“If you lived up here, you’d know what it was. It’s all anyone talks about. You’re either for it: it’s going to create jobs. Or you’re against it: it’s bad for the environment. No one’s neutral.”

By Sharon Dilworth

The following is an excerpt from Sharon Dilworth’s To Be Marquette released by Carnegie Mellon University Press.

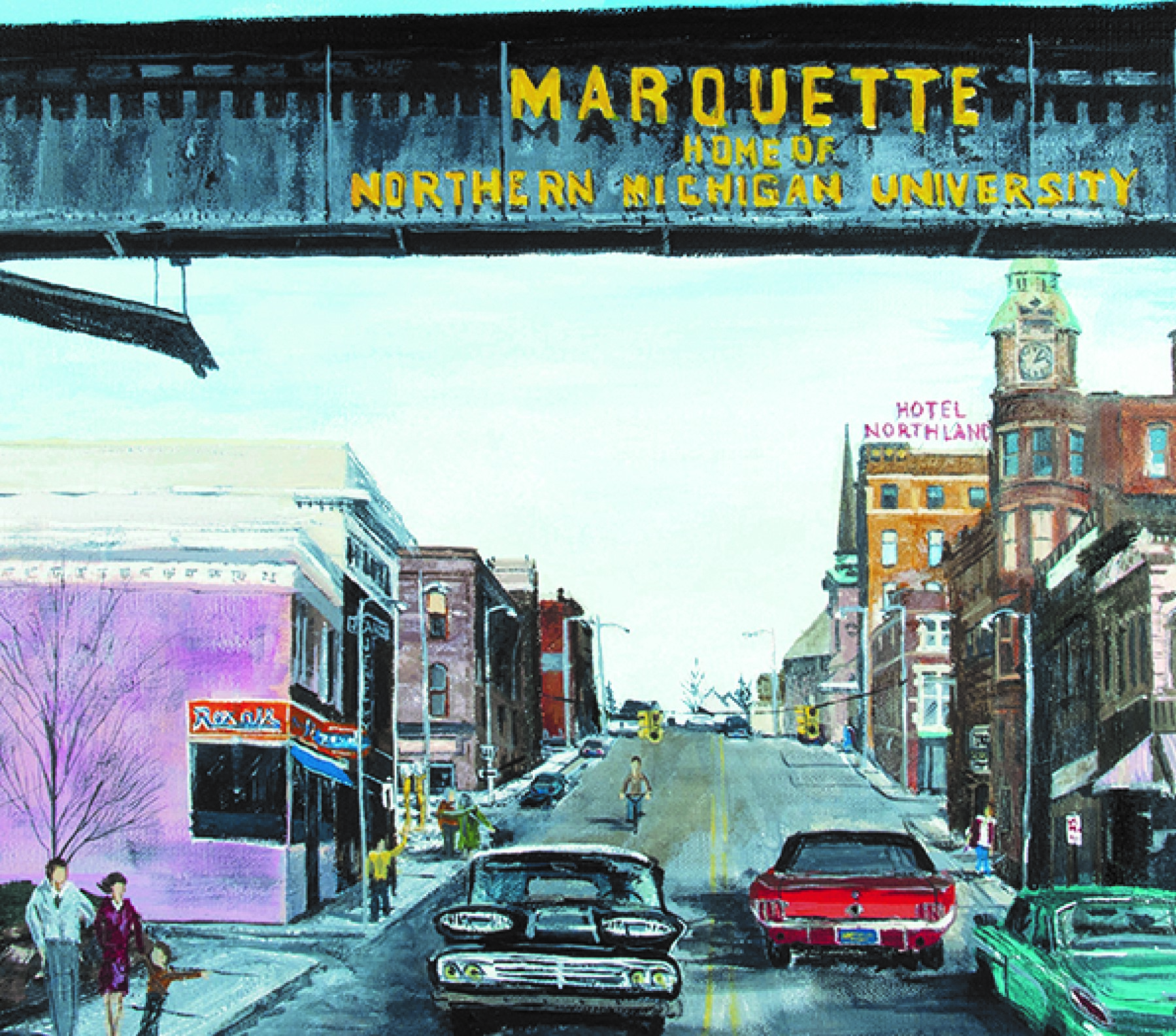

I think it was then that I began to think of Marquette as a verb—to be Marquette was to be rid of the person I had been and to embrace someone completely different. Up there, everything seemed possible. In Marquette, it was possible to live that close to the natural world—to live that close to beauty.

Project Seafarer, later known as Project ELF, was a top secret government-funded project created during the Cold War in the 1970s that allowed the military to communicate with submarines anywhere in the world, using extremely low frequency radio waves, aka ELF. The short coded, ultra-classified messages were to be used in extreme emergencies, such as a nuclear attack. The first communications lines covered eighty-four miles across Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Plans to develop the project included miles more lines, all of which were to be embedded in the bedrock across a wide swath of the state’s northern wilderness.

1

That first year in Marquette, the ecology studies midterm was in October on Presque Isle Park, a few miles north of campus.

Snow fell. There was no accumulation, but light flakes swirled overhead.

It was a practicum, not something I had done before. We were being tested on our ability to identify the foliage and wildlife of northern Michigan. Dr. Robinson had set it up like a fitness course. Each station had a sample of something we were supposed to identify. We were going out one by one. I was scheduled to go last, right behind Shane.

We were waiting at the burial site of Chief Kawbawgam, the Ojibwa chief, who I knew had lived in three different centuries, from 1799 to 1902. His wife was buried beside him. The sign did not say how long she had lived.

The grave was marked by an enormous white glacial boulder, which had been touched so many times the surface was more like glass than stone. The guys would usually end up sitting on it, until Dr. Robinson reminded them that it was a grave and not a park bench.

Some of the guys finished before half the group had even started. They were winded. They had run the course, and now I would have to do the same. We were competitive like that.

They were talking, all at once. The noise was distracting.

“Careful,” Dr. Robinson said. “I’ll consider any chatter cheating. I want to know what you know, not what your friends know.”

I was nervous, which was stupid. It was just a test, in a class I loved. Plus, I had been studying all week.

My turn. I headed out, notebook in hand, with the miniature pen pushed down into the coil spirals.

It wasn’t hard. I knew the three kinds of conifers: pine, fir, and spruce. The white pine had five needles per cluster; the Scotch pine only had two. The Lombardy poplar tree was next. I knew we’d get tested on that. It was local, and Dr. Robinson pointed it out every time we passed it on the road out to Presque Isle.

It was quiet. The snow had stopped.

There was a shift in the woods, and I felt suddenly alone—isolated from the rest of the class, as if they had all gone home and left me.

I knew I was taking too long. I got flustered trying to hurry. The next station was a white birch bark, which didn’t seem right. I had already identified that. I wondered if I had gotten turned around and was backtracking my steps. The path was thick with pine needles, and there were no footprints. I took the next right. The path narrowed, almost disappearing.

I knew Presque Isle. We had been coming out every week since school started. I knew that I should be able to see the lake; it was visible from almost everywhere on the island. But I was deep in the woods and saw nothing but the canopy of trees, the ferns, and the pinecones at my feet.

Something wasn’t right. The woods hushed. I felt the shadows of the cloud-filled day.

So I started to run, hoping I wasn’t missing a station. If I could get Lake Superior in sight, I would be okay. I kept moving. Dr. Robinson was going out after me to collect the test samples, and I hurried so he wouldn’t overtake me. I was taking way too much time.

Then there it was. The huge expanse and the open water. Lake Superior was in sight. Relief. I was right where I should be.

But just as fast, there was something on the ground, something that shouldn’t have been there. I couldn’t stop. I went down. I hit the ground—smacking into the hard earth.

I felt the blood in my throat, like my teeth were falling out. I closed my eyes and held them shut tight, trying to make the pain go away.

I heard people. The guys were there, so I must have cried out. I was that close to finishing the course.

They said my name, over and over, like a birdcall, where there are no pauses. “Molly! Molly! Molly!”

“Are you alright?”

“Can you talk?”

“Say something.”

I swallowed carefully, worried I was swallowing teeth. The blood filled my throat. I did not want to cry in front of the guys, but the minute I tried to speak, the sobs took over. Loud, rasping sobs and I couldn’t stop. Dr. Robinson was yelling at them to hurry.

They helped me up. My jeans had ripped at the knee. Cold air against my bare skin.

The guys walked me over to Dr. Robinson. He was in the Jeep, the engine running. I tried to say that I was okay, but I really didn’t feel that great, and he drove us down Lakeshore Drive way over the speed limit.

My mind raced. I knew what I had seen. I knew exactly what I had tripped over.

A dark brown stake. Metal. Right in the middle of the path, deliberately, so that I would fall.

It was Shane.

It had to be him because that’s how I thought back then. Everything was about me. I didn’t even consider another option—that it could have been about something else. Or that the stake wasn’t Shane’s revenge. I saw what I saw. I knew what I knew, and I believed what I believed, without considering anything else.

Ever since the night of the bonfire, when I had laughed at him, he had been out for blood. Now it seemed he had gotten what he wanted.

A large gash on my chin. I bled all the way to the hospital, secure in the belief that how I saw the world was the way it was.

End of story.

now

It’s funny what you remember. What you don’t.

When I called Charlie to ask him about that first year in Marquette, he laughed. “Are you asking about the weed?”

I hadn’t been.

“Isn’t that what you want to know? How we got it up there? Because we sure as shit didn’t drive down to Detroit every week.”

Charlie had a brain tumor a few years ago. He’s out of danger now, but he’s lost the logic of a conversation that makes sense to both people having it. When you talk to him, you can see the dark crevices of memory loss moving around as if you’re in a maze.

“We were always high on something.”

That was probably true.

“Dr. Robinson,” I said.

The line went quiet. I thought he had hung up. Then the sound of a barking dog.

“Our guru?” he asked finally.

Charlie was in the Pacific Northwest, living in an RV park with a woman who raised chickens and grew her own vegetables. They were only a few miles from the ocean. He had sent me photographs of the peacocks that wandered onto their property. “How do you think they got here?” he had asked.

I didn’t want to talk about his animal farm, so I asked him again about Dr. Robinson.

“That’s a blast from the past,” Charlie said.

“You ever hear from him?” I asked.

“Mr. Nature Man?” Charlie asked. “The Grizzly Adams for the new generation? Our hero who we put on that fern-strewn pedestal? He who knew all the things we wanted to know.”

I wouldn’t have argued against those descriptions. That’s who he was.

“You know where he is? Or heard anything about him lately?”

Dr. Robinson had disappeared—he had left Marquette at the end of our freshman year. Never to return.

“Doc Robinson. Charismatic leader of the lost souls and polluted planet? Looked like a movie star, all that hair and blue eyes, those crazy muscles like he could deadlift a cow. He had that scar on his upper lip. Remember the rumors? That it was from a bear he ran across in the woods. Not sure that was ever proved. Used to make us work on graph paper. We had to buy special notebooks.”

Things I had forgotten.

Not what Dr. Robinson looked like. But I had forgotten the scar. I had forgotten the bear story. I only remembered then that we had used graph paper notebooks. It made us feel like real scientists, and when needed, we could draw graphs and diagrams without needing a straight edge.

I could hear Charlie dragging on a cigarette through the phone. When I asked, he told me he had quit smoking years ago.

“The good doctor hated being inside. Couldn’t stand buildings. Another rumor, most likely not true, was that he was the son of some wild animal. A panther or a coyote. We used to wonder if he lived in a tent somewhere in those woods.”

There were things I needed to know. Things I needed to understand.

“Project ELF,” I said. “What do you remember about that?”

“Haven’t heard those words in years,” Charlie said. He began to talk about the peacocks again. How they lost their tails and left them behind in the brush.

I had to keep him on track. “So you remember it?”

I was at the lake that afternoon and a guy, someone I didn’t know, started talking to me about ELF—hence the urgency of the phone call to Charlie. It was an odd and disconcerting encounter, especially right after finding the newspaper article in the library. The one that reported on the demonstration we had all been to that first year. A photograph and quotes about how we felt about Project ELF. It got my mind reeling, and I was suddenly unsettled, without knowing what to do, who to talk to about it.

“Our raison d’etre? The thing that made us feel useful. Like we were really doing something worthwhile. Us fighting the powers that be.”

“But wasn’t it?” I asked.

Charlie might have forgotten, but all those protests, the demonstrations, the fights—they were a big deal.

“I’m not sure,” Charlie said. “I do know that’s what you and the other goofs wanted it to be.”

“All those demonstrations, all those protests,” I said. “It had to be something.”

It was something. He was misremembering.

“Think about it—every time anyone talked about it, they always said it was top secret. Every newspaper article described it that way.”

“So?”

“So if it was so top secret, how did we all know about it?”

Charlie lit another cigarette. He smoked a lot for someone who had quit. “Only the male of the species is called a peacock. The females are called peahens. A group of peacocks is an ostentation. A group of females is usually referred to as a bunch of peahens.”

I didn’t think the U.S. government simply gave up on projects. Especially ones that had to do with defense. I didn’t think Charlie did either. It was hard to tell if he was being deliberately evasive or if he didn’t know what happened to Project ELF. It had been years.

“I’d rather be an ostentation than a bunch of peahens,” Charlie said.

He was neither.

“So tell me: what happened to it?” I asked. “This is important.”

“We mailed it to ourselves. To a post office box in Marquette. They had no idea what was in the packages we picked up every month. Humboldt Gold. Straight from Northern California.” Charlie went off, talking about his failed weed business. “No one up there had any money. And if they did, they spent it on Mad Dog 20/20 and scratch-off lottery tickets.”

The dog’s barking was louder now. Like Charlie was holding the phone close on purpose.

“We should have been paying attention,” Charlie said. “But we were too dumb.”

“To what?” I asked. “What should we have been paying attention to?”

Then someone yelling. His girlfriend telling him to get off the phone.

He had to go. “I’ll be in touch.”

I had so much more I wanted to ask him.

Later that week, he emailed me. You were in love with him.

I wrote back. I liked him. He was the best professor I ever had, but I was never in love with Dr. Robinson.

It was 3 a.m. on the West Coast, but he answered immediately. The subject line: I wasn’t talking about the good doctor.

A second email. Go find out what happened. I’m not much help. Too many holes in my head. It feels important. Even now.

2

Dr. Robinson talked about Project ELF as if we all knew what it was and as if we all understood why it would be so bad for the region, even though the military said just the opposite.

I had never heard of it but soon realized I was the only one who didn’t understand what it was. The others all knew about it. They had opinions on ELF and expressed them with anger, almost outrage. I felt left out.

“It’s because you’re from Detroit,” Finley told me when I asked him to explain it. “If you lived up here, you’d know what it was. It’s all anyone talks about. You’re either for it: it’s going to create jobs. Or you’re against it: it’s bad for the environment. No one’s neutral.”

“So, you think it’s a bad idea, right?” I asked, hoping he would explain why it wasn’t good for the environment. That was only one of the things I didn’t get from the class discussion.

“Me?” Finley asked.

“You agree with Dr. Robinson? You think we should fight it?”

“I’m kind of on the fence.”

“I thought you said no one was undecided.”

“I might be the only one,” he said.

He turned to me and smiled. He looked odd, and I realized he was the sort of person who rarely smiled. He worried a lot.

“I may be the only person in the whole world who can see both sides.”

He had long bangs that covered his eyes unless he moved them aside. He told me once that his head was too big for his body and that when he was younger the kids had called him Giant Head. “You must have grown,” I had said.

He was cute when he smiled. I told him that.

“You too,” he said, which felt awkward.

He took me over to the university library, back to where they kept the periodicals. There were comfy chairs, low tables, and lamps—like someone’s living room. It was my favorite place to be on campus. It was usually crowded, students asleep, others reading, so I wasn’t the only one who admired it.

There was an enormous window back there that overlooked a copse of enormously tall pine trees. I read some of the articles Finley had collected and understood the controversy a bit more, mostly by reading the letters to the editor in The Mining Journal. Finley had been right about that. Every other letter was for it; the rest were dead set against it.

I stared out the window and watched the wind bend the trees. It was a small grove of white pines. I knew that now. I knew that their needles grew in groups of five and that the tallest white pine tree in Michigan was 143 feet tall, but I couldn’t remember where it was.

I tried to read more about Project ELF. I had a hard time getting past the name. I couldn’t be the only one who, every time someone said it, thought of Christmas. Project ELF seemed like it would be festive, like there would be presents and decorated trees. It didn’t sound harmful or dangerous or end-of-the-worldish. I saw Lake Superior and heard about the harm ELF would cause to the entire region. Beauty and danger. But it didn’t connect for me.

–From MHUGL

(Military History of the Upper Great Lakes)

Since soon after the close of WWII and the development and widespread proliferation of nuclear weapons, it became clear that the only way to avoid a third world war and the subsequent destruction of the entire planet by nuclear annihilation was to practice extensive nuclear deterrence. Nuclear deterrence follows the assertion that no country would dare strike another with nuclear weapons while they knew that country could score a major retaliatory strike. This makes the survivability of a country’s nuclear capabilities of utmost concern. Any capability that can be easily taken out at the beginning of a nuclear conflict does not contribute to that nation’s nuclear deterrence, as it does not contribute to the country’s ability to perform a retaliatory strike.

Ballistic missile submarines were, and are still, considered some of the United States’ most survivable nuclear assets, as the enemy ought never to know where they are, to be able to destroy them. Land-based assets are much more easily detectable, either by intelligence agents working domestically or by satellite surveillance.

In order for the submarine to contribute as much as possible to the nation’s nuclear deterrence, it must be able to stay in constant communication with National Command Authority (NCA). They are the only people who can release nuclear weapons. That is the president and the secretary of defense, or their successors. This is commonly referred to as command and control. Otherwise, even in the event of unrestricted nuclear warfare, the weapons aboard will remain dormant. Before the advent of ELF technology, the vessel would have to regularly surface or, at best, deploy a buoy near the surface, exponentially increasing its likelihood of being detected and/or severely restricting its mobility. As spotted submarines no longer contribute substantially to the nation’s nuclear deterrence, it quickly became imperative to invent methods of communication that limit or remove entirely the effect of communication on the vessel’s detectability.

Stated in a briefing on the ELF communications system, by the office of Capt. Ronald L. Koontz, USN, the program manager for ELF communications, the mission of a ballistic missile submarine has three main objectives, as follows: “Remain undetected, maintain continuous communications reception, and maintain a condition of readiness that will ensure successful launch of all missiles if and when directed by NCA.” The development of an ELF communications system helps these vessels accomplish all three parts of that mission, nearly anywhere in the world.

Sharon Dilworth is an award-winning fiction writer. She’s the author of three short story books including Year of the Ginkgo, Women Drinking Benedictine, and The Long White. Her work is also featured in the collection of short stories, Here: Women Writing on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. She is the recipient of numerous awards including the Iowa Award in Short Fiction, a National Endowment for the Arts Grant, a Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Grant, a Pushcart Prize in Fiction, and a Hopwood Award. Currently, Sharon lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where she is the Director of Carnegie Mellon University’s Creative Writing program.