In nineteenth-century upstate New York, demons came knocking.

By Ed Simon

In the United States, the fervent evangelical revivals of the Second Great Awakening that burnt across the frontier during the first few decades of the nineteenth century resulted in the emergence of new sects, including the Seventh Day Adventists, the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the Mormons, with one of the most unusual groups being the loose affiliation of vaguely Christian gatherings known as Spiritualism. Combining a belief in the occult with Yankee Protestantism, and promoting the holding of seances, the uses of divination, and the manipulation of strange symbols, the Spiritualists emerged in upstate New York in 1848 when a trio of young girls known as the Fox Sisters claimed that they had made contact with spirits in another world, though the series of knocks, pops, and bangs that the specters used to communicate turned out to be an elaborate hoax concocted by the siblings. Despite that, Spiritualist adherents held a hope that the occult could supplement traditional religious faith, and that it could be placed on a scientific footing for explaining esoteric phenomena. Spiritualist speakers like the medium and proto-feminist Cora L.V. Scott and Paschal Beverly Randolph, a free Black man who introduced Rosicrucianism to America, lectured throughout the United States, holding forth on topics like the European occultists Emanuel Swedenborg and the scientist Franz Mesmer, an early researcher on hypnosis.

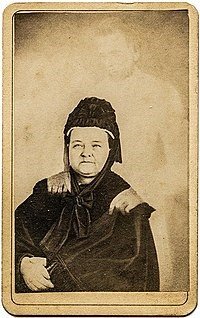

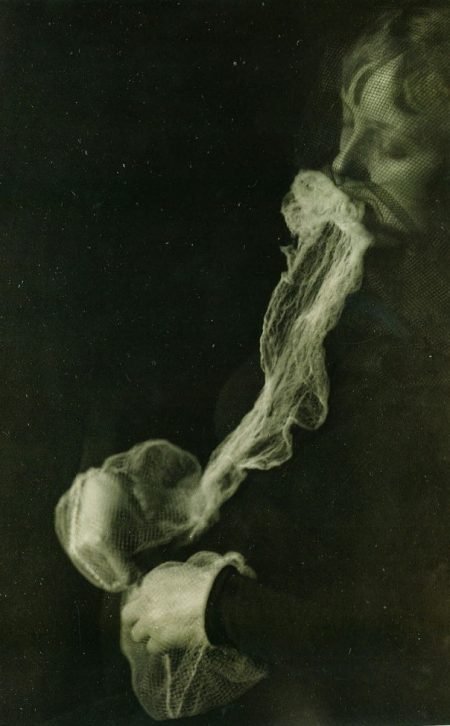

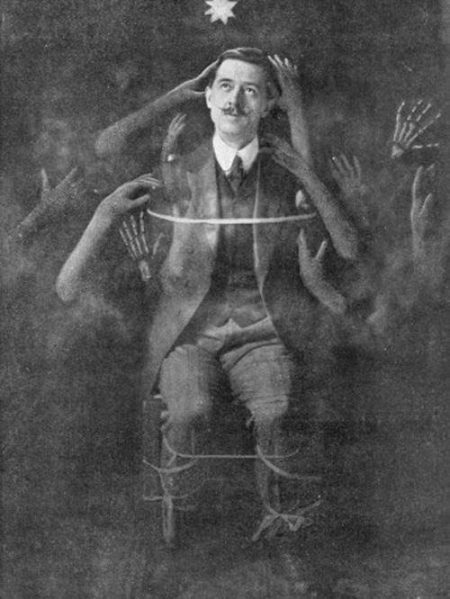

Spiritualists were innovative in term of using modern technology like photography to (depending on your perspective) either provide visual evidence of the spirit realm or to huckster gullible believers. Top to bottom, left to right – a photograph of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln taken in 1869 by the medium William H. Mumler, with her husband President Abraham Lincoln a ghostly presence over her shoulder; a séance held in 1898 Paris with the Italian medium Eusepia Palladino, and featuring an “orb” specter in the mirror; the medium Stanislawa Popielska producing ectoplasm, a type of spectral lifeforce, as photographed by the German parapsychologist Albert von Schrenck-Notzing in 1913; and the British magician William S. Merrit, a popular debunker of spirt photography, with an admittedly hoaxed example of the form displaying hellish hands grasping at him from the ether. While the vast majority of “spirit photographs” seem amateurish, self-evident forgeries today, the most proficient (particularly those featuring ectoplasm) are still disquieting. Deception or authenticity weren’t the only explanations for the provenance of spirit photographs, of course, with the 1866 Second Plenary Council of Baltimore, a gathering of American Catholic bishops, concluding that “There is little reason to doubt that some of the phenomena of spiritism are the work of Satan.”

While some Spiritualists were con artists and grifters, the movement itself could be shockingly enlightened, advocating for radical positions concerning abolition and suffrage. “The standard-bearers of the American occult took a different path,” from their European antecedents, writes Mitch Horowitz in Occult America: White House Séances, Ouija Circles, Masons, and the Secret History of our Nation. “They sought to remake mystical ideas as tools of public good and self-help.” At its core, however, what defined Spiritualism was the same thing that distinguished European esotericism: a belief that the profane world was a dim reflection of a transcendent and sacred one, and that as it is here so it is above, as it is here, so as it is below. Matter can only be understood in terms of the spirit, so that as Scott said, “when the physical scientist declares that he has discovered the process of creation, he omits the one power of creation that alone is capable of solving the mystery.” Conventional ministers rejected as either hoax or demonic manifestation the spirit visitations and the communication with the dead that Spiritualism championed, but Spiritualists themselves also had something to say about demonology, partially drawing from continental occultists like Ephraim Lévi.

Writing in Ghosts of Futures Past: Spiritualism and the Cultural Politics of Nineteenth-Century America, Molly McGarry observes that “Spiritualists understood witchcraft as a sister belief, a past manifestation of otherworldly power, born of an American culture more likely to persecute messengers than to attend to sacred signs.” Spiritualists may have believed that the individual beings who were interpreted as demons in previous centuries were real, but they also thought that they had been misnamed. Writing not of the Spiritualists, but of their European occult contemporaries, Jeffrey Burton Russell note in Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World that their “admiration for Satan was not Satanism, however—not the worship of evil—for they made the Devil the symbol of what they regarded as good.” Satan had less of a role in American Spiritualism, but in the same way that Lévi and his associates rehabilitated the idea of Satan—redefining something like Baphomet as a symbol of good—so too did the Spiritualists reconfigure phenomenon like demonic possession as actually being a medium’s connection with specters from the afterlife.

This is an excerpt from Pandemonium: A Visual History of Demonology.

Ed Simon is the editor of Belt Magazine.