By Joey Horan

In the aftermath of the August 12 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in which an Ohio man drove his car into a group of counter-protesters, killing one person and injuring 19 others, white supremacists in their various forms have been making news in the Buckeye state.

In addition to Maumee, Ohio — the Toledo suburb where Charlottesville killer James Alex Fields Jr. lived — Centerville, a suburb of Dayton, garnered national attention for its connection to three men who attended the Unite the Right rally. Jacob Dix and Ryan Martin were doxxed by the popular Twitter account, @YesYoureRacist, for their participation in the torch-lit procession in Charlottesville. Shaun King, a columnist for The Intercept, identified a third Dayton area man, Daniel Borden, in a viral video that shows a group of men beating DeAndre Harris, a young black man, with clubs in a parking garage outside of a Charlottesville police station.

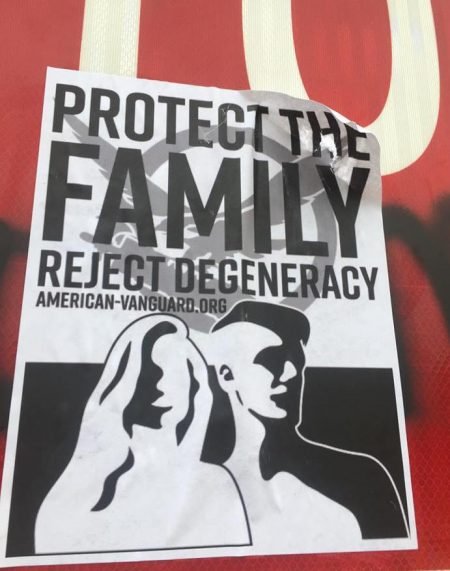

A spike in Ohio-related white supremacist activity is not limited to Ohioans who made the trip to Virginia. Within two weeks of the events in Charlottesville, recruitment flyers from the East Coast Knights of the True Invisible Empire, a group affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan, were found at Wooster College, a liberal arts school in Wayne County, Ohio. Shortly thereafter, flyers promoting white supremacist groups Identity Evropa and American Vanguard were pasted on stop signs in the progressive village of Yellow Springs, home to liberal arts school, Antioch College.

Promotional flyer of white supremacist group Identity Evropa in Yellow Springs, Ohio

In light of this increased white supremacist activity in Ohio, Belt magazine asked local law enforcement around the state how they were responding. Despite reports by activists and journalists linking the postering in Yellow Springs to the West Ohio Minutemen, a militia group known to be active in the area, Yellow Springs PD Sergeant Josh Knapp said it “could have just been anybody that was looking to get a reaction of some sort.” On whether or not he thought Yellow Springs was targeted for their progressive reputation — which includes being the first Ohio municipality to establish an anti-discrimination ordinance for gay and lesbian workers in 1979 — he replied, “I have no idea. Why is any place targeted really?”

The West Ohio Minutemen have a history of provoking the village. They were in town the night before the flyers were discovered in late August. Since the incident, members of the Traditionalist Worker Party, a white supremacist group based in Cincinnati, have also been spotted in the village.

As for a police investigation into the events, Knapp said, “We don’t know who did it, we don’t have any leads on this, there’s no follow up to it, the posters were taken down, and our case is closed.”

“There is something [police] can do. It might ultimately fail in court, but they would be showing, ‘Don’t do that shit here.’”

In Centerville, local police were more concerned with the protection of avowed white supremacists than they were in responding to any purported rise in hate activity. When asked about the three men who were doxxed for their involvement in Charlottesville, Centerville PD Community Relations Officer John Davis said: “There was such a fury to get these people, in a lot of the social media we were reading people would say, ‘We gotta get these guys,’ so any responsible law enforcement agency trying to protect the community would want to know if something like that was coming through town.”

When asked how police would respond to white supremacist demonstrations in Centerville, Officer Davis replied, “They’ve got a right to freedom of speech. As long as they’re not breaking any laws, there’s nothing that we can do about that. Really, I don’t know if there’s anything we’d want to do about that. That’s one of the fundamental rights of our country is to be able to say what you want to say as long as you’re not inciting violence.”

Short of language that contains “true threats,” said Mike Brickner, senior policy director of the ACLU of Ohio, “these groups are constitutionally entitled to distribute their literature.” Regarding police protection for such groups, Peter Moskos, an associate professor with a focus on police science at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said, “It is the job of the police to protect everyone, even sons of bitches.” But Moskos argued that shouldn’t necessarily stop law enforcement from taking action against hate groups, even when their transgressions have yet to manifest into violence. “Police have a lot of discretion, in a good way,” he said. “So to say, ‘There’s nothing we can do,’ is not true. There is something they can do. It might be ineffective, it might ultimately fail in court, it might not, but either way they would be showing, ‘Don’t do that shit here.’… At the very least, it certainly matters when leaders say things or don’t say things.”

Residents of Yellow Springs are certainly concerned about the potential for violence as rhetoric ratchets up in online forums.

Promotional flyer posted in Yellow Springs, Ohio promoting American Vanguard, a white supremacist group

“There is a fairly hefty amount of organized hate in the area, not too far under the surface,” said Mark Bateman, who lives in Yellow Springs. “I would appreciate it if the police were aware that there were tensions, that people were concerned and they kept it on their radar.”

Lindsay Burke, an activist in the Yellow Springs area, argued that local hate groups are inherently violent. “Violence is something they have already accepted as part of their platform,” she said, adding that their activity goes beyond what is protected by the first amendment. “They’re not exercising free speech, they’re exercising hate speech. The freedom of speech argument is null and void when [the group in question] historically and currently commits violence.”

The Traditionalist Worker Party (TWP), for example, is a white supremacist group based in Cincinnati, just 70 miles south of Yellow Springs. It is the political offshoot of the Traditionalist Youth Network, which was founded by Matthew Heimbach, a key organizer of the Unite the Right rally. In June 2016, at a Sacramento rally organized by the TWP, members of the party clashed with counter-protesters, resulting in multiple stabbings. Two counter-protesters suffered life-threatening injuries.

The West Ohio Minutemen are part of a network of III% militia groups tied to the Oath Keepers. They ran security at a Trump rally, in which they appeared heavily armed in military fatigues. They were also “patrolling” the streets in Cleveland at the RNC despite requests by local law enforcement to leave their guns at home.

Burke claimed that there are forces in Yellow Springs who are ready to answer white supremacist violence with violence, citing local anti-racist factions that are armed, “and they’re very vocal about it.”

At least in Wooster, citizens concerned about an increase in white supremacist activity feel confident that Wooster PD has their back. Oliver Warren, who was part of a coalition that organized an anti-hate demonstration in Wooster in response to the KKK recruitment flyers that appeared in town, said, “The police were instrumental in putting on the rally, [which was attended by some 1,000 people]. Without them, I don’t think we could have held it, at least not as smoothly.”

“They’re not exercising free speech, they’re exercising hate speech. The freedom of speech argument is null and void when [the group in question] historically and currently commits violence.”

Since the flyers were discovered, Warren, who serves as chair of Indivisible Wooster and president of the non-partisan Concerned Citizens of Wayne County, has overall been impressed with police response. “As the community grew more concerned,” he said, “they did as well.”

When reached for comment, Wooster PD Sergeant Mike Jewell said that whoever left the flyers in town “[does not] hold the core values that we have.”

Moving forward, state and local law enforcement agencies may face their biggest test yet. Richard Spencer, the white supremacist who coined the term “Alt-Right,” is currently trying to book an event at the University of Cincinnati. His request to speak at Ohio State University was rejected in early September. Spencer’s lawyer is threatening to sue any public university that rejects his request to speak for violating his client’s first amendment rights. If Spencer succeeds in booking Cincinnati, police can be sure that hate groups and anti-racist counter-demonstrators will heavily mobilize for the event.

___

Banner photo: James Alex Fields Jr. who was charged with second-degree murder for his actions in Charlottesville, Va.

Joey Horan is a writer based in Toledo, Ohio. He can be reached at [email protected].