Last week on Belt, we featured a Q&A with MIT anthropologist, author, and filmmaker Christine Walley. Her work on the steel-mill neighborhoods of Southeast Chicago (where she was born and raised) is at the center of her 2013 book Exit Zero: Family and Class in Postindustrial Chicago. Walley, working with her filmmaker husband Chris Boebel, is currently raising funds on Kickstarter to finish a documentary film of the same name. We’re excited to share a selection from Walley’s deeply compelling writings on family history and the community structure of Southeast Chicago. “A World of Iron and Steel: A Family Album” is excerpted from “Deindustrializing Chicago: A Daughter’s Story,” originally appearing in The Insecure American: How We Got Here and What We Should Do about It, edited by Hugh Gusterson and Catherine Besteman, published in 2009 by the University of California Press.

By Christine Walley

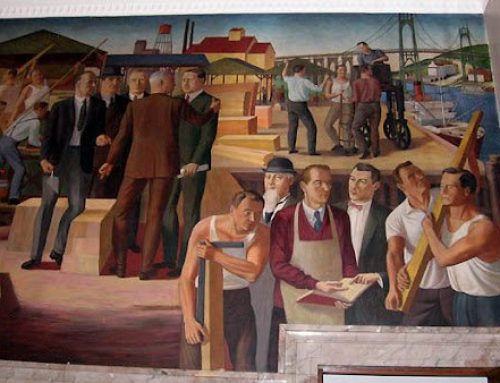

Defined by the steel mills that in the 1870s began drawing generations of immigrants to live near their gates, Southeast Chicago has what might euphemistically be described as a “colorful” history. Al Capone once maintained houses and speakeasies in the area because of of its convenient proximity to the Indiana state line. My dad would drive me around the neighborhood when I was a child and point out the brick bungalows rumored to have been Capone’s and to still have bulletproof windows. Laughingly, he told stories of how one of my great-uncles quit his job as a night watchman after Capone’s men showed up one evening and told him not to report to work the next day. One of the defining events in U.S. labor history, the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937, happened on a plot of land across the street from the local high school that my sisters and I attended. On that Memorial Day, locked-out steelworkers and sympathizers, including my grandfather, massed in protest near Republic Steel, where ten were killed and nearly a hundred wounded by police under the influence of mill management. A federal investigation and subsequent legislation were milestones in allowing U.S. workers the right to unionize. In 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. marched through the streets of Southeast Chicago protesting the deep-seated racial hatred and housing segregation in the area, to the consternation of many of the white working class, including many of my own family members.

[blocktext align=”right”]At times, the interconnectedness of the neighborhood’s kinship ties reached near comic proportions. For example, my mother’s mother, a widow, eventually married my father’s father, a widower, a year before my own parents were married.[/blocktext]What was most striking about growing up in Southeast Chicago, aside from the contentious relationships found among its patchwork of ethnic groups including Scandinavians, Germans, Poles, Slavs, Italians, Greeks, Mexicans, and, later, African Americans, was the neighborhood’s dense networks of kinship ties. Many families, like my own, had lived in the mill neighborhoods for generations. When I was growing up, my grandparents lived across the alley from my parents’ house, and nearly all my cousins, aunts, and uncles were within walking distance. My sisters and I attended the same grammar school as our parents as well as several of our grandparents and even great-grandparents. At times, the interconnectedness reached near comic proportions. For example, my mother’s mother, a widow, eventually married my father’s father, a widower, a year before my own parents were married. Despite perplexed looks when I explained that my mother and father had become stepbrother and stepsister as adults, the situation seemed and oddly appropriate expression of the dense social bonds that knit together the mill neighborhoods. At other times, the interconnectedness took on darker overtones. I remember my parents reminiscing about trying to decide as newlyweds whether it was appropriate to attend the funeral of my father’s aunt after she was killed by a distant relative on my mother’s side, a man who had become mentally unstable after serving in the Korean War and had exploded a bomb in a local department store.

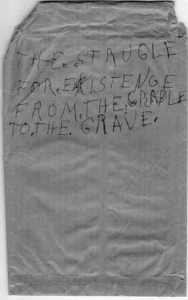

The cover of Christine Walley’s great-grandfather’s unpublished memoir, “The Strugle for Existence from the Cradle to the Grave.”

While families were at the root of social life, they also mirrored the divisions found among the white working class more broadly. In many ways, my mother’s family approximated the classic immigrant narrative of modest upward mobility, while my father’s family reflected the far-less-often-told reality of long-term white poverty. Although the immigrant narrative of my mother’s family story was valorized while my father’s family’s story was swept under the collective national rug, the accounts from relatives on both sides of the family built upon classic American myths of a modern industrial “melting pot” society and, at the same time, regularly contradicted such mythology. The story of my maternal great-grandfather is a prime example. My mother’s grandfather, Johan Martinsson, came to Chicago from Sweden in 1910, becoming John Mattson in the process. After his death, my grandmother found hidden in the attic a memoir stuffed in a paper sack that he had written in broken English at the age of seventy-five. The dramatic title The Strugle [sic] for Existence from the Cradle to the Grave was scrawled across the front. His wanting to tell his story so badly, yet feeling the need to hide it in the attic, has always fascinated me. To me, it suggests not only the ambivalence of wanting to convey—yet being afraid to convey—painful family events but also ambivalence about how to tell a life story that so bitterly contradicted mythic portrayals of immigrants grateful to be on American shores.

[blocktext align=”left”]His wanting to tell his story so badly, yet feeling the need to hide it in the attic, has always fascinated me.[/blocktext]John, or as I knew him, “Big Grandpa,” tells a story that both references and contests classic immigrant narratives that were intended to make sense of experiences like his. He recounts how, as a child, he grew up on a farm near Göteborg in Sweden and was apprenticed at the age of eight to a blacksmith. He later alternated odd days of school with hard labor for neighboring farmers. part of a large and impoverished family of thirteen, he left his community at the age of seventeen along with a group of other Swedes (including the father of his future wife) to find work in America. He worked for a while as a steelworker but was put off by the high death tolls of the mills. After received a lucky break, he managed to become a carpenter and later, as a union builder and contractor, would help construct buildings throughout South Chicago. Yet in contrast to the mythic accounts of immigration in the United States, he refers to his decision to leave for the United States as a “mistake” and one that “I should never had made if [I] had known what I know today.” He continues: “Sweden had peace for 150 years and do not [sic] meddle in another nation’s affairs. That’s more than I can say for my adopted country where I raised my family and worked hard since 1910. I was drafted in the First World War and had a son in the 2nd World War and now a grandson soon of age for Vietnam. When are [sic] this going to stop?” In addition to expressing his regret that he ever left Sweden, his story dwells in bitter detail upon harsh economic struggles as well as the festering sores of an unhappy marriage. He conveys the hand-to-mouth existence of his early years in the United States, the utter vulnerability and dependence of those like himself who were without resources, and the cruel insecurities of the life of a laborer.

In my childhood memories, I remember my great-grandfather as an enormous, taciturn man who always wore suspenders and occasionally still played the accordion. In old family movies from the 1940s, “Big Grandpa” can be seen riding a paddleboat-like contraption built by his younger brother Gust. Wearing a suit and hat, he stares at the camera from the industrial wetlands amid the steel mills. In contemplating this and other images, I try to locate the inner turmoil revealed in his writing beneath their impenetrable surfaces. Family lore has it that he tried to move back to Sweden in later years but found himself too heavy to ride a bicycle and came back to the United States. In such stories, the bicycle symbolizes the immigrant’s inability to go home, the dilemmas of a life transformed unalterably by the journey and caught betwixt and between.

[blocktext align=”right”]Women were in charge of the social world that gave life meaning in these mill neighborhoods, binding together kin networks, maintaining churches, schools, and ethnic organizations.[/blocktext]The women in my mother’s family left no written records, but it was they who, in my memory, were always at the center of things. In the early years of the steel mill neighborhoods, men vastly outnumbered women. Nevertheless, some women, like my great-aunt Jenny, ran the boardinghouses where steelworkers and other immigrants lived or, like another great-aunt, worked in the mill cafeterias. Others took in laundry, were waitresses, or cleaned houses for others, including the wealthy who lived in the mansions in South Shore. My grandmother did almost all of these at various points in her life and later supported my mother and uncle as a dentist office receptionist after her first husband died at an early age. In contrast to middle-class narratives that stereotypically portray working-class men as sexist and violent and women and children as their perpetual victims, in my experience it was women who were the powerful beings. They were in charge of the social world that gave life meaning in these mill neighborhoods, binding together kin networks, maintaining churches, schools, and ethnic organizations. While the men in Southeast Chicago might mark ethnic boundaries with belligerence and occasionally violence, the women could draw ethnic boundaries just as real through such acts as making Swedish holiday glögg and sausages, managing the Santa Lucia pageants in which we girls dressed up in white robes and silver tinsel, and organizing potlucks for organizations like the Bahus Klubben and the Viking Lodge. Like Steedman’s British working-class mother, who was a Tory and strove for the good things in life, many of the women on my mother’s side of the family gravitated toward cultural styles of respectability that they associated with refinement and “classiness.” It was this politics of desire for respectability, I believe, that made my utterly apolitical grandmother a Republican in the midst of this quintessential Chicago Democratic machine ward.

[blocktext align=”left”]Before coming to Chicago, my father’s family were tenant farmers and coal miners in southern Illinois. I never knew where they were from before that. When I asked my grandfather, he would answer angrily that were “American, goddamn it.”[/blocktext]While some of my mom’s childhood friends married “up” and eventually moved out of the mill neighborhoods to the suburbs, my father’s family represented the other side of the white working class. In contrast to the classic immigrant tales of upward striving, they were long-term white poor. Although my father’s mother was the child of Czech immigrants from Bohemia, her story is largely missing from the family album. Since it was the women who passed on family histories, her death when my father was barely more than a teenager meant that I grew up knowing almost nothing about here. In one of the few photos we have of her, she is standing next to my grandfather and surrounded by her sons, including my dad, who is positioned on the right. My father’s father was—I surmise—originally from Appalachia. Before coming to Chicago to work in the steel mills, his family were tenant farmers and coal miners in southern Illinois. I never knew where they were from before that. When I asked my grandfather (who was known to us as “Little Grandpa” to differentiate him from our maternal great-grandfather), he would answer angrily that were “American, goddamn it,” and tolerate no further questions. Later, I learned that he had asked his own father this same question upon arriving in Chicago and had received the same answer. In a place where nearly everyone was an immigrant from somewhere and in which ethnic affiliations, churches, and organizations were powerful institutions of social life and upward mobility, to be without an ethnic group was a form of deprivation. I only then realized that being “American, goddamn it,” was a statement not simply of racism but of the defensiveness of poor whites denigrated as “hillbillies” who were viewed as socially inferior to the incoming immigrant groups and who clung to their Americanness as one of their few badges of status.

[blocktext align=”right”]My grandfather could tell stories of men he had seen die. One friend of his had fallen when crossing a plank catwalk across an enormous vat of hot sand. The man succeeded in grasping the chain my grandfather threw down to him but suffocated before they could pull him out.[/blocktext]In many ways, my grandfather’s story is a classic tale of the rise of American labor and the transition from rural origins to the city. A family crisis occurred when his father, ill with “sugar diabetes,” was forced off the land in southern Illinois, where he had been a tenant farmer. My great-uncle Arley, then a teenager, rose to the occasion by leading the family to the north in search of opportunities for labor in heavy industry. Arley went first, hitching rides on freight trains and dodging the gun-toting railroad “dicks” (as detectives were then known) to reach Detroit. He then sent fare for my grandfather, who went to work as a waterboy in the car factories at age sixteen. Most of the family, including my great-grandparents, then relocated to Chicago a few years later. In Chicago, “Little Grandpa” eventually worked for more than forty-five years in an iron foundry, Valley Mould, that sat across the polluted waters of the Calumet River from Wisconsin Steel. Several of his brothers went to work in the other steel mills. Before the unions ameliorated labor conditions, “Little Grandpa” worked twelve-hour shifts, seven days a week, with one day off a month. When someone didn’t show up for work, he sometimes worked twenty-four hours straight. One day, a crane operator, who was working twenty-four hours, fell asleep at the controls as my grandfather and his fellow workers were extracting an enormous red-hot casting mold. My grandfather barely scrambled out of the way of the the swinging tons of hot steel, and he lost part of two fingers of the hand he had thrown up to protect himself. According to my father, my grandfather’s severed fingers were placed in a paper sack, and he was given a nickel for the trolley and told to take himself to the hospital. “Can you believe it?” my dad would say, offering this story repeatedly over the years as an archetypal example of how the “little guy” got screwed. Scoffing at this account and reasserting his own respectability, “Little Grandpa” insisted he had been brought to the hospital in a proper ambulance. Nevertheless, Valley Mould was nicknamed “Death Valley” at this time, and my grandfather could tell stories of men he had seen die. One friend of his had fallen when crossing a plank catwalk across an enormous vat of hot sand. The man succeeded in grasping the chain my grandfather threw down to him but suffocated before they could pull him out. My father said that the man’s body was shriveled up from the heat. My father said it had taken a long time for my grandfather to get over it. Not surprisingly, “Little Grandpa” was an ardent supporter of the unions. “You better believe it,” he’d say. He even used to take my father, when he was five or six, to meetings at a tavern called Sam’s Place where steelworkers from the smaller steel companies and their supporters, who were fighting for the right to unionize, would gather in the days before the Memorial Day Massacre.

[blocktext align=”left”]My grandfather conspired with his supervisor to arrange a draft deferment. “Hell yes!” he snorted. “What would I wanted to go to any shitting war for?”[/blocktext]Yet “Little Grandpa’s” stories were just as challenging to beliefs on the left as my great-grandfather John’s were to those on the right that celebrated America as the land of opportunity. While he fought passionately for his scrap of the pie, he had no time for social causes or political ideology that went beyond a decent wage and a measure of respect. Unions were important to him because with the “big guys” in control “you need a little something to show,” a statement with an implicit hint of violence. When I tried to get him to talk about the terrible conditions in “Death Valley” that I had been reading about in history articles, however, he impatiently insisted that “it was all right” and took me down to his workroom to proudly show me the gadgets he had forged with scrap metal during his downtime at the foundry. He was far more interested in discussing the intricacies of ingot molds that the social conditions of the mills. My grandfather’s stories were also shorn of idealistic notions of bravery and patriotism that laced the mythic narratives of both the Right and Left in the United States. When I asked my grandfather what he had done on the fateful Memorial Day when the police starting shooting at the protesting steelworkers and their supporters, he looked at me as if to determine whether I was a fool and spat, “What d’ya think I did? I turned around and ran like hell!” When I asked him why he hadn’t fought in World War II, he boasted that, after receiving an induction letter, he conspired with his supervisor at Valley Mould to get shifted to the job of crane operator, a category of worker for which the superintendent could claim a deferment. “Hell yes!” he snorted. “What would I wanted to go to any shitting war for?”

[blocktext align=”right”]Like many in my family, “Little Grandpa” also never lost the profound ethnic and racial hatreds that characterized the mill neighborhoods, and he never privileged the plight of “the working man” over such prejudices.[/blocktext]Like many in my family, “Little Grandpa” also never lost the profound ethnic and racial hatreds that characterized the mill neighborhoods, and he never privileged the plight of “the working man” over such prejudices. Over Sunday dinner, he banged his silverware and told how in the old days if you were dating a girl whose families were “bohunks” (Bohemians) or “hunkies” (Hungarians) and you strayed over the wrong side of Ewing Avenue, you’d “better watch out, you’d better believe it!” When I went to say good-bye to my grandfather before leaving for a college study abroad program in Greece, his parting words were, “You watch out for those dagos over there.” I smart-mouthed back that there were no dagos in Greece. “Dagos, spics, whatever, they’ll get you every time,” he glared ferociously at me. In a place where ethnic animosities had long been fed by company practices of hiring the most recent immigrant arrivals en masse as strikebreakers or using them to lower the wages of existing millworkers, ethnic divisions were a profound source of contention as well as of identity and support in my childhood world. As is clear from my grandfather’s stories, various factions of European immigrant and native workers had fought among each other before they turned on Mexicans, and later, African Americans as the latest entrants into the mill neighborhoods. The bitterness of such divisions is epitomized by my first distinct memory of a black person. I imagine I was about four or five years old at the time and holding my mother’s hand. Near the Swedish Lutheran church we attended, two white neighborhood boys were chasing an African American teenager with a pipe; they were clearly intending to beat him senseless for daring to cross neighborhood lines that were as rigidly enforced as any national border. It was the same hatred that in later years would cause a troubled teenage cousin from my father’s side to go off into the woods with his biker buddies and machine-gun portraits of Chicago’s first black mayor, Harold Washington. How does one talk about such hatreds without resurrecting every stereotype of the white working class? How does one lash together an understanding of a man like my “Little Grandpa,” would would both spout vitriolic hatred and watch reruns of Little House on the Prairie on television, TV dinner sitting on his lap, tears streaming down his face, transfixed by nostalgic memories of his own rural upbringing.

[blocktext align=”left”]”Little Grandpa” was banned for life from the local Ace Hardware for pulling a penknife on a smart-mouthed employee.[/blocktext]During college, I valorized the parts of my grandfather that accorded with romantic leftist labor narratives—his work in the foundry, his union activities and presence at the Memorial Day Massacre. I conveniently tried to ignore those aspects that would make my liberal college friends cringe. (Secretly, I doubted whether most of my college friends would actually like “labor” if they met them in person.) Yet I loved talking to my grandfather. It was almost like stepping into a time machine. He often spoke and acted as if it were still the 1930s. And it wasn’t simply a sign of old age; from what everyone said, he had been like that his whole life, as if his world had been arrested at some point when he was in his twenties. Once in the 1990s, outside a neighborhood restaurant on one of Southeast Chicago’s main drags, he only half-jokingly pushed my future husband into the shadows of a storefront as a police car drove by. “Watch out. It’s the flivver squad,” he said in an undertone, as if it were still the Al Capone era and they were young punks afraid of the cops chasing them and knocking their heads together. He remained feisty until the end. My mom called me once when “Little Grandpa” was in his eighties and told me in an exasperated voice how he had been banned for life from the local Ace Hardware for pulling a penknife on a smart-mouthed employee. A few days before he died at age ninety-two, he expressed his impatiences to see deceased loved ones once again in the afterlife. He irritably instructed my sisters and myself to help him put on his best suit, then lay down on the bed to await his death.

[blocktext align=”right”]Like a domineering family member about whom one feels profoundly ambivalent, the steel mills were both frightening and something upon which everyone depended.[/blocktext]My grandfather’s life, like those of many in Southeast Chicago, had revolved around the steel mills and the social worlds the mills had helped to create. The steel industry was the reason everyone had been brought together. Like a domineering family member about whom one feels profoundly ambivalent, the mills were both frightening and something upon which everyone depended. Craning my neck from the backseat of our car as we drove past the mills, I would, as a child, try to catch a glimpse of the fires blazing in their innards. There was a stark, overwhelming beauty to the enormous industrial scale of the mills, with vats the size of houses pouring molten rivers of golden steel while gas jets flared through the nighttime sky. At the same time, it was impossible to escape the sooty air and the less toxic visible waste that seeped from heavy industry into the ground and the surrounding river, wetlands, and lakes where I used to go skinny-dipping as a teenager. The steel mills and the union wages the mills paid after World War II had raised both sides of my family—the respectability-seeking immigrants as well as the hard-scrabble white poor—to a stable, almost “middle-class” prosperity. Even my Big Grandpa, for all his supposed regret about immigrating to the United States, enjoyed a degree of economic security in the second half of his life that contrasted sharply with the hardships he had known as a child. While the stories my relatives told sometimes resonated with and sometimes challenged the dominant societal narratives that threatened to overshadow their own, there was a continuity and stability to this world. There was, in both the Calumet region and in the United States as a whole, a widespread belief in future prosperity for oneself and one’s family and a sense that both factory owners and workers were bound in a common enterprise that linked them indelibly to places like Southeast Chicago. ::

Don’t forget to visit the Exit Zero Kickstarter.

Do you like what we do here at Belt? Consider becoming a member, so we can keep delivering the stories that matter to you. Our supporters get discounts on our books and merch, and access to exclusive deals with our partners. Belt is a locally-owned small business, and relies on the support of people like you. Thanks for reading!