By Sam Gringlas

On a rented yellow school bus ambling east on I-69, Hudie Langston shifted in his vinyl seat, turned toward the two women chatting nearby, and said what a lot of people in Flint have been thinking for months.

“We’re not getting anything but band-aids,” he said.

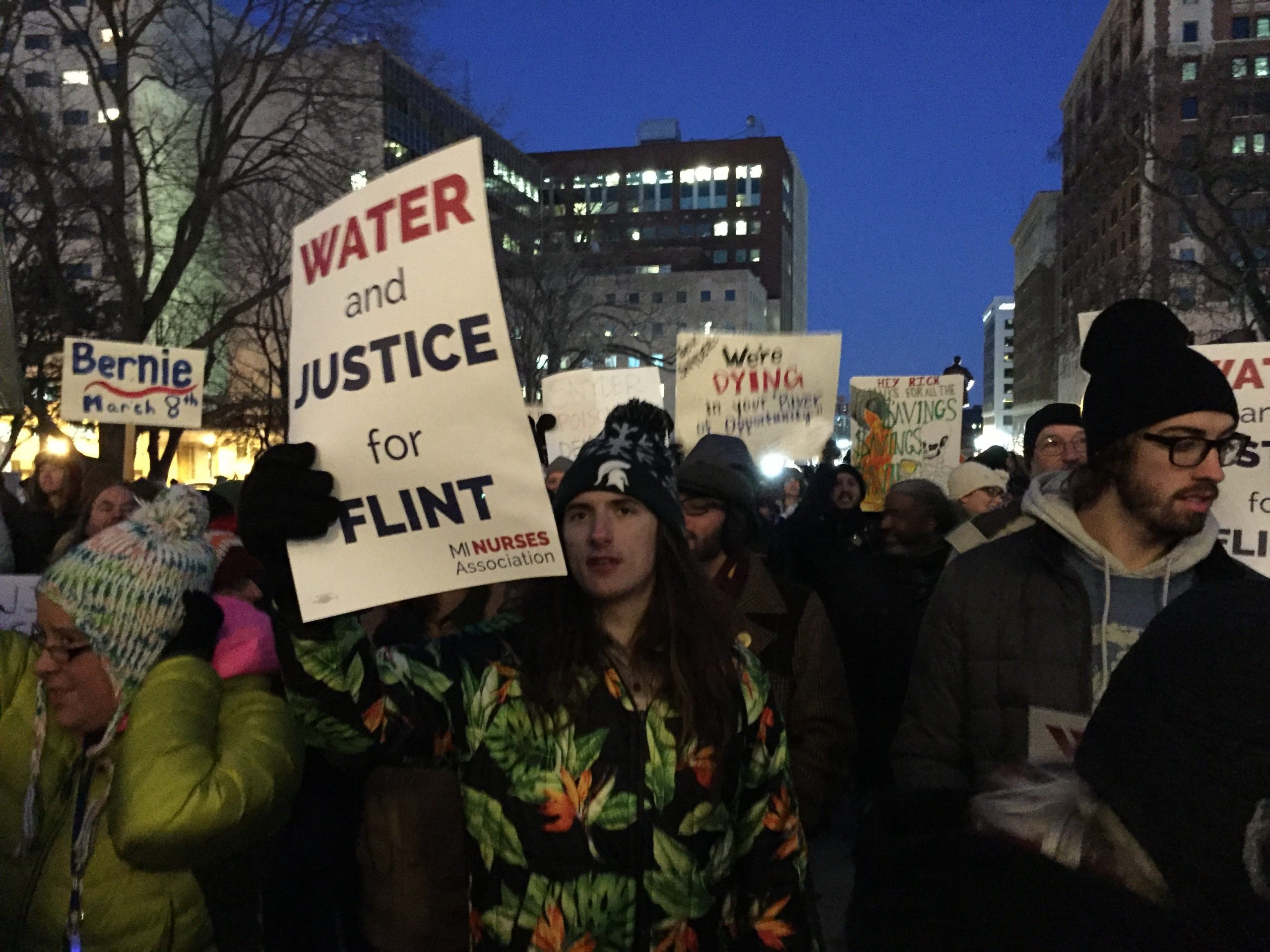

It was January, and Langston was one of a few dozen Flint residents who had boarded a bus headed for Lansing to join several hundred others in protesting Gov. Rick Snyder’s State of the State address. In hats, scarves and gloves, they came dressed for the cold and angling to call foul on the governor and his administration for their handling of the water crisis.

By then, three months had passed since the city of Flint stopped sourcing its water from the Flint River. Analysis conducted by a local pediatrician back in October tied elevated blood lead levels in children to the city’s drinking water, confirming what many residents had known for more than a year: the water was unsafe to drink.

By then, three months had passed since the city of Flint stopped sourcing its water from the Flint River. Analysis conducted by a local pediatrician back in October tied elevated blood lead levels in children to the city’s drinking water, confirming what many residents had known for more than a year: the water was unsafe to drink.

Back on the bus after the protest, Langston and the others no longer held onto the hand-lettered “Save Flint Now!” signs they proudly displayed on the ride up and sat quietly in the darkness of the bus.

Connie McNeal and Connie Edwards, the two women sitting near Langston, hadn’t met before, but soon were swapping stories and tips about coping with the water crisis as the bus made its way back to Flint. McNeal said she was showering normally, but still used bottled water to cook and drink. Edwards was worried about legionnaire’s disease. Langston said both he and his wife had their blood tested for lead poisoning, and they’re okay.

[blocktext align=”right”]“I live here because I love my city. I could live anywhere I want to live…I live in Flint because I want to live in Flint. If everybody leaves, then what are we going to have?”[/blocktext]The conversation went on like this. Langston said the whole thing reminded him of the infamous syphilis study at Tuskegee. Edwards said one of the girls at work told her drinking V8 juice and eating peanut butter could help combat the effects of lead poisoning. She wondered if her nephew has been tested. Langston doubted he’d be able to sell his home. McNeal, who runs a small business taking care of elderly people, said many of her client’s children have pulled their parents out of Flint. The bus riders talked about Flint’s new mayor, Karen Weaver. Maybe she can fix this, they said.

But soon, discussion of water subsided. The talk turned to other things: unemployment, gun violence, schools, youth, factory jobs, poverty.

“I got two kids in Vegas and two in Atlanta,” Langston said. “They all want me to move.”

“I got that call, too,” Edwards added, nodding knowingly. “Our city is broken.”

“I live here because I love my city,” Langston told the group. “I could live anywhere I want to live. My wife is a doctor; I’m retired from General Motors. I live in Flint because I want to live in Flint. If everybody leaves, then what are we going to have?”

The water has certainly drawn the city into crisis, but Flint’s residents face a bucket of other challenges, some of which have plagued the city and its people for years, long before Flint Water Crisis ever trended on Twitter. The state has cited several schools as some of the lowest performing in Michigan. Flint frequently appears on lists of the nation’s most violent cities. Few major grocery stores remain open in city proper. The unemployment rate is nearly double the state’s.

The water has certainly drawn the city into crisis, but Flint’s residents face a bucket of other challenges, some of which have plagued the city and its people for years, long before Flint Water Crisis ever trended on Twitter. The state has cited several schools as some of the lowest performing in Michigan. Flint frequently appears on lists of the nation’s most violent cities. Few major grocery stores remain open in city proper. The unemployment rate is nearly double the state’s.

For all the focus on water, far less attention has been given this host of other challenges. If all the city gets are band-aid fixes, as Langston says, then it makes sense to ask why so few policymakers are considering what real, game changing solutions would look like. Talk with Flint residents and, like Langston, Edwards and McNeal, many will tell you real solutions have got to go deeper than pipes, water bottles and filters. Ensuring clean water is critical, and that’s certainly the most pressing challenge right now. But it’s not enough.

On the bus, the conversation starts with water, as it does in so many community meetings across Flint and for a brief while, on front pages of the national press. But on the freeway between Lansing and Flint, the discussion spins out, snowballing into something bigger.

Edwards has six close friends. She told the group how they’ve all lost a son or daughter to gun violence. Langston and McNeal nodded. They understand. Langston lamented gentrification downtown, and McNeal, a teacher, talked about students who can’t afford basic necessities, like underwear.

“There are good people in Flint, very good people, hard working people who want to work and want jobs and don’t want handouts,” McNeal said. “And those who are not what you call productive citizens; they just lost. The hope is gone. Because when you’re surrounded by that type of economic disadvantage, it does something to you mentally.”

Everyone wants to talk about Flint’s water, but what remains to be seen is whether what happened in Flint will galvanize a broader conversation about life in American cities. When will people start talking about the kinds of things Langston, Edwards and McNeal worry about — the realities of everyday life in so many hard-hit cities across the Rust Belt? And here, in Flint, what happens to all the efforts of nonprofit leaders, teachers, pastors, neighborhood organizers and community organizations who were already trying so hard to push back against a narrative colored by decline, especially now that their city has become best known as the place where the water was poison?

Amid crisis, a community presses on

Spend an afternoon driving around Flint, and it becomes increasingly clear that an accurate depiction of the city can’t solely rely on its reputation as poster child of post-industrial decay.

On a driving tour of the city led by Heidi Phaneuf, a bespectacled official with the Genesee County Land Bank, several neighborhoods are dotted with new community gardens, modest Habitat for Humanity homes with broad front porches, and neatly kept Victorians more than a hundred years old.

In neighborhoods like Grand Traverse and Carriage Town, those places closest to downtown, Phaneuf points out some form of a community center or a well-maintained park every couple of blocks. There’s Oak School, a formerly vacant elementary built in 1865 that a developer turned into low-income housing for seniors. There’s a restored wetland. A riverside trail. An outdoor recreation space is taking shape on a massive site formerly home to Buick City, the General Motors plant that once provided thousands of jobs in Flint. It’s late May and the sound of chirping birds, lawn mowers, and electric tools float in through the car’s open windows.

Heading east and away from downtown, vacant school buildings hulk on several street corners. Houses are burned out. More are boarded up. Grassy lots fill in where homes once stood. In Flint, one out of every eight residential properties still requires demolition, according to the city’s blight removal plan. The figure is one in eight for commercial properties.

Heading east and away from downtown, vacant school buildings hulk on several street corners. Houses are burned out. More are boarded up. Grassy lots fill in where homes once stood. In Flint, one out of every eight residential properties still requires demolition, according to the city’s blight removal plan. The figure is one in eight for commercial properties.

“This was the school that everybody went to,” Phaneuf says, motioning toward an empty structure off to one side of a broad, leafy boulevard in the Civic Park neighborhood. “It’s vacant now. All around this U-shaped drive, there’s maybe three residents.”

With a new master plan, blight elimination framework and federal demolition funding in hand, Flint has made headway in tackling blight and stabilizing neighborhoods and continues to do so, despite the water crisis. The land bank has demolished 1,080 vacant homes to date and is on pace to do 900 more by the end of 2016. Kettering University has also developed its own initiative to purchase and redevelop blighted properties. But little funding exists for redevelopment efforts or commercial demolitions, leaving many places, particularly those distant from the city’s core, largely untouched. Removing the entirety of the city’s blight over the next five years will cost an estimated nearly $108 million. As of February, the city was nearly $98.3 million short of that goal.

Neighborhood associations have tried to make changes on their own, such as in Civic Park, where a local pastor has led efforts to plant clover on empty lots and board vacant, land bank-owned homes with vinyl coverings that look like real windows. But those efforts are only temporary fixes, and in the absence of sufficient funds, bringing the neighborhood back to life is a long way off. Not every neighborhood will again look like it once did, either. As in many shrinking cities, some neighborhoods are slated for futures as urban forests, farmland or other uses.

“The idea of the blight elimination framework is you have to make these tough choices,” Phaneuf says. “You can’t take care of all of the needs, but how can you take care of as many needs as possible.”

Lu

Christina Kelly, the land bank’s director of planning and neighborhood revitalization, says that so far, the water crisis has not impacted funding for demolitions, since most of those dollars come from the federal government. Surprisingly, the average sale value of a single-family home in Flint has also increased. According to the Michigan East Central Association of Realtors, the average sale of a home was $30,028 during the first quarter of 2016, up from $17,743 during that time last year. The land bank attributes that rise, in part, to the success of blight removal efforts. However, it’s still not clear whether the water crisis will affect home sales in the long run.

Phaneuf says some foundation funding initially being considered for expanding blight removal efforts was reallocated after the onset of the water crisis. The C.S. Mott Foundation, for example, contributed $4 million of the $12 million needed to finance the city’s switch back to the Great Lakes Water Authority. Foundation officials say Mott was in talks to expand funding for some existing initiatives, like blight removal, and some of that money was re-targeted as part of the water crisis response. However, the majority of the funding dedicated for the water switch came from outside that year’s planned program budget and no existing funding pledges were broken as a result.

“A lot of people did shift a lot of their focus, and the foundations did as well, but the neighborhood groups were still doing a lot of their own work while all of this was going on,” Phaneuf says.

Neal Hegarty, vice president of programs at the Flint-based Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, which devotes millions of dollars annually to local economic development, arts education and health initiatives and has played a major role in providing wrap-around services in light of the leaded water, said the foundation community is working hard to retain and bolster efforts in other areas, even amid the water crisis. The foundation plans to invest an additional $100 million in Flint over the next five years, half of which will be allocated this year. For comparison, Mott spent $40.9 million in Flint in 2015. That money will support ongoing initiatives, as well as help expand early childhood education and community health initiatives related to the water crisis.

“The community has faced a lot in the last couple of decades, and this did not happen in a vacuum, so while we need to focus on the water, we need to focus on the lead, we still need to focus on all of the underlying and other issues and challenges and opportunities that the community has had, even outside of the lead,” he said.

At the Brownell-Holmes STEM Academy, a unique community education program already in place helped school officials deploy critical resources to support families when their water became unsafe.

The Community Education Initiative is a strategy now employed by four buildings within Flint Community Schools. The approach emphasizes project-based learning and connects students and parents with area nonprofits and other community resources, such as health services and after school programming. Community education, perhaps most importantly, envisions the school building as a community hub.

The approach is not a new one. It was first developed in Flint back in 1935. But as the city emptied out, funding such an initiative became challenging and the program eventually disappeared. With funding and staff from local foundations and nonprofits, as well as several dozen community partners, the school district and the Crim Family Fitness Foundation resurrected community education in 2014 with Brownell-Holmes as the pilot. The program is on track to expand to every public school in Flint by next year.

With that infrastructure already in place at Brownell-Holmes, Kerry Downs, a former teacher and the academy’s director of community education, said the school was better equipped to respond to the new challenges created by the water crisis.

“In addition to the water, which we know is an ongoing issue and there is not any clear solution in the near future, what this has done is exasperated the other needs that many of our families have because they have had to shift their focus to making sure they can procure clean water,” she says.

While teachers have a front-row seat to the needs of their students, they often don’t have the time or resources to address needs beyond academic ones. The community education initiative aims to fill that gap. This year, a teacher at Brownell-Holmes noticed a student stopped wearing his glasses to school. When she asked why, he said they broke. The teacher alerted the community education office, who reached out to the kid’s mom. What they learned: she wasn’t able to afford a replacement pair. No problem. The staff connected the parent with a local organization that could help, and followed up to make sure the kid got his glasses.

Downs says these kind of scenarios play out all the time. However, program staff are still in the early stages of developing an evaluation framework, which will provide a more definitive picture of how well the initiative is doing at improving attendance, third-grade literacy levels, high school graduation rates and engaging the community. Since its launch at Brownell-Holmes, the initiative has organized three days of after school tutoring every week, engaged a dedicated core of volunteers and established partnerships with 20 community organizations.

The school is working to meet broader community needs as well. Community education leaders helped establish the Brownell-Holmes Neighborhood Association, which now meets monthly in the school, and conducted a walking audit to gauge where better lighting or signage was needed in the surrounding neighborhood. When they asked nearby residents what they wanted to see from the program, many said ensuring basic public safety should be a top priority, and as a result, a liaison from the Flint Police Department is posted on campus to monitor after-school activities once the daytime school security staff have gone home. And that’s not just a concern at Brownell-Holmes. On the bus, Langston, McNeal and Edwards all cited public safety as one of the central challenges facing the city at large.

Downs sums up their concerns this way: “Don’t give us anything else until you’re going to guarantee us that it’s safe.”

On a Wednesday afternoon at the end of May, a hoop house rises from the grass outside the Holmes building, and in a courtyard, newly constructed benches await installation around the school. Triangular and hexagonal planting beds designed, measured and built by students are situated in a row. Colorful signs adorn hallway walls, and though class is in session, a handful of kids pop in and out of classrooms on their way to the bathroom or the front office. There’s an outdoor walking track, conceived and designed by students, for school walking and biking clubs. Neighborhood residents often come here to walk and garden, too.

But even in a space already outfitted with so many community resources and visibly brimming with positive energy, Downs says it’s still difficult to fully insulate children from the realities of the water crisis.

[blocktext align=”left”]“Our job is to make sure our kids know that they are valuable, they are destined for greatness, this is not a hopeless situation.”[/blocktext]When a handful of kids went up to the water fountain last year during a class field trip to the Cranbrook Science Institute in leafy Bloomfield Hills, the other students tried to stop them. Water from fountains is not safe water, they thought. What they didn’t understand was that the water was only unsafe in their school, in their homes and in their neighborhoods. In Bloomfield, the water was just fine.

“That’s what our kids have learned,” Downs says. “How do you explain that to a child, that water is okay in one location, but not in another?”

Some things, like solving a major public health catastrophe, are out of an educator’s control, and Downs says it’s unclear how these experiences will affect kids down the road. But that doesn’t make the work underway at schools like Brownell-Holmes any less worthwhile. If anything, it becomes even more critical.

“Our job is to make sure our kids know that they are valuable, they are destined for greatness, this is not a hopeless situation,” she says. “This is absolutely a situation where we can make smart choices about our health and about the way we are taking care of our kids.”

Across Flint, agencies and organizations are moving ahead with ongoing initiatives to promote change in their city, often while adjusting where needed to fill new gaps cut open by the water crisis.

The Flint Farmer’s Market, which doubled its customer base since moving to a larger, more centrally located facility two years ago, has started offering nutrition classes to help families prepare meals best suited for the needs of children with lead poisoning. In a city with few major grocery stores, access to fresh produce and other healthy foods has become more important. Over the last year, the market has paid out $100,000 to farmers as part of DoubleUp! Food Bucks, a program first launched in Michigan that allows customers to double their SNAP benefits up to $20 when the money is spent on fresh produce at the farmer’s market.

Photo: Amanda Allen

While the market hasn’t resolved conversations about the impacts of downtown development versus neighborhood investment and the extent of their responsibility to expand access to healthy foods in a city widely considered a food desert, Karianne Martus, the market manager, worries the progress will be overshadowed by the water crisis.

“There are people here that are working really hard to make this a better place and that’s the thing that all of us want to make sure doesn’t get forgotten,” she said on a busy Saturday morning from an office above the airy market. “Because what happens is that if everyone thinks that it’s a wasteland, no one’s gonna come here. No one’s gonna shop here, no one’s going to want to live here, they’re not going to send their kids to U of M, or Kettering or Mott. It’s such a fine line to walk because you want to make sure that people know that there’s a lot of things going on here.”

Water crisis aside, Flint is a city still grappling with many of the dynamics playing out in post-industrial cities all across the Rust Belt. Residents of neighborhoods on the fringe are getting antsy, asking when they’ll see the kind of new investment that’s come to downtown and worrying that developers are trying to turn the city into an Ann Arbor or Grand Rapids — the kind of revitalization that could displace longtime residents as young professionals with money to spend snap up downtown housing. The jobs haven’t come back. Population trends aren’t likely to reverse anytime soon. Both of Flint’s high schools are considered priority schools, meaning at some point in the last four years they ranked in the bottom five percent of Michigan schools based on graduation rates and performance in math, reading, science, and social studies. There were 48 homicides in 2015. There are residents like Langston, Edwards and McNeal who, despite the promise of community schools, the city’s blight removal plan, and revitalization efforts downtown, don’t feel their lives have improved much.

“People don’t have hope,” Langston says. “They don’t see no way out.”

“We could get frustrated by the coverage that we’ve had in Flint, that it is mostly focused on the negative, but at the same time, I think it’s justified,” Downs says. “I think that the country deserves to see what’s happened in the city, what’s happened with our kids and our family members in the city, is unacceptable, and there’s no way to caste a positive light on that, so I think there is some reality that we are all outraged at what happened, especially teachers and community members who have invested in this community and feel like they’ve been let down as well.”

At the same time, many of Flint’s residents and organizations also see the situation as a moment to prove that the city and its people are not only resilient, but also optimistic about Flint’s future — and their own.

A broader conversation

In May, the President of the United States showed up in Flint and said he had the city’s back. He drank the water. He met Little Miss Flint, the eight year-old who wrote him a letter and asked for a meeting. At a rally in a high school gym, he touted the federal resources his administration had already deployed here and applauded the efforts of regular folks working to make change. But more notably, he called for the kind of larger discussion people like Langston have been waiting for.

“My hope is, is that this begins a national conversation about what we need to do to invest in future generations,” Obama said. “And it’s no secret that, on this pipeline of neglect, a lot of times it’s the most poor folks who are left behind. It’s working people who are left behind. We see it in communities across the Midwest that haven’t recovered since the plants shut down. We see it on inner city corners where they might be able to drink the water, but they can’t find a job.”

Photo: Luna Anna Archey

In January, Flint began to surface in stump speeches in Iowa and New Hampshire. A Democratic debate televised on CNN was held here, during which both candidates called for the governor’s resignation and promised significant investment in roads, bridges, water treatment plants, and other unsexy civic improvements. MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow organized a town hall at Brownell-Holmes. People were finally starting to talk about updating the nation’s infrastructure.

But will all this focus on Flint really lead to anything in the long run?

“My personal sense is that this moment in Flint and the water crisis has not really galvanized a different conversation around distressed communities,” Hegarty, the Mott vice president, says during a telephone interview. “I think there’s still a lot of folks looking to point fingers at who caused the problem — not just the water problem, but the reason that Flint was in financial distress, and not enough stepping back and looking at what are the big picture policy drivers and economic drivers. Why do we have so many cities and school districts continuously on the brink of insolvency and large swaths of our populations continuing to struggle with poverty?

“I wish I knew how we get that sort of conversation and think about the broader set of what do we want our state and all of our communities to look like, but I really don’t know how we get there. I wish I had an answer to that.”

[blocktext align=”right”]”We often get painted in Flint as being an anomaly or different, but there are cities all over the country that are dealing with similar problems.”[/blocktext]Over decades, a whole host of economic forces, policies and social dynamics — like the laws that determine how property taxes are levied, prevailing attitudes about race and class, the decline of American industrial prowess and chronic underinvestment in education, just to name a few — chipped away at or failed to improve health, well-being and economic mobility, leaving so many cities just trying to hang on.

A report by the Michigan Municipal League, for example, says the state’s municipal financing model is at least partly to blame. During the last ten years, Michigan has used more than $6 billion in sales tax revenues that, according to state statute, were promised to municipalities, but were instead used to fill shortfalls in the state budget. Flint would have received an extra $54.9 million since 2003.

“When you really look at the nuance and the depth of the problem, nothing stands alone and it really is, the whole community becomes kind of an ecosystem, and everything that you change impacts something else,” says Kimberly Roberson, the Flint area programs director for the C.S. Mott Foundation.

“There’s no one thing that needs to be addressed. It all fits as part of a whole.”

Kelly, of the land bank, says she anticipates the national conversation will likely remain confined to infrastructure. The Democratic candidates for president still bring up Flint occasionally, but mostly to talk about water treatment plants, roads and bridges. Downs and Phaneuf say they are hopeful the national conversation will shift, but they’re not counting on it for now.

“We often get painted in Flint as being an anomaly or different, but there are cities all over the country that are dealing with similar problems,” Hegarty says. “And it all comes down to how do we get more jobs in close proximity to where people are, how do we get skills and education levels up so people can better compete in the current economy, and how do we get things like commercially viable grocery stores in underserved communities? All the work that we do is important, but somehow figuring out how places like Youngstown and Flint and Gary and a whole host of cities answer those questions is really important.”

Replace every failing pipeline, road, and bridge in the country and those communities will still be coping with poor schools, blighted neighborhoods, unemployment, and a host of other challenges. With financial aid packages designed to respond to the water crisis stalled in Congress and only recently approved in the state legislature, it seems unlikely the kind of sweeping changes required to adequately begin addressing those issues on a large scale will occur in the near future.

“Of course I hope this terrible tragedy is something people just don’t dismiss as one issue,” Down says. “My hope is that state and federal (policymakers) will continue to identify in a more timely matter the needs of the communities in urban settings and make sure that they’re addressing issues before they become tragedies. I mean that’s my hope, but for now, at community ed, we’re just coming in every single day and making sure we’re doing right by our kids.”

What’s next?

With the driving tour nearing an end, Phaneuf starts talking about what it’s like to live in Flint. Part of her job is giving tours, and it’s apparent this segment is typically on the discussion syllabus.

[blocktext align=”right”]“I think the beautiful thing is that we found out we’re really not separated. If it really was an issue to bring the people together, this was it. Everybody needs water. Black, white, rich, poor, educated, uneducated.”[/blocktext]“You have to invest a lot of your time and energy into the place that you live, like being involved in a neighborhood association, you know you have to spend time going to neighborhood meetings, going to community meetings. You have to spend time working on your neighborhood through cleanups, beautification projects, gardens, advocating for resources for your neighborhood,” she said. “It takes a lot of effort, so a typical actively involved resident in Flint on the weekends will spend at least one day doing community work, where you might spend a day at the lake or cookout; you have to work to keep your neighborhood looking good.”

What about all those residents who broke in or for the first time tried out their activist gloves with the onset of the water crisis? Can all those networks be employed for other efforts?

“It’s possible,” Phaneuf says. “Typically neighborhood groups are geographically focused on their specific area, and the water crisis was more of a large-scale, city-wide, not this neighborhood or that neighborhood, but everybody kind of effort. I hope that some of that takes place, but it’s hard to say whether it would or wouldn’t.”

Rev. Alfred Harris, the pastor at Saints of God Church in Flint, is looking to harness the surge of civic engagement that’s welled up over the water crisis.

“We still have a lot of issues here in Flint,” he says. “We are trying to use this as a springboard, and when all this is over, hopefully we’ll have a template of communication that we can address some of those other issues as well.

“I think the beautiful thing is that we found out we’re really not separated. If it really was an issue to bring the people together, this was it. Everybody needs water. Black, white, rich, poor, educated, uneducated. Everybody needs and deserves safe, clean water and so that caused people to come in from all different spheres, all different levels of government. We all had this one common goal to bring us together, so that’s the good part of it. I wish we didn’t have this situation, but everybody understood we’ve got to work together.”

Photo: Luna Anna Archey

On the Sunday after Easter, the Saints of God sanctuary is mostly full. An organ bangs out notes as backup for a red-robed choir. Babies gurgle from the laps of parents and big brothers seated in the pews. Ushers in white uniforms pass out individually wrapped containers of wine and packages of wafers for communion. The reverend, his tempo rising, will pause from making a key point to call on the congregation to step up their amens and hallelujahs. “Talk to me!” he shouts between breaths. The bible is waving in the air, more a visual than a reference. Midway through, Pastor Harris asks all visitors to stand up so every single member of the congregation can vacate their seats to greet them with handshakes or hugs.

There’s also business to attend to. Next week’s dance practice and chorale rehearsal will occur as scheduled. Alcoholics for Christ has changed their meeting time. Prayers are requested for a congregant recovering from illness. There are birthday celebrants to recognize and sing for.

There’s no talk of the water crisis. Not today.

Just a hymn:

“I’ve got a feeling … that everything’s gonna be alright,” they sing.

[blocktext align=”right”]“You don’t let anybody destroy your faith. No matter what it is … Because when I lose hope, and when you lose hope, we’re done.”[/blocktext]Later, I ask Rev. Harris whether it ever got hard to sing those lyrics, especially amid everything that’s happened over the last year. During the worst parts of the water crisis, did he really believe that everything would be alright?

“You don’t let anybody destroy your faith,” he says. “No matter what it is … Because when I lose hope, and when you lose hope, we’re done.”

I pose the same question to Marquese Brown, a tenth grader who attends church with his family at Saints of God. He says he knows some kids who want to stick around to drive change in the city, but many people his age want to get out.

“When they’re thinking about what they want to do in the future, they might not be ready to come back and help Flint at all,” he says. “They may just want to move out and get away from everything.”

But there are also people determined not to step away, an active community of foundations and nonprofits with an unshakable commitment to the city, and programs like the Community Education Initiative that hold real promise. Flint doesn’t need an outside savior to deliver some type of rebirth. What residents and community leaders say they need are the resources, investment, and public policy with the teeth and breadth to address big and complicated challenges.

But there are also people determined not to step away, an active community of foundations and nonprofits with an unshakable commitment to the city, and programs like the Community Education Initiative that hold real promise. Flint doesn’t need an outside savior to deliver some type of rebirth. What residents and community leaders say they need are the resources, investment, and public policy with the teeth and breadth to address big and complicated challenges.

A lot of people in Flint are already at work. Striving for better. But for a more fully restorative effort to be successful, not only in Flint, but in all the other places where poor, often minority, communities are underserved by public policy, all levels of government, and the voters who elect their leaders, must make it a priority.

Band-aids just won’t do the job.

___

Sam Gringlas is a journalist based in Michigan and Washington, D.C. He is a recent public policy graduate from the University of Michigan and the former managing news editor of The Michigan Daily.

Join us for Belt’s Happy Anyway: A Flint Anthology Launch Party on June 27, 2016 at Soggy Bottom Bar. Order Happy Anyway: A Flint Anthology here.

Belt is a reader-supported publication — become a member, renew your membership, or purchase a book from our store.