By Andrew Morton

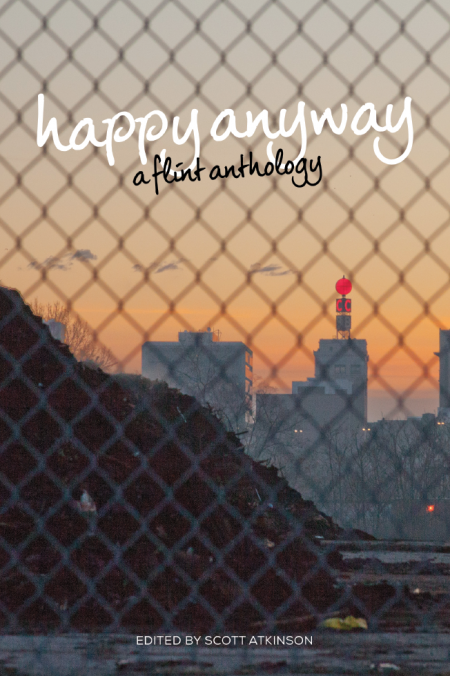

Excerpted from Happy Anyway: The Flint Anthology (Belt Publishing, 2016).

I live in Flint. I own a home in the city. However, I’m still often reluctant to call Flint my home. This isn’t because I’m not madly in love with this place, or incredibly proud to live in the city. It’s because of the way I talk.

As soon as I open my mouth, most people realize I’m clearly not from here. What comes out of my mouth is a sort of transatlantic mess — the result of spending approximately half of my life in the UK where I was born, and the rest in the middle of Michigan, America’s high five.

Whenever I meet new people, either in Flint or elsewhere, as soon as people realize that I’m British and that I live in Flint their first response is usually, “Why?” I’m always puzzled by and slightly amused at the reactions I get. For the most part they always seem to suggest that Flint, Michigan, is clearly not good enough, or fancy enough, for a British person. Obviously this is based on a lot of tired stereotypes of the British, which I blame mostly on PBS.

So how did I end up here? The short version of the story goes like this: my father is an engineer, his company transferred him to Michigan in the mid-nineties, we eventually settled in a suburb of Flint, and in an attempt to assimilate and because my older brother was one, the thirteen-year old me decided to become a skateboarder. We soon learned that there are a lot of cool places to skate in and around downtown Flint, and the rest is history.

That’s also the cooler version of the story. What I left out of the first version is that I was raised in the Salvation Army, and when my family moved to the States we began attending the Salvation Army Flint Citadel Church on Kearsley Street in downtown Flint. This was really my first introduction to the city. At that time, there really wasn’t much happening downtown. The general consensus was that it was a dangerous place, and one that you should avoid at all costs. Most people at the Church would simply drive in for Sunday services and weeknight activities, and then return home to the suburbs or the “nicer” parts of Flint afterwards. However as I gradually began to spend more time exploring the city, I never felt scared when I was downtown. Perhaps it was my youthful naiveté. The more likely reason was the fact that I rarely saw other people — and when I did encounter people downtown, they were usually friendly.

It was at some point during this period that I think Flint first began to get under my skin. After graduating high school I studied theater at the University of Michigan-Flint, located in the heart of downtown. I lived at home for the first couple of years, but then moved into an apartment with some friends in the East Village, a small neighborhood nestled between the UM-Flint campus and the Flint Cultural Center. During the four years I was a student at UM-Flint I taught after-school reading programs at both Cook and King Elementary Schools, both of which — like many of Flint’s other schools — are now closed. For a while I delivered sandwiches and got to know people who worked in the various offices downtown. One summer I helped run a youth employment program through the Michigan Community Service Corps, and during another I helped plant a garden on the corner of Martin Luther King Boulevard and 5th Avenue — the unofficial border between downtown and North Flint.

I’m very protective of this place; I’ll defend it whenever necessary, and I now see how instrumental this city has been in making me the person and artist I am today.

During the four years I studied and worked in Flint, I slowly began to see a different side of America. Growing up in England, my only insight into American culture was what I saw on TV. Just like how many of my American friends based their understanding of British culture from what they watched on PBS, I grew up watching shows like Saved by the Bell and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. When we moved to the US, my family lived in a hotel for almost a month before we found a place to live. My brother and I spent most of those days watching a ridiculous amount of cable television, exploring the mall across the road, and eating out most evenings. We thought it was great. It felt like we were living the life of the characters from our favorite shows. However once I began to experience Flint in new ways, I began to see the other America. The one we never saw on TV growing up in England.

I started college thinking I wanted to be an actor. Four years later I knew that was no longer the case, but I wasn’t certain what I wanted to do instead. But I began to recognize a pattern in a lot of my part-time and summer jobs. They all attempted to address some of the larger social and economic issues facing communities like Flint: illiteracy, poverty, blight. For a while I thought perhaps I would become a teacher or a social worker, but I couldn’t quite give up the idea of wanting to do something in theater. Towards the end of my time at UM-Flint, Judy Rosenthal, an anthropology professor suggested I read Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed. I did, and found what I had been looking for. The thought of creating theater that could highlight the injustices in the world and demand change energized me, and I was hungry for more.

In 2004, I graduated from the University of Michigan-Flint. It was looking fairly certain that George W. Bush was going to be re-elected, and despite my family being well and truly settled in Michigan, I wasn’t too happy with the direction the country was going in. I remember many nights at the Torch Bar & Grill in Buckham Alley — a dive bar still frequented by the members of Flint’s small but faithful theater scene — when friends joked about how they wanted to move to Canada, or England, or anywhere where a Bush wasn’t in power. As I still had my British passport and family back in the U.K., I had an exit strategy, so I took it.

I had also been accepted into a relatively new masters program at Goldsmiths College, part of the University of London. It was a program in Community Arts, designed for artists of various backgrounds who wanted to create work in and with diverse communities, and often outside of the traditional arts sector. So in the summer of 2004 I went back across the pond, and found a new home in South London.

To the surprise of a lot of Americans I met when I first moved to the States, I didn’t grow up in London. I know England is not a big place, but there’s a lot more to it than simply London. I was born in Derby, a mid size city in the Midlands (roughly two hours north of London). When I moved to the big smoke, I knew no one. I found a room to rent in a Victorian Terrace house on a street that overlooked a park that was only a short walk away from the Goldsmiths campus. As I was studying part-time, I found a job folding over-priced T-shirts in an Urban Outfitters on Oxford Street — the busiest shopping street in London. However, it wasn’t very long before that job began to eat away at my soul. I started looking for new work, and to my luck the school across the street from my house, Deptford Park Primary School, was looking for new teaching assistants. I got the job, said goodbye to folding T-shirts, and soon realized that while a part of me had run away from Flint, I had inadvertently found Flint in London.

Deptford Park was a school located in the middle of a large social housing estate — the Pepys Estate, named after the noted seventeenth-century diarist Samuel Pepys. During the time I worked at the school, the estate was the subject of a BBC documentary called The Tower: A Tale of Two Cities. In an attempt to fund regeneration of other parts of the estate, the local council had sold one of the towers (the one with the best views of the Thames) to a private developer. As that tower was redeveloped into luxury apartments, the residents of the rest of the estate struggled with crime, heroin abuse, and many other issues that often plague residents of low-income communities.

I quickly fell in love with this little community and many of the people I met there. The students I worked with reminded me very much of many of the young people I worked with in Flint. They were bright, energetic, and eager to learn. The teachers and other support staff at the school knew that the estate (and the school) had a bad reputation, but they fought hard against this, and worked tirelessly to make the school a safe and supportive environment for everyone there. They too reminded me of many of my friends who I had left behind in Flint.

I quickly fell in love with this little community and many of the people I met there. The students I worked with reminded me very much of many of the young people I worked with in Flint. They were bright, energetic, and eager to learn. The teachers and other support staff at the school knew that the estate (and the school) had a bad reputation, but they fought hard against this, and worked tirelessly to make the school a safe and supportive environment for everyone there. They too reminded me of many of my friends who I had left behind in Flint.

It was also during these few years in London that I first begin to seriously explore playwriting. I signed up for a young writers course at the Royal Court Theatre, a London theater that had been championing new work and new voices since it was founded in the 50s, and during a ten-week writing course I begin writing what I consider to be my first “real” play. It was called February. It was set in Flint, and inspired in part by the fatal shooting of 6-year old Kayla Rolland in Beecher (just north of Flint) in 2000, and my own experiences working briefly in various Flint Schools.

I still remember the day I got the phone call from the theater telling me that the play had been shortlisted for their young writers festival. I answered the call on my cellphone on a busy street near Goldsmiths, and ducked into a phone booth so I could hear better. They told me they were interested in developing my play, I said thank you, hung up, and then burst into tears. These were of course, happy tears. A theater I admired greatly was interested in my play about Flint, Michigan! I immediately began rewriting, trying desperately to make it what I thought the Royal Court wanted. But the results were dismal. Like many works of art made about Flint, the play portrayed the city as a bleak, hopeless place from which people are desperate to escape. Many people I met in London already had this image of Flint in their minds, thanks mostly to Michael Moore’s Roger & Me. The story I was trying to tell didn’t challenge this perception, it simply reinforced it.

Eventually the theater passed on the play. They called with the bad news on what was meant to be my last official day of work at Deptford Park. I stepped out of a classroom to take the call, and then went and sobbed in the art supply closet.

Shortly after completing my masters program, I began running the young people’s theater project at the Blue Elephant Theatre in Camberwell, another South London community that just like Deptford, reminded me very much of Flint. I stayed for three years, and gradually took on more projects, including creating a theater program with residents of the Bethwin Estate, and running the Speak Out Forum Theatre Project, making work that explored many of the systemic issues facing young people in London.

For a while, it felt like I was making a new life for myself in London. I was creating theater that I felt made a difference, and I was beginning to wonder if I would stay there for good. However, Flint was very much always on my mind. Added to this was the fact that I still had a Green Card, granting me permission to live and work in the U.S. On a trip back to the States for my brother’s wedding, an immigration officer began to ask questions about where I was living. I was informed that if I wanted to keep the Green Card, I would need to return permanently to the U.S., or I’d be asked to surrender the it.

After months of agonizing over the decision, making multiple pros/cons lists, and seeking guidance from close friends over multiple evenings at the pub, I finally bit the bullet and decided to return to the States. While I was happy with the life I was making for myself in London, I realized at that point in my life I didn’t feel ready to commit to living in the U.K. forever. While I was living in London a former professor of mine from UM-Flint, Dr. Lauren Friesen, brought several groups of theater students to London for a month for a study abroad trip. I would meet with them, and talk about my work, and during one visit I mentioned the possibility that I might be back in the states in the future. Friesen said that if I ever ended up back in Flint he’d love to have me teach some classes at UM-Flint. I returned to Michigan in the spring of 2010, and began teaching my first classes in the summer semester.

I didn’t think I would be in Flint for very long. I thought I’d teach for a year or so and explore my options. When in London, I loved being in a large cosmopolitan city. I assumed I’d maybe make the move to New York or Chicago, but it’s now almost six years since I came back to Flint, and I’m still here. I still teach part-time at UM-Flint, and for the past three years I’ve also been working at the Flint Youth Theatre where I am now the playwright in residence. I don’t know if I’ll be here forever, but for the time being it does feel like this is where I need to be.

I don’t say this to suggest Flint needs people like me (a gay, white British guy who makes theater). The story of how I ended up here and why I stay still confuses plenty of people, but it makes a lot of sense to me. I know now I couldn’t have done the work I did in London communities like Deptford and Camberwell without the experiences I had whilst in Flint, and I know I couldn’t do what I do in Flint today without the lessons I learned in the six years I was away. Flint could quite easily do without me, but I don’t know how I would fare if Flint wasn’t still a huge part of my life.

The story of how I ended up here and why I stay still confuses plenty of people, but it makes a lot of sense to me.

I’m still writing plays, many of which are very much about Flint. I’ve written about the impact of arson on the city, the anti-democratic Emergency Manager legislation passed by Governor Rick Snyder and the response by activists in the city, and the rise in vacant city lots being transformed into beautiful community gardens. While I consider February the play about Flint I needed to write in order to learn what kind of play about Flint I didn’t want to write, I had to return to the city before I could finally write Bloom, the play that had been escaping me for so long.

I’m going to turn 34 later this year. Very soon I’ll have spent more of my life in the Flint area than I have in the U.K. Despite not having the honor of being born in this place, I do feel like the city is my adopted home. I’m very protective of this place; I’ll defend it whenever necessary, and I now see how instrumental this city has been in making me the person and artist I am today. However, I still feel slightly uncomfortable to claim that I’m from here, and I think this is because I feel like I haven’t done enough to earn that distinction.

I understand that the fact that I choose to remain in Flint sets me apart from the significant number of residents who would like to leave but, for many complex reasons, are unable to. I also understand why not everyone feels the same way about this place as I do. I’m fascinated by those with questionable ties to this place who still embrace the “Flint identity” because perhaps they think it makes them appear tough, or cool. However I think if you’re going to claim this identity, you need to earn it. You need to understand and be willing to grapple with the deep complexities of this community, and be willing to put in the effort to help make this place more just and equitable for everyone who lives here. Being able to claim Flint is a badge of honor, and one that I’m still in the process of earning.

Flint is more than good enough, and certainly fancy enough for a British guy like me. The question I still constantly ask myself, though, is this: am I good enough for Flint?

Excerpted from Happy Anyway: The Flint Anthology (Belt Publishing, 2016).

Andrew Morton is a playwright and theater-maker based in Detroit. His play Bloom won the 2013 Aurand Harris Memorial Playwriting Award and premiered at Flint Youth Theatre in 2014, and has since been produced in Ohio, North Carolina and Australia. He has worked in London with several educational theater companies and was the Education Officer at the Blue Elephant Theatre, where he ran the Young People’s Theatre and the Speak Out! Forum Theatre project. Morton currently teaches theater at the University of Michigan-Flint and works as a Teaching Artist and Facilitator with a variety of arts and social service organizations throughout Southeast Michigan.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the people of the Rust Belt, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.