By Wesley Raabe

Editor’s note: You might be wondering what the letters of Walt Whitman’s mother have to do with Cleveland or the greater Rust Belt. There’s a simple answer: Wesley Raabe, the editor of the Louisa Van Velsor Whitman letters, teaches and researches at Kent State, right here in Northeastern Ohio. But there is also a Rust Belt aspect to Louisa’s letters. The ways we stay connected with our offspring, over time and space and a cultural divide—may resonate for anyone of a certain age keeping tabs on kids, family, and friends who live far away, via Facebook or any of the countless, fragmented modern modes of connecting. Louisa sent her letters from Brooklyn to her son in Washington, D.C.: she reads, reacts, and chatters back at local news, worries about the economy and her own finances, and shares stories of interest with her son in her letters in a way that is utterly recognizable today.

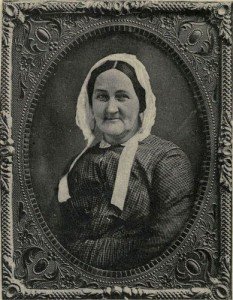

In much of the 20th century scholarly criticism of Walt Whitman’s work, the poet’s admiration for his mother, Louisa Van Velsor, represented a stumbling block. Edwin Haviland Miller, editor of Whitman’s multi-volume Correspondence, referred to her “nagging querulousness” and “emasculating rule” over the family. Miller’s characterization drew heavily from Louisa’s letters; her writing is often summed up as “complaints.” In the eyes of esteemed literary critics who followed Miller, including Larzer Ziff and Paul Zweig, Walt’s “illiterate” or “semi-literate” mother was cast as a psychological burden that the poet had to overcome.

I was dimly aware of this scholarly tradition when Kenneth Price, co-founder of the Walt Whitman Archive, suggested some six years ago that I edit Mother Whitman’s letters: it seemed like a dreary prospect despite his assurance that Louisa Van Velsor was not the termagant of scholarly lore. Price sought to pique my interest with the challenge of the editorial work—her letters are known for lacking punctuation, and most are undated—and he explained that more sympathetic reading of the poet’s mother had become the new consensus among Whitman scholars. Extended quotations in newer scholarship show that her letters are not unrelieved litanies of complaints. This new consensus deserves wider public dissemination, and I’ve contributed to that effort by publishing the letters of Louisa Van Velsor Whitman on the Whitman Archive.

I did not expect a sainted Victorian mother—Walt tried to beatify her when he described Leaves of Grass as the “flower of her temperament active in me”—but neither did I expect a highly engaged mind, fully conversant with the periodical culture of her day. In seeking to date her letters accurately, I chased down Louisa’s mentions of people and everyday events in her beloved Brooklyn, often from the now-digitized Brooklyn Daily Eagle and the New York Times. Her reading of the Eagle is intriguing because she often mocks its political bias toward the Democratic Party. I eventually began to think of Louisa as like a present-day Republican whose TV is forever stuck on MSNBC—or a Democratic partisan whose remote-hogging husband keeps the channel tuned to Fox News.

She read the Eagle’s political news often against its rhetorical grain. Her sympathies fell with the Republican Party for two reasons. First, her son George Washington served as a contractor for a public corporation under the auspices of a local water board, which drew the ire of the Democratic Party; and, second, Walt served as a clerk in the office of the Attorney General for three Republican presidential administrations. Because she was dependent on her sons—her husband Walter, Sr., died in 1855, and there was no Social Security or pension for her—Louisa’s own financial well-being was beholden to the sprawling workforce of activist local and federal governments, which during the Civil War and Reconstruction were associated with the Republican Party. Identifying with the working class and dependent upon her sons, Louisa Whitman’s letters show an astute critic of political rhetoric that conflicted with her own interests and sympathies.

Louisa never relied on a single source of national or local news—Walt forwarded periodicals regularly. When living with son Jeff and daughter-in-law Mattie during the Civil War, Louisa read both the New York Times, the Herald, and other city papers—but the Eagle was her most familiar source for local news. It was an old acquaintance, which she had followed at least since Walt had served as the paper’s editor from 1846 to 1848. Between 1860 and 1872, she cited its city news and politics and its local gossip; its national and European dispatches; and, whenever her housing was unsettled—such as when Jeff departed to St. Louis to serve as a civil engineer in 1867—its advertisements for lots or rental houses.

The Eagle, under its longtime editor Democrat Thomas Kinsella, was no friend of the Water Board nor of the Republican presidential administrations under which Walt served. Should either of Louisa’s most reliably supportive sons suffer economically, George from the vagaries of the housing market or from upheavals in local water politics or Walt from Johnson’s impeachment or Reconstruction politics, Louisa’s financial support could dry up and render her destitute. George mostly took responsibility for Louisa’s housing after Jeff’s departure for Missouri, and Walt sent regular money orders for major household purchases (a couch, a dress, a winter’s supply of coal) and enclosed with his letters small cash gifts for groceries and sundries.

With a nest egg built from his officer’s salary—carefully husbanded for him by his mother, though he was unfailingly generous toward her during the war—George Washington Whitman partnered with a carpenter and a mason to go into business building homes. But the construction trade, during the alternately moribund and frenetic economy of postwar demobilization, produced much financial stress. Within a year of the war’s end, George diversified and began to engage in pipe inspection. Louisa monitored the economic vagaries that buffeted her son George, and she helped coordinate on George’s behalf a series of emergency loans from his brothers that helped him to weather a particularly moribund period from summer 1868 through spring 1869.

[blocktext align=”left”]“i hadent one cent and i asked georgee to give me 50 cents and after looking for a considerable time he laid me down 50 cents well Walt i felt so bad and child like i cried because he dident give me more”[/blocktext]Despite Walt’s urging that his mother spend more freely from George’s pay to care for herself and for three of Walt’s other brothers, including Andrew, who died in late 1863, Louisa resisted, in part because she feared George’s salary could be consumed by caring for her mentally unstable eldest son Jesse and for her physically impaired youngest son Edward (“Edd” or “Eddy,” variously). Louisa had a reserve of a few hundred dollars at the start of the war, but within months of the war’s end she realized that her efforts to reserve George’s pay for him had made her dependent. In December 1865, she lamented, “i dont have much money to spend now adays to think i was such A fool as to use all the money i had in the bank and save the other now i want it and wish i had saved my own.” Her means exhausted, she broke down in frustration when George proved ungenerous: “i hadent one cent and i asked georgee to give me 50 cents and after looking for a considerable time he laid me down 50 cents well Walt i felt so bad and child like i cried because he dident give me more.” Nonetheless, with George’s assistance for housing and Walt’s generosity—Jesse was committed to an insane asylum in late 1864—Louisa soldiered on caring for herself and for Eddy.

One of Louisa’s most stressful moments came in April 1869, when a new board of water commissioners was appointed, an arrangement that prompted Moses Lane, chief engineer at the Brooklyn Water Works and patron of George’s work as a pipe inspector, to reassess his affairs. As she described the new arrangement to Walt, Louisa linked George’s financial expectations with his connections to Lane:

George has gone back to mellville for a short time but will come to camden as soon as he gets the man lane sent out to mellville instructed mr Lane said he must stay a week) i suppos[e?] you saw the change in the commissioners the new ones has the power to turn out or take in i suppose they are northrop and fowler they are the old board and the two new ones is archibald bliss and the eagle man you know his name Walt quinsella or something like it two democrats and two republicans) mr Lane told George in confidence he was making preparations to settle up affairs he couldent tell how matters would turn out) but george said he dident think lane expected it but i suppose he wanted to be ready

The absence of punctuation and phonetic spelling present some challenges, but her meaning can be made out. Millville (Louisa’s Mellville), like Camden, was the site of a foundry: George is training another man to inspect pipe for Lane. But the new water board has raised Lane’s anxieties and thus Louisa’s own. Before this reorganization, the Water Board was shielded from local city politics. But from April 1869 forward, the new Water Board and its four political appointees, all selected by city government, would be more responsive: two Republicans (Daniel L. Northup and Archibald M. Bliss) and two Democrats (William A. Fowler and the “eagle man” editor Thomas Kinsella). Brooklyn property owners, who saw Democrats as their allies and Republicans as a foe weighing them down with property taxes that supported political sinecures, had reached the end of tolerance for an independent Water Board, whose more visible expenditures (outside reservoirs and sewers) included a wide range of street maintenance: lighting, paving, sidewalks, and street cleaning. The new board worked aggressively to reduce property taxes, by taking aim at what Democrats considered a bloated workforce.

[blocktext align=”right”]“mrs stears was here the other day she dont seem to get along very well her son is discharged from the water board with many others there is very many out of employment this winter”[/blocktext]Moses Lane departed the Water Works in spring 1869, shortly after the new board was seated, and new anxieties about George’s employment appear in Louisa’s letters. In June, she reassured Walt and herself about George’s prospects: “he [George] dont think the changes in the water department will make any difference to him it was one of the ring that wanted the republicans put out but the commisioners or some of them wouldent comply.” Earlier that month, the Eagle had published an appeal by a Democratic committee for a list of Republican employees of the Water Works, which it sought to replace with Democrats. Though this effort was too ham-handed, the new board’s pressure proved much more effective the following year. Mass layoffs began in November with a series of employee purges: 100 on November 1; 150 on November 15; and 200 on December 1, with more planned for January (“Two Hundred Men Discharged To-Day,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 2, 1870). In early January, the Eagle lauded an address by Mayor Martin Kalbleisch, who blamed the proliferation of community boards for extravagant expenditures (Brooklyn Eagle, January 4, 1871, 2). For Louisa, these layoffs hit close to home. Her former neighbor Margret Steers dropped by with news about her own son Thomas: “mrs stears was here the other day she dont seem to get along very well her son is discharged from the water board with many others there is very many out of employment this winter”

Louisa’s fears for both George’s fortunes and her own finances would ease because George transitioned away from the speculative housebuilding business after he sold several homes. Despite the new political order, George was able to string together a series of pipe inspection jobs from periodic contracts with the Water Works well into 1872, by which time he had married his longtime sweetheart (Louisa had called Louisa Orr Haslam, her future daughter-in-law, George’s “somebody”) and moved to Camden. Though George’s efforts to secure inspection contracts became frantic in late 1872, the same year that his mother had moved to Camden to stay with him, he had achieved comparative economic success already and planned to build a handsome new house. Louisa’s letters over her last years in Brooklyn mention often George’s recently completed work or prospects.

Louisa’s most amusing comments on the Eagle concern national matters, in which the Democratic-leaning paper—which was derisive toward the Republican impeachment of Andrew Johnson and the candidacy of Ulysses S. Grant—carried water for its own candidates and causes. In February 1868, Louisa addressed the recent impeachment of Andrew Johnson:

we have lived to see something that never was i suppose known before in america the impeachment) i think it rather sad but notwithstanding exactly as it should be i suppose the excitement at washington is far greater than here the copperheads here is all for fight that a war will be the result some great politician down town wanted to bet yesterday that the impeachment would not take place so our georgey took him up told him he would bet him that andrew Johnso would be impeached in ten hours from that time

[blocktext align=”left”]”the old eagle how i dislike it”[/blocktext] Despite some hesitation, she agreed with George, who would have won his bet: Johnson was impeached the next day. Later the same month, Louisa excoriated Kinsella’s Eagle for its misleading news and editorials on Johnson and the expected Republican presidential candidate Grant: “the old eagle how i dislike it yet i take it if i dident see any other paper i should think andy was perfection and all the rest was crushed general grant in the bargain) he must be a bad man.” To discern her intent is a bit of a challenge, but my sense is either that President Johnson is the “bad man” because the Eagle defends him so fervently or that Grant is the “bad man” from the Eagle’s misleading editorial slant.

A similar challenge is offered in one of the most intriguing but difficult-to-understand passages in her letters, from mid-May 1868, near the close of Johnson’s trial in the Senate:

Edd came up stairs yesterday towards evening before the eagle came the eagle came down stairs and the man i think is a democ[rat?] he said to Edd the radicals were all down or something to that affect so eddy came up like mad saying they had cleared the bugge[rs?] and he would never have any thing more to doo withe them i how doo you know he is clear he said it was in the eagle that it wou[ld?] be better to have no congress at all than to doo as they had it was quite amusing to see eddy is such a gale but when i got the paper i see how things were)

Louisa is somewhat ambivalent on whether Johnson should be removed from office, yet the Democrat who declared that the “radicals [i.e., Republicans] were all down” has upset Louisa’s son Eddy, who shares political leanings with her and George. Yet she is reassured by what she sees as a more reliable guide to the impeachment trial in the printed Eagle. Perhaps the Eagle helped persuade her that Johnson’s impeachment was a step too far, but she balanced some trust for its reports of the news from Washington with ongoing skepticism about its political coverage.

Her skepticism was more prominent later that summer, after Walt sought his family’s opinion on the Democratic presidential nominee Horatio Seymour, former governor of New York, and his running mate Francis P. Blair: “How do you all like the nomination of Seymour and Blair?” Instead of answering directly, Louisa commented on the Eagle’s coverage of Seymour’s return to Utica in its July 14, 1868 issue, an article entitled “Seymour among the People.” The former governor, lauded there as “New York’s most distinguished statesman, and the next President of the United Republic,” was said to be greeted by enthusiastic crowds as his train neared his hometown and upon his arrival was celebrated by all: “Where Seymour is known best, he is beloved most, and at Utica, his home, an ovation awaited him in which the citizens without distinction of party seem to have joined” (italics added). The Eagle made no pretense to balanced political coverage: even to name the party “Republican” was to convey too much respect. The term “Radical” was its preferred term, but for Louisa this fawning report on Seymour was more befitting a comedy routine: “o walter the nomanation aint it great i wish you could see the eagle it is worse than ever all the respectable radicals is in favor of seymore the eagle says they are nearly all copperheads around here.” Seymour would carry the popular vote in the state of New York, but Louisa delighted in the national returns: “best of all is grant is elected.”

[blocktext align=”right”]“you remember Walt i always said if Grant got to be presedent i hoped he wouldent disappoint his party but i dont know i hope he wont but i suppose time will tell”[/blocktext]Grant’s election allayed temporarily but did not end Louisa’s anxieties, and I close with one more episode in which her reading of postwar purges of federal employees struck her quite differently than it was described in a newspaper. This time she read of executive branch dismissals in the New York Times. In March 1869, an article detailed the “Great Reduction of the Clerical Force in the Departments—Discharge of Female Clerks,” a reduction which threatened also Walt and his close friend William D. O’Connor, who was employed by the Treasury Department. According to the report, the Printing Bureau was expected to terminate seventy female and fifteen male employees by month’s end. In the Government Printing Office, seventy-five employees, designated in the article as “females,” were to be discharged from the folding room. An unstated number of “females” were also to be discharged from the bindery. The dismissals were to come, according to the paper, “from the least efficient and most obnoxious, politically, of the employes [sic]” (March 28, 1869, 1). The article confirmed Louisa’s anxieties, as it called to mind concerns that she had voiced earlier about Grant as a potential president: “you remember Walt i always said if Grant got to be presedent i hoped he wouldent disappoint his party but i dont know i hope he wont but i suppose time will tell.” Walt’s friend O’Connor and Walt himself retained their appointments, but the reminder that so many female employees had lost a tenuous financial hold struck Louisa as a fact to be lamented rather than celebrated. Though not ready to surrender hope in the new Republican president, the dismissals that the Times lauded have a different tenor in her postscript note: “i felt sorry to see so many females discharged.”

Walt would call his mother “illiterate in the formal sense,” but she achieved functional written literacy and some moments of quite powerful verbal expression. Moreover, her reading in the print culture of her day was sophisticated and critical. She was not learned, but she applied a rough and ready wariness to resist the verbal manipulations of party politics. Louisa Van Velsor Whitman was one of the first to recognize and admire the poet with a just claim to being one of America’s greatest and a champion of democratic self-expression, in large part because Walt was her son. Her letters also capture a sharp working-class wit deflating the media bias of her day.

Wesley Raabe is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at Kent State University. He is the editor of “walter dear”: The Letters from Louisa Van Velsor Whitman to Her Son Walt, an edition of 170 letters and full biography that is publicly accessible on the Walt Whitman Archive. He also posts links and short letter excerpts on Twitter as @MotherWhitman. The complete run of the open-access Brooklyn Daily Eagle is available from the Brooklyn Public Library.

Do you like what we do here at Belt? Consider becoming a member, so we can keep it coming. Our supporters get discounts on our books and merch, and access to exclusive deals with our partners. We are a locally-owned small business, and rely on the support of people like you. Thanks for reading!