Cougars are making a comeback. The iconic wildcat hasn’t had a breeding population in the Great Lakes states since the early 1900s, but now they’re moving east. Experts say they could be back soon. Some people swear they already are.

By Patrick Shea

The following story is adapted from an episode of Points North, a narrative podcast about the land, water, and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. Listen to more episodes at pointsnorthpodcast.org.

The small town of Hillsboro sits at the bottom of a valley, surrounded by steep wooded hills. It’s probably not what comes to mind when you think of southern Wisconsin. These woods are scattered with boulders, cliffs and caves.

Growing up in Hillsboro, this terrain was Steve Stanek’s playground.

“Back when I was a kid, there was no such thing as no trespassing. You could go anywhere you wanted to – out in the country, or the woods and the hills,” Stanek said. “There’s a large bluff that towers above Hillsboro. It didn’t really have a name, but we called it Spook Bluff.”

One day, when Steve was 13, he and some friends were exploring the woods on top of Spook Bluff.

“We came down off one side of it and stopped at a farm to get a drink of water, and this enormous roar came out of the woods,” Stanek said. “It was loud, it was throaty, you know; deep.”

Unsure what he had just heard, Stanek hurried home, a little shook up.

Twenty years later, he was working as a reporter at a local newspaper.

“One of our type-setters…had seen a large tan cougar on her property,” Stanek said. “That was the first one. And when you hear of one, you become aware of another and another and another.”

Once he asked around, the local sightings started flooding in – and haven’t stopped since. He’s been on the cougar beat for over 30 years now.

“I’ve published over the years probably about 200 sightings,” said Stanek. “I would say over 50% of them were black.”

The thing is, a black cougar has never been documented by wildlife biologists anywhere.

“There’s no such thing as a black cougar,” said Stanek. “They don’t exist. But are they here? Yes.”

There are things we see and hear, and then there are the things that science can confirm. This is a story about the tug-of-war between them, and how that tension might make it harder to find the truth.

WISCONSIN’S BLACK CAT CAPITAL

“Hidden gem” is a term so overused that it’s sort of lost its meaning. But I can’t think of a better way to describe the Driftless Area.

During the last ice age, a chunk of land about the size of West Virginia was missed by the glaciers that leveled the rest of the Midwest. So instead of the flat farmland you’d expect, there are rocky bluffs and huge hills. As a flatlander, I’d call them borderline mountains.

That’s why Steve Stanek thinks it’s a perfect place for wildcats.

“There’s plenty of places for these things to build dens and to hide,” Stanek said. “To me there’s no mystery about this at all,” said Stanek. “I think they’re year-round residents here, and have always been. I think there’s tons of evidence here.”

Steve wanted to show me that evidence. First stop: Sue Wallace, who says she saw a black cougar right in her driveway a couple years ago. So, we went for a drive.

Perfect habitat for a mountain lion? Wooded bluffs like this one south of Hillsboro, WI, can be found throughout the Driftless Area. (Patrick Shea / Points North)

It was strangely warm – a rainy day in the middle of January. The melting snow turned to fog that seemed to get tangled in the treetops. It was the kind of day when you’d expect to see something mysterious.

Steve told me Sue was a little nervous about being recorded. That’s natural. But she agreed, probably because Steve is here. Everywhere we went, he got a warm reception. People are glad he’s reporting on these sightings, because they’re looking for an explanation.

A lot of folks say they’ve seen these big black cats. And as we drove down a backroad winding through the hills, I peered into the fog and I saw one, too.

We pulled over for a closer look at a wooden cutout of a huge black cat, displayed along the side of an old, white barn – a la bigfoot.

“It shows you how there’s the notoriety of this area, especially this valley,” Stanek said. “There’s been so many sightings here.”

We turned onto Sue Wallace’s dirt driveway, which runs up the middle of a ravine with wooded slopes rising up from both sides of the two-track.

Wallace has lived in Hillsboro her whole life. She’s lived at this beautiful spot west of town for eight years, along with her husband, kids, cats, dogs, and some donkeys. Sue said a few months ago, her husband noticed the donkeys getting really riled up about something in the woods. She has a guess at what it was.

Because one November morning, before sunrise, Wallace saw something she’ll never forget.

“The truck was parked up there in between the two sheds, and then I backed it up down up on the driveway and [came] down here,” said Wallace. “And then it just walked right in front of my headlights.”

Wallace said a huge black cat slipped silently down the driveway, didn’t even glance at her, and disappeared into the darkness.

“His tail just, you know, it swooped like this,” said Wallace, making an upward curving motion with her hand. “It was a long tail; kind of a long body, decently sized.”

“The dog that we had in the house was 120 pounds, and I thought for a quick second it might have been him,” Wallace said. “But then you see the tail on that lion … I ended up sitting in the truck for about 10 minutes before I got out to come in the house. It was pretty scary. Kind of cool though, too.”

THE COUGAR BEAT

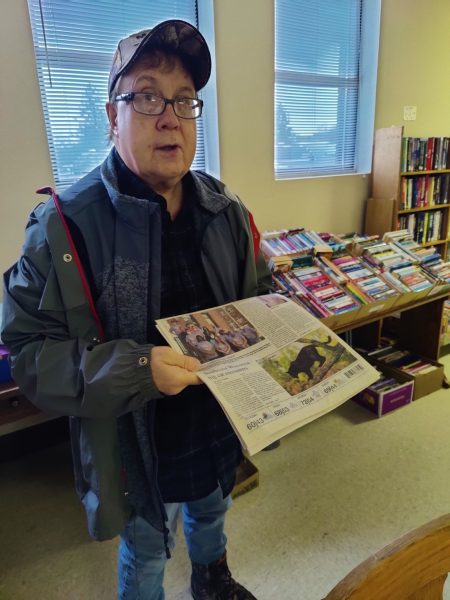

Stanek said Sue Wallace is just one of hundreds of eyewitnesses near Hillsboro. At a nearby library, we head to the basement where they keep archived newspapers. Steve pulls out a series of articles from his 30 years of reporting on cougar sightings.

“8 PM on the last day of May, 1993, while doing chores on their farm…”

“About 40 yards away I saw this big black cat, he reported. The creature was huge…”

“John compared the size of the lion to a large dog and said it was stone black…”

“I stepped out of the barn and here was this beautiful black, glistening animal, Joanne revealed…

“Johnson dashed into his garage to grab his cell phone for photographic proof ‘By the time I got back out, it was gone,’ he said. ‘I could hear it bounding away through the woods to the southeast.

Steve Stanek says he’s reported on over 200 wildcat sightings in local newspapers – with over half the eyewitnesses describing a large, black cat. (Patrick Shea / Points North)

Now remember – scientists have never documented a black mountain lion. So as Stanek published sighting after sighting, he wondered what kind of cats these really were. He thought back to when he was 13, and heard that roar from the woods near Spook Bluff.

“I could describe it exactly, because the next time I heard it was my folks took us to the circus in Madison,” Stanek said. “And it was an African Lion. It was the same roar.”

Mountain lions – also called pumas, cougars, or catamounts – don’t roar. They usually don’t make much sound at all, but when they do it’s a sort of screech.

In fact, there’s only one wildcat native to the western hemisphere that roars at all.

“And that’s a jaguar,” Stanek said. “And a jaguar would explain a lot.”

CRYPTID CATS

Jaguars are in the same family as cougars, but a different genus: Panthera. Experts say they can have a melanistic phase – meaning the jet-black fur that people are describing near Hillsboro.

Stanek believes jaguars and cougars started mating, and have hybridized in the Driftless Area. And even though the closest known jaguar population is in Mexico, he doesn’t need something to officially exist to know it’s there.

“I don’t know if you’re familiar with the term cryptozoology,” Stanek said. “I’m familiar with a lot of that stuff. It’s the study of possibly unknown or out-of-place animals.”

Or as one dictionary puts it – “cryptozoology: the study of creatures, such as the Loch Ness monster, whose existence has not been scientifically proven.”

“I don’t know for sure if there’s such a thing as sasquatch or not,” said Stanek. “But the one I give the most credence to are sea serpents.”

Steve said he also had a big flying saucer phase in his younger years, and that his whole jaguar beat comes from that life-long fascination with the unknown or unacknowledged.

But in the Midwest, wildcats bridge the gap between “crypto” and actual zoology.

COUGARS ON THE MOVE

There was a time when “mountain lion” wasn’t really a fitting name for North America’s most iconic wildcat. Cougars once lived all over the continent; not just in the mountains out west.

But like so many other large predators, they were hunted aggressively starting in the 1800s and eradicated from most of the country. There hasn’t been a breeding population in the Great Lakes region since the early 1900s, according to wildlife officials.

This mountain lion, photographed in late December, was Wisconsin’s 15th confirmed sighting in 2022. (Wisconsin DNR)

But cougars are making a comeback. Slowly but surely, they’re coming down from the mountains and moving east again. There’s a breeding population back in the Dakotas and Nebraska after being gone for a century.

And even the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has confirmed fifteen cougar sightings over the past year. Six of those were in the Driftless Area – not too far from Hillsboro. All of them tan, by the way.

The department says those were all male cougars that walked more than 800 miles from South Dakota.

These animals are very territorial – especially males – and they will travel huge distances in search of a mate. The DNR says they won’t find one here, but how are the cougars supposed to know that?

You probably wouldn’t know if you’re seeing a male or female cougar at first glance. Researchers find that out later, with DNA samples from scat or deer carcasses. But you’d think you’d be able to tell what color it is.

It was still dark that morning when the alleged cougar crossed Sue Wallace’s driveway, but she’s sure of what she saw.

“It was the black one,” Wallace said. “I mean, he walked right in front of my headlights of the truck. I could definitely see what it was.”

Despite all the eyewitness accounts, the Wisconsin DNR stands firm in its position: there’s no evidence of black cougars in the state. But Stanek thinks state officials know more than they’re letting on about.

“The only thing that makes a mystery out of these animals being here is the DNR,” Stanek said. “I believe they’ve live-collared the black ones, along with the tan ones, and released them with radio transmitters.”

I pressed Stanek on what the motivation would be for this secretive monitoring. He had a theory for that.

“It’s because they don’t want to reserve timberland,” Stanek said. “Because if this is confirmed that it was an endangered resource, they would have to set land aside.”

“I don’t know where exactly that stems from,” said Randy Johnson, a large carnivore specialist with the Wisconsin DNR. “I think it’s probably a bigger issue of mistrust of government and conspiracy, that type of thing. But what I can say is obviously there’s no cover up underway. We work really hard, in fact, to share this information.”

The DNR has a website dedicated to cougar sightings. There are photos, a map of where the sightings were, a timeline of the DNR’s response, and a place to file your own report.

“So, there’s really no cover up when we have a web page dedicated to sharing information on them,” Johnson said.

When it comes to the black cougars, Johnson was actually careful not to rule it out entirely.

“I think scientifically speaking, there’s no reason to think it’s not possible,” Johnson said, adding that the lack of any official documentation makes him dubious.

“It’s never been documented in hunting records; it’s never been documented through photographs. There’s no evidence of ever having a black phase mountain lion,” Johnson said. “However, I think it is possible because there’s several species of cats that have a black phase. Never say never, right?”

THE EYES DECEIVE

While Hillsboro seems to be a hotspot for alleged black cougar sightings, they’re not limited to just Wisconsin.

In August 2022, someone got a photograph of the black feline creature in Copemish, Michigan. It went viral from there.

DNR officials went to the location with the photographer who took the shots of the black cat. They reenacted the pictures for perspective, placing an item where the cat was spotted. With the data they collected, officials came to the conclusion it was just a housecat, 20-30 inches long.

Despite all the hype, there’s still no hard evidence of a black cougar anywhere. And in Michigan, just like Wisconsin, there’s been no evidence of a breeding population of even the verified tan cougars since the early 1900s.

But that doesn’t mean people stopped seeing them here, either.

“My mom says she saw one, my uncle claims he saw one. But, you know, we just never had any solid evidence,” said Brian Roell.

Roell is a lifelong Michigander who’s now a wildlife biologist, and part of the DNR’s cougar team.

“Any sighting that comes in, that whole team reviews it,” Roell said. “And in order for us to call it a confirmed sighting, we have to have a unanimous decision.”

A mountain lion captured on a trail camera near Cassville, WI. (Wisconsin DNR)

“So, we’ll actually google cougar pictures, you know, ‘cougar next to road’ and just do a global search,” Roell said. “And then all of a sudden you’re like, ‘hey, that’s the same picture.”

Since the cougar team’s first year in 2008, the number of confirmed sightings has been trending up. And that doesn’t necessarily mean there are more cougars; just more sightings.

“I know one thing that has really probably increased our sighting rate is the availability and the use of trail cameras,” Roell said. “They are just everywhere out in the woods. Geez, now they’ve got ‘em where they send pictures to your cell phone.”

When the cougar team gets a picture that seems promising, they follow up in the field. Most of the team members have traveled to New Mexico and other western states to get trained in tracking these cats. They studied paw prints, scat, and the physical characteristics that separate cougars from animals often mistaken for them.

“I mean, there are a lot of domestic cats that get submitted as mountain lions, Roell said. “We’ve had a calico even one time. I was like, ‘All right now…you know, they do not come in calico.’ And by and large, most of those are people that honestly, truly believe they saw a cougar.”

There are two different kinds of knowing when it comes to these wildcat sightings. There are eyewitness accounts, of which there’s no shortage, and then there’s the much smaller pool of sightings confirmed by scientists – with DNA proof, or an unmistakable set of tracks. Different people value these kinds of knowing differently.

But Roell says it’s important for the experts to hear folks out. The cougar team tries to be as transparent as possible in their interactions with eyewitnesses. But there’s another kind of report that’s muddying the water.

“It’s one of the weird things that with all our other wildlife sightings, we don’t get people doing hoaxes. But with mountain lions, we do,” Roell said. “Submitting pictures from other states, we’ve had mounted cats placed out in the woods before; I know Wisconsin has had the same scenario, so, it’s kind of strange.”

One incident that stands out to Roell is when a woman in the Upper Peninsula sent in a picture of a cougar, which she says she took from her car.

“She had a young daughter in her car with her, and her young daughter collaborated the story as well,” Roell said.

“Yet, what we found out was that the picture was actually shot in Louisiana and was flipped just using Photoshop or whatever. They just inverted the picture and turned the cougar the other way. It just shocked me that she, one, went to that effort but then actually involved her young child in the hoax.”

Roell said that’s just one of many attempted hoaxes. He’s seen cases where people made their own tracks with their thumb. And after the Louisiana photo hoax, he always makes sure to do a thorough internet search before going any further with a reported sighting.

“So, we’ll actually Google cougar pictures, you know, ‘Cougar next to road’ and just do a global search,” Roell said. “And then all of a sudden, you’re like, ‘Hey, that’s the same picture.’”

THE COST OF FALSE SIGHTINGS

Roell said he’s not sure why someone would do this and neither am I. Sometimes people can be mysterious, too.

But as far as the misidentified sightings, I can see how that might happen. Except maybe the calico.

Over the past few weeks, working on this story, I’ve become pretty obsessed with mountain lions. If something large and feline darted across the road in front of my headlights, I could see myself coming to the cougar conclusion. Seriously. And so many people do. Roell said his team reviews around 250 sightings per year, but have only ever confirmed 89 ever.

Hillsboro, WI is a hotspot for reported black cougar sightings – an animal never documented by wildlife officials. (Patrick Shea / Points North)

I came into this with a lighthearted story in mind and it is, for the most part. But this deluge of false reports that biologists have to sift through – that takes time. And time is a limited resource. In fact, some of Roell’s bosses don’t think it’s worth it.

“We’re getting pressure not to confirm mountain lions to the extent that we currently do,” Roell said. “We’re having a meeting with the cougar team and with some folks from Lansing to say, ‘Is this worth our effort to continue to go through this level of detail?’ In my mind, the answer is yes, but I may get overruled on that.”

The less trust there is between the experts studying these cats and the folks reporting sightings, the harder it is to keep track of the cougar’s expanding range. Roell said it’s best when eyewitnesses and scientists work together.

Because a time could come in the not-so-distant future when they could be tracking the true return of cougars to the Midwest.

“We certainly have the habitat to sustain a few mountain lions; I don’t think we’re ever going to have a really robust population just because they have super large territories,” Roell said. “But I think it certainly is in the realm of possibilities.”

With a creature as elusive as a mountain lion, it’s never easy to definitively say where they are, or where they’re going. For now, they live somewhere in this foggy land between myth and migration.

This story was adapted from an episode of Points North, a narrative podcast about the land, water, and inhabitants of the upper Great Lakes. Listen to more episodes at pointsnorthpodcast.org.