontline of a new feminine autonomy at home, in the workplace, and in relationships. And she had her mother, an immigrant raising five children alone, to show her how independence worked.

By the time my grandmother turned five, in 1920, white women could vote. And by the time she asked the laundress to teach her to sew, ready-to-wear clothing had become a factory-made commodity that was affordable to the poor and working-class people in neighborhoods like Tremont. Women didn’t have to stay at home and sew their families’ clothes. Enter the Roaring Twenties, when they discarded their corsets and danced—though not without pushback. In 1926, an organization of fabric wholesalers determined that declining fabric sales were caused by “a lack of knowledge of sewing and the art of dressmaking by young women, who were given over to enjoying themselves and neglecting the domestic virtues of their mothers and grandmothers.” My grandmother wanted what most women want—to choose. She wasn’t going to stay home and sew because big business wanted her there, she was going to sew because she wanted to sew. She was going to sew because she wanted pretty clothes she couldn’t afford to buy. She wanted pretty clothes to go dancing in.

Even before 1935, when national welfare came in the form of Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Cleveland took care of its people. The women’s pension fund supported women with children who were divorced, widowed, and deserted. Catholic and Jewish charities offered food and clothes. So my grandmother’s mother got help to pay rent in Tremont and feed her children. But welfare stopped when a child turned sixteen. In 1931, my grandmother aged out. She quit school to go to work. She caught a streetcar and rode across the river and beyond the smog-thick flats to a Superior Avenue sewing factory. The garment industry was a big part of Cleveland’s manufacturing backbone. Though Cleveland’s women garment workers hadn’t yet unionized, they had the support of the International Ladies Garment Union, from New York, to negotiate better pay and better hours. Because my grandmother could sew, she could work. And because she could work, she could help her mother pay rent in Tremont and feed her younger sisters. She worked in a factory making patterns for sleepwear.

The factory manager liked Stella so much he promoted her to supervisor and gave her an office. Her $33-per-month wage turned into $66 and then $99, all of which, save $1, she gave to her mother. On payday, when the whistle blew, and with a dollar to spend, my grandmother walked back across the bridge and right up to the doors of St. John Cantius Church where Father so-and-so gave her a St. Vincent DePaul card, a golden ticket to the donation rack. She ignored sizes and style and chose for fabric. She ripped out seams and recut and sewed herself dresses for dancing on the weekends at the Aragon Ballroom on West 25th Street, or for the Sunday picnics at Euclid Beach Park. She said everyone admired her clothes, even her boss, who, she believes, never really knew how poor she was.

It was a high time to be single and in Cleveland. In the summer of 1936, when my grandmother was twenty-one, the city hosted the Republican National Convention. Prohibition had ended a few years before. The Great Lakes Exposition kicked off that summer, and event created by business and civic leaders to attract visitors and provide entertainment to the Depression-struck community. Visitors to the Expo could take a spin in the Goodyear blimp, cheer on a troupe of two-hundred-and-sixty-pound ballerinas, or peek into a French Casino and see the nude can-can dancers. Memory be damned, my grandmother still pines for the days of dances and picnics and boys. Especially after watching cable news highlighting of yet another murder, terror plot, or break-in. “What’s the world coming to,” she’ll say. “It was never this bad before.”

But, of course, it was. Smilin’ Joe Falkowski ran a Tremont neighborhood gang when my grandmother was young. They robbed at will and even killed someone in a hold-up. In ’36, Cleveland and its people were terrorized by the Torso Murders, a never-solved serial killing spree. The Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run chopped up more than twelve bodies, castrating the men and leaving their legs and arms and heads drained of blood. The victims were mostly homeless, poorer than even my grandmother and her sisters. Most victims lived in or near a shantytown in a dry riverbed on the other side of the Cuyahoga. Just one body, the last, was found west, in a gully near the train tracks in Brooklyn. Eliot Ness and his Untouchables were charged with finding the killer, but never made an arrest. These are the kinds of things she forgets.

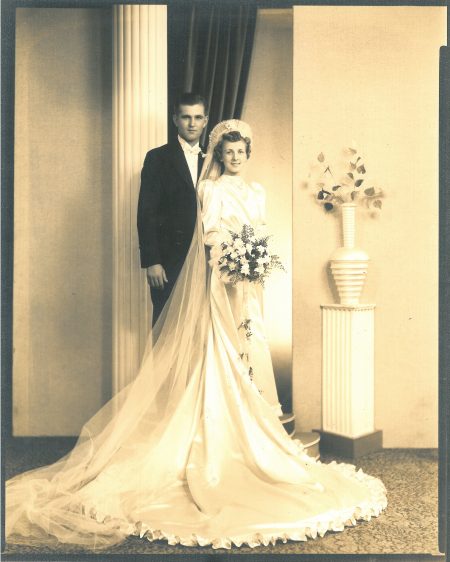

In 1937, unions were getting stronger, and people were headed back to work, Amelia Erhardt set out to fly around the world, and my grandmother met a boy. The boy. He’d come from the Firelands of Lorain, the next county west, to buy a car he’d heard was for sale in Tremont. Then he came back on his days off work and started hanging around the Aragon Ballroom on West 25th Street. He shooed away all the other boys on my grandmother’s dance card, even the Czech guy, a good dancer who lived south, off Pearl Road. The boy from Lorain took my grandmother to meet his mother. Before too long, he bought her a ring and married her. She made her own wedding gown from six yards of Champaign-colored silk that draped across her narrow shoulders into a slim skirt that ended in wide fanned swirl. She made all her bridesmaids’ dresses too.

That boy moved my grandmother out of Tremont into his own mother’s house in the next county west, where there were no dance halls or Sunday picnics. In Lorain, the neighbor women raced one another to be the first to hang their washed laundry on the clothesline. It was a life my grandmother didn’t choose or want. Her mother-in-law didn’t like her and to this day she can’t say why. Of course, she was a high school drop-out, a factory girl raised by a welfare-supported single-mother who was an illiterate immigrant. But those are things she forgets now too.

My grandmother watched her own mother manage without a man. So with a baby on her hip, she took a bus back to Tremont and her Polish community. She told her new husband he could join her and the baby if he wanted, but she’d had enough of Lorain. He told her to find them a new home, close to Tremont if she wanted. So she did. And they wound their way south, like the Cuyahoga River, landing in a new government-sponsored housing co-op project just a few miles away, in Brooklyn. And a few miles beyond that was the Municipal Airport, where her husband, my grandfather, got a job at the adjacent Bomber Plant making fighter planes for the Second World War. They had their second child, my mother, and moved to a brick house in the heart of Brooklyn. And then my grandmother went back to work.

My grandfather heard of a job at the new Chevy plant and called my grandmother to tell her they were interviewing for second shift. When the boss offered her a job starting Monday, Stella negotiated an extra week. She needed pants and blouses and a hat to meet the dress code, and she needed time to sew them. Not long after starting, she had a side hustle making hats for her coworkers. She charged $3.50 apiece. For thirty years, my grandfather worked day shift calculating numbers, and my grandmother worked afternoons inspecting small parts. It wasn’t a perfect life: my grandparents argued about money and politics and their kids. Sometimes the arguments were fights, and sometimes the fights were big. My grandmother leveled up. She had some education, a skill, and a job. She had a family. And she had a union to bargain for her fair share of the prosperity she worked hard to create.

Stella’s retirement started off as planned: she and my grandfather took group trips and ate out on Sundays. But my grandfather wasn’t healthy, and for a good ten years, my grandmother was his caregiver. The woman who started her life frail and chronically ill chose to care for her husband who’d become, at the end of his life, frail and chronically ill. He died in 1993, and since then she’s lived alone.

She has quirks. She’s always had quirks. Probably her long life is because of, not in spite of them. When people said smoking was safe, she never did it. When “health food” was weird, she bought in. She cooked and ate simple whole foods before that was a thing. She still won’t eat anything heated in a microwave because, she says, it causes cancer. The condition of her basement, brimming with fabrics and the patterns she can no longer cut and sew, and all those artificial flowers and baubles, might be leftover Depression-era thinking: never throw anything away, you might need it someday.

Stella is very much alive at 104. She forgets to say please and thank you, which is charming, actually, in an earned-the-right sort of way. She is doing the same voluntary self-quarantine today that she did in 1918. Her life is bookended by two worldwide pandemics, each a threat to personal and public health and economic vitality. She doesn’t remember the Spanish flu. She doesn’t remember a lot of things. But just ask her about growing up in Tremont. ■

Jennifer Winegardner is from Cleveland’s west side, went to college on the east side, and law school downtown. She was the editor of the Florida Bar Journal and clerked for the Florida Supreme Court. She’s taken workshops with Dani Shapiro and Marion Roach Smith and sometimes blogs at Winegardner Law.

Cover image: a photo of the author and her grandmother. Photo courtesy Jennifer Windegardner.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.