By Sarah Brumble

I arrived in Cleveland convinced the RNC would be the death of me. There is not a drop of hyperbole in this statement. And it’s true what they say: when people think they’re close to death, they do crazy things.

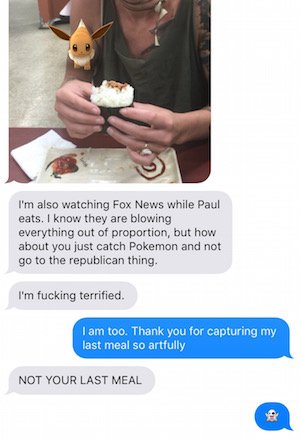

On my way out of Minneapolis, I left my affairs in order. I even went so far as to eat a last meal.

That’s also how, the morning before the RNC began, I found myself at St. Rocco’s 9 a.m. mass, on the city’s westside, and in a formerly Italian neighborhood. I’m not at all Italian; I am also not really Catholic, though sometimes I can fake it thanks to years of schooling at the hands of nuns.

That’s also how, the morning before the RNC began, I found myself at St. Rocco’s 9 a.m. mass, on the city’s westside, and in a formerly Italian neighborhood. I’m not at all Italian; I am also not really Catholic, though sometimes I can fake it thanks to years of schooling at the hands of nuns.

I really don’t know why I picked this out of all the churches in Cleveland, but after Googling Saint Rocco (a.k.a. St. Roch) everything came together. The 14th-century man was known for showing off his wounds and is invoked for protection against the plague.

Father James gave a solemn homily on the nature of communion and hospitality, and on a host’s imperative to provide for guests without “asking for anything in return.” A man in front of me took this to heart. At the end off mass, he and his family prevented me from sneaking out of the back pew.

“Are you new to the area?” Mr. Miranda asked.

Taken aback, I stammered before responding,

“Sort of? I’m in town for the week. As press. And I’m afraid I’m going to die.” I’m a terrible liar, it was very early, and I hadn’t yet had coffee.

Next thing I know, he and his wife are praying over me.

Though flattered, prayer isn’t really what I was after when I’d arrived that morning. All I’d hoped for was the respite found in churches, bolstered by the IRS’s prohibition on clergy directly endorsing candidates.

As I drove away from St. Rocco’s, which still had three more masses ahead, I wondered: what if I could get the men at the pulpits to sit down and talk big ideas with me, in secular fashion? What if I could get them to tell me about what it’s like to provide refuge in this time of geopolitical and local upheaval?

St. Rocco’s Catholic church

So over the next several days, as I navigated the circus of the RNC, I was also on a non-religious quest from God. I repeatedly asked strangers “if they knew a priest.”

It took days before I found anyone within the Catholic denomination to speak with me, and trust I wouldn’t grill them on matters of abortion, women’s rights, political endorsements, or their dorms’ appropriation by riot police.

Then a former Ford Motor Company employee, who now spends her days volunteering at a near west side church, agreed to give me a tour. She confessed looming fears that the RNC “might be really bad,” and told me her own daughter and other members of the congregation found it difficult to get to mass, given downtown’s political rats’ nest and ensuing road closures. And then she introduced me to the parish’s 84-year-old priest, who agreed to a spiritual chitchat.

Father wished to remain unnamed, not out of fear, but rather to deflect “any good that may come of this.”

I asked how his parish, which draws almost entirely from the neighborhood, had dealt with recent national and local turmoil, he told me about his own anxieties.

“I’m a little bit anxious. On the other hand you can’t let those you fear control you. We had a professor at school who said ‘Until a person experiences the absurdity of life, he or she won’t even ask the question to which religion is the possible answer.’ My field is religious education and I’m constantly giving people answers to questions which they haven’t even asked yet.”

Over the next hour, he answered my question about how one provides sanctuary in times of trouble. Sometimes he responded with food metaphors.

“Salt does not add a flavor to what it seasons,” he said. “It brings out a flavor from within. If people decide to go back to the church they grew up in, we’re being Church. They decide to be nicer? We’re being Church.”

In other cases he answered with statistics.

“You have to know God won’t write off seven-tenths of the human race. The Church was never intended to be coterminous with the human race.”

His answers calmed my nerves, but it was a private audience, and I wished others could have benefited from his counsel as well.

Old Stone Church

My next stop was the The Old Stone Church. I found the doors flung wide open. Located on the edge of the convention’s busy free speech zone in Public Square, the church caused the opinions-with-bullhorns outside to quiet and disappear. After passing a security screening, and entering the vaulted chamber, I was greeted by volunteers who explained to me their church’s thrice-fire-ravaged, Tiffany-glass-lined interior, resemblance to Noah’s Ark, and legendary history of social engagement.

Senior Pastor Rev. Dr. Mark Giuliano was happy to speak with me, and was excited that the world’s tumult was lapping at his doorstep. In fact, that the church is in the city’s epicenter is what drew him here in 2008. “I noticed that the star that marked the heart of the city was on the doorsteps of the Old Stone Church,” he said. “I thought ‘Woah. Here’s a church that’s geographically in the heart of Northeast Ohio and for almost 200 years has been the spiritual heart of Cleveland.’ So I called them up.”

Giuliano views this week’s happenings from a historic perspective.

“It’s just one of many things that happen in downtown Cleveland that we get to be a part of. I think there was thoughtful planning. I always say that those security people do what they do so that we can do what we do, which is take care of the city spiritually.”

Stained glass at Old Stone Church.

He continued, “We’re Presbyterian *technically*, and I like that.” I started laughing, but he was not upset that I found this funny: “When we’re talking faith, we’re not talking denominationalism.”

He has a prominent Canadian accent and made occasional references to Toronto, so I assumed he wouldn’t be voting. But I was wrong. “Oh, I’m a dual citizen.” He emphasized that he avoids partisanship, though, guiding the unsure to look “up, inside, and to the horizon.”

He paused, eyes twinkling, and added, “You know where I vote? Here. Old Stone is a polling station.”

I should have known that. Even if this sanctuary from politics, which I wanted to find so, so badly, ballots are cast.

Sarah Brumble is a Belt RNC Fellow and a writer and photographer hailing from Wheeling, West Virginia, and Portland, Oregon. A graduate of Macalester College’s Creative Writing and Critical Theory cult, she interned in Cambridge University Press’s West and Central Africa Branch Office before going pro and selling her work to Atlas Obscura, the American Guide, Playboy, and various other publications with mixed reputations. When not sailing through shark-infested waters or walking overland into Nigeria, she can be found hiding in the dark corners of music venues, buying very cheap plane tickets to distant lands, and not-not trespassing closer to home. She currently lives in Minneapolis.

Great article, Sarah. Thanks for visiting Cle, and our amazing church in the heart of the city. We serve our city and its people, spiritually and physically, as other OSC members have done for nearly 200 years. Love to have you come back when things are a little less “exciting.”