How Unigov, a 1970s-era legislative project, helped create modern-day Indy and its suburbs.

By Nicole Poletika

In any conversation about Unigov, a good place to start is with the name—that technical, distinctly mid-century-sounding title for the 1970 consolidation of city and county governments in Indianapolis and Marion County, Indiana. As you might have guessed, it’s a combination of “unified” and “government.” Administrative mergers, if you ask my opinion, are far from sexy. But in the case of Unigov, what initially seems like a droll story about agency streamlining is in fact another chapter in America’s history of expansion—social equity be damned.

The story of Unigov begins in the middle 1940s, at the conclusion of World War II. Returning Hoosier servicemen and women flocked from center-city Indianapolis to rapidly-growing suburban housing developments. These new suburbanites, who were largely white and middle class, took their tax dollars with them, establishing, over the ensuing decades, a powerful base outside of the city and its urban core. Those who came into town did so primarily for governmental and business purposes. The city boasted one hotel, the canal teemed with tires, and fumes from the meatpacking plant permeated the city. Not much existed in the way of business or recreation. Mayor William Herbert Hudnut III, who served from 1976 to 1992, later recalled that, in pre-1970 Indianapolis, “It was said you could shoot a cannon down the street after five o’clock and not hit anybody.”

Indy’s champions feared the city’s collapse, especially given the decline of manufacturing, and began to think audaciously about its future. One idea, popular among said champions, was a unified city-county government. In 1967, Republicans swept the municipal elections. The newly-elected mayor, resourceful Republican Richard “Dick” Lugar, quietly assembled a group of local lawyers and political and business leaders—twenty-nine in all—to a Mayor’s Task Force. He wanted to draft legislation that would consolidate the governments of Marion County and Indianapolis, in hopes of revitalizing the city’s atrophied core, and needed to give the impression that the private sector supported the reform efforts of what became known as the “pro-Consolidation machine.”

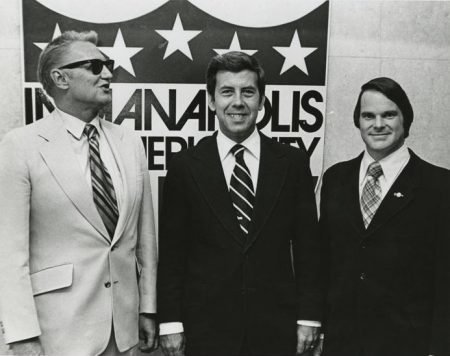

Thomas Hasbrook (L) and Richard G. Lugar (C), major players in the development of Unigov, with Mike Carroll (R), deputy mayor of Indianapolis. (Courtesy University of Indianapolis Archives and Special Collections.)

Over the next couple of years, the task force put together a plan for Unigov in secret. It went like this: Unigov would merge thirty-one departments and eleven agencies into six departments within the executive branch. These included administration, public works, public safety, metropolitan development, parks and recreation, and transportation departments. This consolidation was intended to streamline government services, but, in many respects, it complicated them. The plan would also create a City-County Council, whose members are elected every four years. The council would oversee city funds, levying taxes, and developing budgets.

In the short term, the merger, billed as making government more efficient and services less expensive, created a powerful City-County Council and ultimately strengthened the influence of the mayor and Republican Party. But that was only the beginning of its influence. The resultant development in Indianapolis and Marion County speaks to the American impetus, and even entitlement, to acquire territory. As with the gains produced by Westward expansion, Indy’s enviable transformation came at a cost to disadvantaged groups and widened the gap between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” But this expansion also benefited a majority, played a large part in the creation of central Indiana’s affluent suburbs, and rid the city of its nickname “Indiana-No-Place.”

Once Lugar publicized the plan, debate ensued. Business leaders, the League of Women Voters, and the majority of the local press supported Unigov. Most of the resistance—albeit unmounted—came from labor leaders, the Democratic Party, and the African American community, which feared the dilution of its political influence with the addition of hundreds of thousands of white, middle class, conservative residents to the city’s population. An article in the Indianapolis Recorder, an African American newspaper, noted that Black residents made up thirty percent of the county’s population, “and the general fear among Negroes is that the [City-County] council would be gerrymandered in such a way that Negro representation on the council would be kept at a minimum.”

Indianapolis’s Black community, particularly along Indiana Avenue, had been displaced in the 1960s with the establishment of IUPUI and the interstate. The health and influence of the cleaved Black community would again be diminished with the passage of Unigov. Many people feared—and history bore this out—that the new voters and the predominantly white council would act in their own best interests, prioritizing skyscrapers over, for example, struggling public schools. Some also worried that Unigov’s planners sought to eliminate the possibility of a Black mayor.

Unigov, which went into effect in 1970, added about 250,000 new residents to the City of Indianapolis overnight.

In 1968, African American parents successfully lobbied the U.S. Justice Department to file suit against the Indianapolis Public School system, charging unconstitutional segregation. With the lawsuit pending, Unigov planners excluded schools from consolidation. (Safety departments were also excluded.) A federal judge later ruled that the “state intentionally discriminated against the black pupils in Indianapolis Public Schools by expanding city government to the county line and leaving IPS and ten predominantly white suburban school districts in tact.” By leaving the school system out of Unigov legislation, planners had avoided a major roadblock to the consolidation’s passing, but they also further cemented segregation and disparities in education, which endure today.

Indiana’s General Assembly passed Unigov legislation in 1969, without a public referendum. Some people were angry. Unigov’s proponents knew that, should the public be allowed to vote on consolidation, it would likely fail. The decision upset precedent, as residents had voted on the 1958 Nashville-Davidson County consolidation, in Tennessee, and 1967 Jacksonville-Duval County consolidation, in Florida. Indianapolis’s generally well-meaning political and business leaders would enlarge Indianapolis, even if it meant not seeking meaningful public input, disallowing a public vote, and essentially excluding disadvantaged groups from the benefits of Unigov.

Unigov, which went into effect in 1970, added about 250,000 new residents to the City of Indianapolis overnight. In doing so, it took political representation from those who perhaps needed it most and increased taxes for those who often earned the least—those who called the “old city” limits home. The project was intended as a first step toward a vision of a thriving, modern city, and in some ways it worked: the city’s new suburban tax base helped transform the city known solely for the Indianapolis 500 into a sporting (and potentially convention) capital of the world. Prominent African American columnist and radio host Amos Brown III noted that the merger would transition Indianapolis from a “backwater” to a “top tier city.”

With Unigov’s passing, some residents were eager to rebrand the city and change its national reputation. “Old fashioned city of another era; nineteenth century Crossroads of America; growing older every minute; the retirement home for Father Time. In name only. In reality, no, no, no, a thousand times no!,” proclaimed R.T. Hamilton Brown, a resident, in a letter to the editor in the Indianapolis Star. Brown went so far as to propose renaming Indianapolis “Unigov City.” With an enlarged population that generated more tax revenue and qualified Indianapolis for federal loans, the city quickly got to building. By the end of the decade, it had Market Square Arena and a renovated City Market. By the 1980s, it had the Hoosier Dome, Indianapolis Zoo, Union Station, and the Pan America Games, sort of an olympics for the hemisphere.

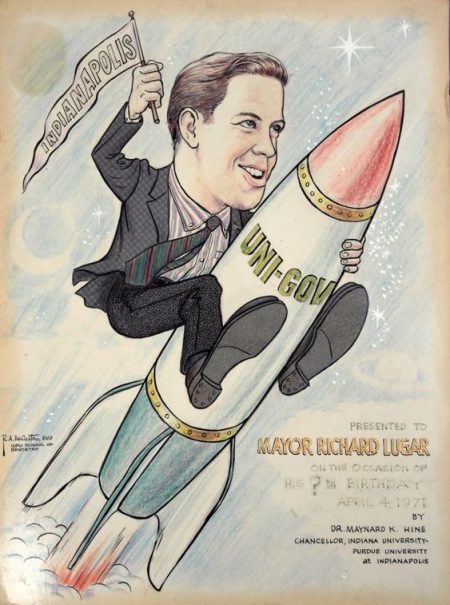

Drawing of Richard Lugar riding a Unigov rocket. Delivered on occasion of Lugar’s birthday, April 4, 1971, and presented by Dr. Maynard K. Hine, Chancellor of IUPUI. (Courtesy University of Indianapolis Archives and Special Collections.)

Although it had a long way to go, Indy was on track to become one of the world’s sports capitals. Sharon Cohen wrote in Ohio’s Mansfield News-Journal, in 1987, that “Some cities are blessed with seashore splendor or majestic mountains. Others have glitz and glamour. This one has something else. Call it Hoosier chutzpah.” Aaron Renn, urban analyst and Senior Fellow at the Manhattan Institute, has argued that “Indy really pioneered the notion that you could use sports as an economic development tool.” The Indianapolis Star remarked, “Indianapolis 1984 bears little resemblance to Indianapolis 1969.”

All this boosterism was reminiscent of one of Indy’s most famous titles: “no mean city.” As the story goes, the phrase originated with native son President Benjamin Harrison, in 1897, and was reiterated by a mayor in 1909. The current city website has this explanation: “Indy’s a friendly, welcoming place. But it’s more than that. The city is also bold, significant—better than average.” Like all marketing taglines, this one carried a nugget of truth, but it also glosses over the real challenges facing marginalized communities in the city.

For all its accolades, Unigov intensified inequity between Center Township—the middle of the city—and Marion County’s formerly-suburban communities. A 1990 editorial in the Indianapolis Star credited Unigov with the city’s increase in violent crime and drug use: “When UniGov gave affluent suburbanities unbalanced power over the city government the poor found they had less influence in city decisions, when large banks and insurance companies obtained millions of dollars in city assistance for skyscrapers to be filled with ‘professional’ workers and their staffs, the poor found their cut of the economy had eroded to the point where service jobs with limited hours and menial wages were the only opportunities left.” City-County Councilman Glenn Howard put it more succinctly, claiming that Unigov “created a council insensitive to the needs of the poor,” and that “You don’t cut off poor folks and bring in suburbanities.”

Opponents of Unigov invoked a familiar cry: taxation without representation. In a 1994 editorial published in the Indianapolis News, resident Pete Peterson wrote that “The old Indy never got to vote on the idea and now effectively is disenfranchised by the former suburbs. Someday, perhaps even those outside the old city will realize that Unigov is a fraud and will allow true Indy residents to pick their own public officials.” Jack Price agreed and wrote to the Indianapolis Star that while residents of the “old city” pumped funds into formerly suburban areas and downtown properties, which benefited from tax abatements, they experienced a decrease in services like snow removal. Urban experts Neal Peirce and Curtis Johnson argued in 1996 that Center Township residents and businesses “are so overtaxed that they’re being denied the equal protection of the laws guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution.”

Pretty soon, certain people started leaving Unigov Indianapolis. They were unhappy about paying higher taxes, receiving worse services, and attending lower-ranked public schools than ring cities like Carmel, Fishers, and Greenwood. A second wave of (generally white) flight led to the monumental rise of suburbs around Marion County. Between 1970 and 1990, the population of Hamilton County, to the north of Marion County, doubled. Planners had to scramble to keep up with housing and commercial demands. My family moved from California to Carmel in 1992, and the cornfields which then gridlocked our neighborhood are now populated with McMansions. The quaint O’Malia’s Supermarket down the street quietly closed, and now Carmelites can shop at a store dedicated exclusively to gourmet olive oils in the city’s ambitious, if somewhat inauthentic, Arts & Design District.

Unigov changed the city’s landscape in a way that many of us benefit from today, but at the expense of groups with fewer resources and less political power.

Suburbanites commuted to Indianapolis for work and recreation, and retreated to communities recognized nationally for their safety and education. Peirce and Johnson, the urban scholars, wrote that “People seem to love the new downtown Indianapolis but shun the idea of relieving Center Township of its grossly unfair tax load.” SAVI found that when white residents fled to the suburbs, between 1970 and 1980, they depleted the city of many college-educated and high-income households. This left behind Black households unable to move to these same suburban communities due to real estate and lending discrimination.

Indianapolis’s urban sprawl isn’t always evident, and it’s easy to be deceived into thinking that the city is keeping up with its suburban neighbors—with First Fridays programming and trendy Lime scooters. But Renn has argued that an active civic sector in the city, anchored by companies like Eli Lilly, has “essentially financed and enabled the retreat of government from its functions and responsibilities” and “masked the collapse of government at the city level.” Between 2000 and 2010, downtown lost 13,898 private sector jobs and the rest of Marion County lost 45,697, while the suburbs gained 58,082.

Some people believe the tide is beginning to turn for “Unigov City.” Nancy Comiskey wrote recently, in Indianapolis Monthly, that thriving suburbs can serve as a “gateway drug” to the city, especially for empty-nesters and millenials. And, as Renn claims, the sustainability of the idyllic suburb is questionable. “As early inner ring suburbs across America increasingly face decay, poverty, and crime, it is clear that the allure wears off,” he explained. If cities like Carmel, Fishers, and Zionsville suffer the same fate as the formerly suburban areas of Marion County, will Hoosiers flock back to Indy’s historic neighborhoods?

Work occurs on a sewer line around Monument Circle in downtown Indianapolis, 1978.

The contemporary political landscape in Indianapolis is in a position to reverse some of the social and economic inequities imposed by Unigov. The current City-County Council’s Democratic majority could also alter Indy’s educational, social, and civic landscape. With the 2015 election of Mayor Joe Hogsett and other city officials, Democrats are in power across the board for the first time since Unigov was signed into law. The city-county council president, Vop Osili, is Black. This new majority will certainly have different priorities than the Republican administrations that transformed Indiana-no-place into Indiana-some-place. Perhaps they will stop kicking the can down the road and instead refashion it.

As conservative, middle-class people have moved to the suburbs, Modern Marion County voters are more likely than before to support social and welfare programs and school consolidation, issues that had been overlooked in the past in favor of courting businesses. And as African American households spread outside of Center Township and into Marion County’s former suburbs, Black political power is increasing. African American at-large Council member Leroy Robinson implored “the locals, the citizens, the ordinary people, and the underrepresented to rise up, stand up, and fight for the right to repair, improve, uplift, and control their own destiny, their own community and the conditions of their future generations.”

Meanwhile, a landmark project promises to quite literally drive Hoosiers back to the capitol city: the Red Line bus system. With Hoosier rapid transit decades in the making, Red Line buses will run from the Broad Ripple neighborhood on the north to the University of Indianapolis on the south. The move literally builds on the city’s transformative streetcar lines of the 1890s. By nature, the Red Line restores equity amongst Indianapolis residents lost since 1970. It has the potential to revolutionize recreational and job opportunities for Indy’s carless residents. Reportedly, future phases will extend the line from Westfield to Greenwood, furthering these opportunities. The Red Line could begin to weld the urban and suburban joints forged, in part, by Unigov.

Unigov changed the city’s landscape in a way that many of us benefit from today, but at the expense of groups with fewer resources and less political power. Its architects were acting in good faith on the information available to them at the time, but with significant historical blind spots. Indianapolis is at a crossroads as it approaches its 2020 bicentennial. But perhaps the city can learn from its past when it comes to improving the city in a sustainable way that benefits all. No mean city, indeed. ■

This story was produced in partnership with Indiana Humanities’ INseparable project. Read more stories in the series here.

This story was produced in partnership with Indiana Humanities’ INseparable project. Read more stories in the series here.

Nicole Poletika is an Indianapolis-based historian who focuses on issues of social justice.

Cover image of downtown Indianapolis construction in 1975. (Courtesy University of Indianapolis Archives and Special Collections.) The image has been lightened slightly for visibility.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.