By Amy Kenyon

This is a memory of two letters written during the last years before home computers and social media. I wrote the first letter by hand, but typed the second one on a Smith-Corona. Both letters required visits to the town library to ask for help in locating postal addresses. Both called for the purchase of a stamp and envelope, or, failing that, the theft of those items from my father’s desk drawer. And my letters involved a walk from our house in suburban Detroit to the nearest mailbox—a mission, in my young mind.

The first letter was posted during a winter storm in December 1963. I was nine years old. Wearing my duffle coat, red mittens and rubber boots, I placed the letter deep in my pocket to keep it dry. I made my way in blizzard conditions. Drifting snow, a near whiteout. Left at the end of our street and then over two blocks to a particular mailbox, the one next to the big highway that led to Detroit. Leaving small footprints in the snow to be dusted over by more snow, I passed dozens of box houses strung with Christmas lights, many switched on to make the blizzard festive. Newly built, each house had cost less than $12,000, and favorable 30-year mortgage deals had been given to young family men who came back from the War. As I walked against the wind and flurries, I brimmed with love for the streets of “ticky-tacky.”* These were the last years before my distrust of the place began to set in. Each driveway boasted an oversized Ford or Chevy, now disappearing beneath thickening white. Engines silent on cars owned by the people who made and sold them. Detroit, you were quiet that day. Did I dream you? Your glorious skyline, your elegant department stores and grand movie palaces, were lost in the blizzard.

My lines to Jackie are gone, but I recall the physicality of writing, the deepening wax rainbow that formed along the side of my hand, a left-hander’s stain.

We, less than 20 miles away in suburbia, were muffled by the storm. Offices closed and school cancelled. A “snow day” in December 1963, like Christmas come early. I was hoping for my first pair of figure skates. I was possessed, too, by a child’s sense of self-importance. I should have figure skates! I should glide on smooth ice, the future belonged to me. My body, my opinions, my emotions, would soon find a place out there. On the wide thoroughfares. Atop the tall buildings downtown. Above the waters of the Great Lakes. Therefore, it mattered that I write to Jackie Kennedy to tell her how sorry I was about Jack.

I had made her a condolence card, using blue paper (for sadness) and crayons, selecting a different warm shade (from a prized Crayola 64-color pack) for each letter of my message (to cheer her up, little girl to big girl). Curiously, I no longer recall the words I chose. Nor do I possess a copy. We used to send letters without copies or trace, and this calibrated the process differently. My lines to Jackie are gone, but I recall the physicality of writing, the deepening wax rainbow that formed along the side of my hand, a left-hander’s stain. Practicing cursive letters in school, the southpaws were a small group. We dragged our hands across our writing, haunting our own words, leaving smudges on the page as we gathered layers of pencil, ink or crayon to our skin. Our stain was a residue of our efforts, a mark of identity. This began to disappear when we laid down our pens in favour of keyboards. My hand is clean these days. I look elsewhere to think about left-handedness. Baseball principally, pitcher-batter matchups.

Response note sent by Jackie Kennedy in December 1963. Image courtesy the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

Jackie’s reply, preserved in boxes of family memorabilia for the remainder of my childhood and after I left home for college, finally disappeared when my father retired and my parents moved away from Michigan. Sometimes, I still mind that it went missing, but I can picture it clearly enough—or of course, nowadays, just google a photograph of one of the mass-produced cards. After all, I was only one of some 800,000 people, including many children, who wrote to Jackie after the assassination.

***

It has been said that November 22, 1963 became a “flashbulb memory”: the phenomenon in which an intersection of personal memory with the occurrence and reporting of a public (often traumatic) event causes that memory to be heightened. It is why, many years later, people report vivid descriptions of the circumstances in which they learned of the event: where they were, what they were doing and with whom, what song was playing on the radio. Although the phenomenon had been observed at least as early as the decades following the Lincoln assassination, it was not until 1977 that psychologists Roger Brown and James Kulik proposed the term flashbulb memory, a photographic metaphor, to emphasize the enduring perceptual sharpness that attends such memories.

When the motorcade rolled through downtown Dallas that Friday, I was in elementary school. The principal interrupted our class to announce that the President had been shot. We gasped in unison in our rows of little desks, the teacher trembled, and our grandfatherly principal patted her shoulder. We were sent home early. I raced downstairs to the basement where the television was alight, and remained there. My mother made a few feeble attempts to unglue me from the screen, after which she gave up and joined me. By the time my father arrived, Kennedy had been pronounced dead. I remember how relieved I felt that it happened on a Friday, so my father would come home in his relaxed weekend mode, mix a martini for himself and sit with me. We would be together, safely underground, my parents, older sister and brother. We would hunker down with Walter Cronkite and believe ourselves part of a nation of equals, uniformity and consensus. Citizens strung together by our glimmering screens.

President John F. and Jackie Kennedy in the presidential motorcade, November 22, 1963. Public domain photo by Victor Hugo King.

This was the era of three main networks, all of which halted regular programing and seemingly time itself, to provide coverage of the assassination and Kennedy’s funeral. Television was a young medium in 1963, and during that November weekend, we devoured it like pizza. We stuffed ourselves on its promise, its excess.** I recall the shocking immediacy of Jackie in her pillbox hat and dark-stained suit. Bloodied roses left on the back seat of the limousine—blood made surreal in black and white, and the more disturbing for it. Interviews with traumatized bystanders along the parade route. Finally, on live television, the Sunday shooting of Oswald by Jack Ruby. We are now a nation inured to gun violence. Back then, we felt a collective horror that such a thing could occur so casually, in the presence of dozens of police and FBI officers, before the cameras, before our eyes. Television had knitted us together that weekend, from sea to shining sea, to show us this?

Yes, these were flashbulb moments that would be held in memory. But I know that sometime before they occurred, I was already unfurling a malaise in myself. And if my malaise had a geography, a place in which to reveal itself slowly, our basement was that place. In the late 1950s and early 60s, suburbanites began to “finish” their basements. My parents panelled the walls of ours, put down red linoleum tiles over the concrete floor, and hung ceiling-to-floor curtains of bamboo, dividing the large room into two spaces and functions. On one side of the bamboo—the side I thought of, in those Cold War years, as utilitarian East Berlin—were the furnace, washer and dryer, and a huge freezer packed with frozen food. If my brother and I were sent to fetch something from the freezer, we had to steel our nerves before crossing to that side of the bamboo curtain. When we raised the freezer’s heavy lid, we shivered as frosty light escaped from a bed of ice-encrusted red meat. We soon raced back to West Berlin where the joys of rampant post-war capitalism prevailed. Television and record player, glossy magazines, a stack of Elvis singles belonging to my older sister, my brother’s model car collection. Sofa and chairs, cosy rugs and cushions. For Dad’s after work cocktail, coasters on the coffee table, each one depicting an early Ford from Model T onward.

Sitting through the secret daydreaming hours of childhood, cross-legged on the basement sofa, I beheld this succession of public events, each one adding to the wear and tear on my psyche.

It wasn’t long until events conspired to make me as uneasy in our basement’s West Berlin as on the other side. It was there, in August 1962, that I watched the newscast of Marilyn Monroe’s overdose, tried to imagine the star’s puffy flesh in death, overheard the adults commenting that it came as no surprise, as though there were something about Marilyn that had predetermined such an end. It was there, too, that my brother and I followed the Cuban Missile Crisis, certain that Detroit was a target. And after the events of November 1963, it was as though language itself became unsafe. Particular terms, once unremarkable, now entered the lexicon never to ring innocently again: motorcade, grassy knoll, book depository, Elm Street. I needed a new language, but my nine-year-old self had no clue where to find it.

Sitting through the secret daydreaming hours of childhood, cross-legged on the basement sofa, I beheld this succession of public events, each one adding to the wear and tear on my psyche. Gradually—across three or four years, across hot summers playing outside until the streetlights came on, followed by fall and throwing ourselves into piles of leaves, then winters skating on ice made by flooding the backyard to freeze it overnight—very gradually then, the restive beauty of changing seasons took hold of me and would not let go. I would grow older. The child who posted Jackie’s letter, shining her confidence into the snowstorm, would give into uncertainty. I began to allow for the wider possibilities of deception and delusion, to have doubts about a number of things, not just the presumed happiness of a Hollywood blonde, or the lone assassin theory, but matters closer to home, my parents and their histories, and the things they purported to believe.

Take an example: my parents kept changing the story of when and where they married, and we three children began to suspect that a family secret was in play. Or consider my father and Ford Motor Company. A veteran with a college degree and first little house financed through the GI Bill, he was an organization man. He worked hard for Ford all his life. And we were true Ford brats. One Christmas morning, to slow our charge to the pile of gifts beneath the tree, Dad told us that Santa’s sleigh had “stalled” down the street and so he hadn’t come yet. Forget the reindeer; in Michigan, Santa ran on gasoline. Yet one Thanksgiving, flushed with Bordeaux wine, regret in his voice, my corporate father made the aberrant remark that although he sold them for a living, he had never cared much for cars.

Seasons passed. Santa unreliable, family history unreliable, Henry Ford in less than heroic light, Marilyn dead. The Warren Commission came and went, never stilling the doubters who found conspiracy theory so pleasurable. We purchased a new television and soon it began broadcasting images from Vietnam, in color that bled into the room and disturbed our night-time thoughts. God? Where was he during these changes? I went willingly to church, looking for him as I sat in the pews, but he had never shown himself to me and I was losing interest in that particular project. I began to suspect that information about God, and a host of other topics, was being withheld so that I might acquiesce in ideas I had not freely chosen. I did not know what this information might be, but it seemed to hover close-by, in the spaces of my comfort. At home, on the streets where we played, in our suburban backyards and school playgrounds. What kind of place was it where the summer sun always shone on tidy green lawns and pink kids in paddling pools? What was I not being told?

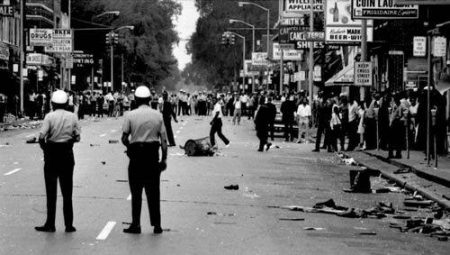

Then, in 1967, during hot July, Detroit erupted in the most serious urban American uprising to date. Forty-three people died (33 black, 10 white), 2,000 were injured, and 7,000 were arrested. In our suburb, we stood on the front porch watching the sky turn a sickly yellow as the unseen city burned beneath. We heard and repeated the wild rumors of black conspiracies against the subdivisions.

12th Street in Detroit, July 23, 1967. Public domain.

At the time, I experienced a flutter of doubt; I tried to guess where the rumors had originated and how they had reached as far as our neighborhoods. I also reflected that not one of us had ever met a black person, and wondered what they might be saying about us. Children deal in rumor all the time and are surprisingly adept at knowing that the transmission of rumor is as important as its content. It would be many years before I returned to these specific stories and the context in which they occurred, before I grasped that the real conspiracy was right beneath my feet, in the history and geography of our little houses and postwar suburbs, and in our self-deception about segregated spaces and the city. Standing on the porch that summer, I lacked knowledge. I lacked words. But I was learning to live with my malaise, even to see it as productive.

***

Two years and several Ford Motor Company promotions later, my father moved us to a wealthier subdivision farther from Detroit, out where the lanes were winding and the building lots larger. Gone were the box houses. We now lived in a faux Cape Cod house with modern fittings and—perhaps the biggest change—we no longer needed a finished basement because the new house had a “family room.” By the time of our first Christmas there, in 1969, the year I turned fifteen, the baby boom was running its course. We kids had put away our toys and taken to hiding in our rooms, listening to Abbey Road on the record player and wondering if Paul McCartney was dead. That year, the holiday post brought a Christmas card from Henry Ford II and his wife, Cristina. It had a satin cover with a Model T embroidered into the satin. Our father seemed unmoved, remarking that he must be one of thousands to make the Fords’ Christmas card list. He had never met the man, he said. It was a question of salary grade.

I think now that his reaction to the card, together with his rueful comment at Thanksgiving some years earlier—these were fleeting glimpses of a secret sadness. Our father made choices during those years. He believed in his choices, in the rightness of them. Were he to live again, I am quite sure he would make the same choices. But that does not mean he carried no regrets or felt no grief about the direction his life had taken. Perhaps he had given up something so that we might live many rings out from Detroit, in a new house that felt staged to us, and for which we were not grateful.

I remember my own lack of gratitude. By now, I was honing the sullen misery of a teenager into a critique of our displacement—from one suburb to another. Even this half-century later, I can recall the feel of the wound. It was political and emotional. Not only did I see the move to the wealthier suburb as some sort of class betrayal, but I missed my friends terribly. This, in turn, had the odd effect of giving my prior suburban malaise a new and contradictory sensation. I missed the very place that had seeded my earliest suspicions of the world. I began to long for the old suburb with the ferocity of Dorothy’s desire for drab Kansas after her landing in Oz. At fifteen, despite all the comforts of our new dream home, I succumbed to a serious bout of home-sickness.

In time, I would come to see that these contradictions had a great deal to do with Detroit, the city always beyond my grasp.

It would be many years before I learned that Ray Bradbury had been yanked from his hometown at roughly the same age. Bradbury was thirteen when his family moved from Waukegan, Illinois to Los Angeles. “I left at just the right moment,” he later remarked, “so that nostalgia set in almost immediately.”*** Knowing this now, it seems fortuitous that I first read Bradbury soon after moving, and that the book I chose was Dandelion Wine, his great semi-autobiographical novel of Midwestern boyhood. With its lyrical prose and love of place, its hometown that was beautifully familiar and disturbing by turns, its dark mélange of childhood adventure and fears, and finally its explorations of aging and death, Dandelion Wine reached a long, bony hand into my heart and twisted it until I wept for my own lost places and times. I loved the book obsessively, vehemently, reading it over and over during the hours of loneliness in the new suburb. Then, slowly, over many months, I relented. I began to adjust to the outer circumstances of the move, a new school and the need to seek new friends there. But I am not sure I would have managed it without Dandelion Wine.

I kept the book at my bedside until I left home for college. Before leaving, I wrote and posted the second letter. It was October 1971. The leaves had started to turn. Reds and golds, fastened to trees or loosed by the wind, somersaulting downward and making a skittish carpet beneath my feet. I favored the month that brought my birthday, October baseball, Halloween, the anticipation of winter—autumn would pass too soon. Seventeen years old and already feeling the loss and longing that attend the passing of seasons.

Again, my words are lost. They went to Ray. But I know that I thanked him for helping me through a difficult time, for showing me a language for these changes, as well as for that old malaise that had started long before, in the other suburb. I didn’t quite know it yet, and so could not have said it to Ray, but the old suburb had a hold on me that I would spend the rest of my life trying to understand. I was only beginning to realize how conflicted my feelings about it were, veering wildly as they did from deep attachment to grinding distrust. In time, I would come to see that these contradictions had a great deal to do with Detroit, the city always beyond my grasp. I had never lived there. My grandfather was the last true Detroiter in the family. But I understood that the suburban spaces of my childhood were implicated in the fortunes of the city and its inhabitants. This fact, yet to be examined, was the source of my malaise. It was there that day in the snowstorm when I posted the first letter. And it was there after we moved, when it struck me as an important loss that from the new suburb we would never have seen the yellow sky over Detroit when it burned in 1967. We had gone too far.

***

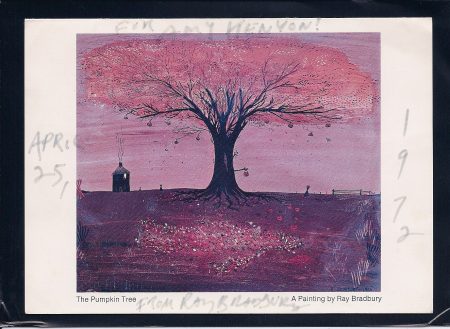

Ray Bradbury’s reply to the author. Image courtesy Amy Kenyon.

Now, I am growing old and live in another city, a continent away. I’ll never know Detroit, but I still dream about it. Ray Bradbury’s reply is the only material evidence that remains of my two letters. I keep it on my desk, a card with a front cover featuring one of his paintings titled The Pumpkin Tree. As for his kind and encouraging message inside the card, that will remain for me alone. Those were the days of private letter writing.

___

* This descriptor comes from a 1962 song about suburbia, titled Little Boxes and written by Malvina Reynolds.

** In retrospect, network coverage of the Kennedy assassination has been described as the moment “America became a TV nation.” See Patty Rhule, cited in Jon Herskovitz, “How the JFK assassination transformed media coverage,” Reuters, Nov. 21, 2013. For a more detailed look at this topic, see Barbie Zelizer, Covering the Body: The Kennedy Assassination, the Media, and the Shaping of Collective Memory, University of Chicago Press, 1992.

*** Ray Bradbury, quoted in Henry Stewart, “Childhood’s End: Death and Growing Up in the Books of Ray Bradbury,” Electric Literature, Feb. 9, 2015.

Amy Kenyon is a historian and writer-photographer. She is the author of Dreaming Suburbia, a study of Detroit and postwar sub-urbanization (Wayne State University Press) and a historical novel, Ford Road (University of Michigan Press). As a writer of short fiction and nonfiction, she has published with Bright Lights Film Journal, Salon, Belt Magazine, Great Lakes Review, Streetlight Magazine, Eclectica Magazine, Cobalt Review, and the Detroit News. She is also a regular blogger for Huffington Post UK. Born and raised in Michigan, Amy now lives in London. See amykenyon.net.

What clarity of memory and illumination of them with innocent prose. I’m in awe.

I knew you in the “outer ring” and now realise that I didn’t know you at all, but we shared the TV room reality of suburbia.