On the little-known practice of involuntary annexation

By Nika Knight

It was a bright July day in 2013 and just like most other summer days in most other years, the tall stalks of corn, green and shining under the Indiana sun, were bending down in the breeze as a crop duster swooped low and bestowed its gifts upon them.

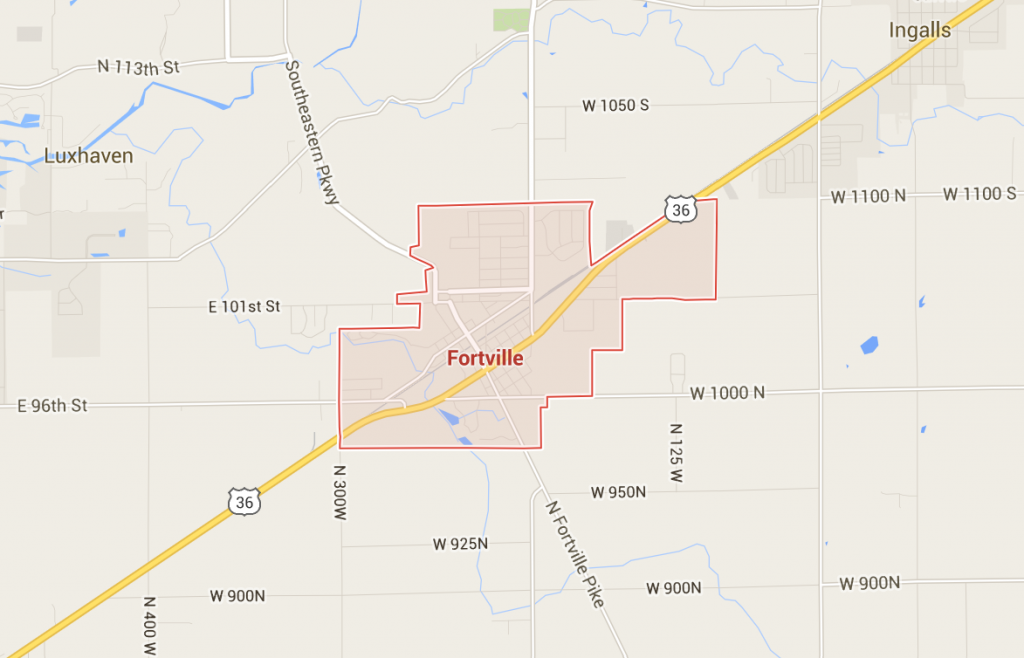

But this day was not like most other days. This was the day that the farmers who owned and tilled this land would be delivered another kind of gift. This one, unlike the crop duster’s, was wholly unwelcome: the neighboring town of Fortville sent word that it would, against the will of local landowners, move forward with an involuntary annexation of their land. This would make it vulnerable to development, taxable at the higher municipal tax rate, and someday, perhaps, no longer the sleepy stretch of quiet farmland that it had been for centuries.

This area of rural farmland — newly redubbed by Fortville as its “Western Boundary” — encompasses 644 acres and 162 residents, virtually all of whom opposed the annexation. But their opposition wouldn’t matter unless they had the time and financial resources to take legal action. The landowners would have to collect signatures from 65% of the population opposing the annexation and then reach into their pockets to supply their own legal fees to fight it in court, a process that could end up taking years and multiple appeals.

While Fortville’s annexees succeeded in raising funds and mounting their legal opposition, known as a remonstrance, the fight against the annexation continues to this day. Fortville successfully appealed a 2014 decision in the remonstrators’ favor, and in response to this summer’s subsequent decision in the town’s favor, the remonstrators asked that the case be transferred to the Indiana Supreme Court — and the court agreed to accept it. Oral arguments are set to take place on November 25th, and a decision should be handed down this winter. Nearly three years after Fortville’s first attempt to annex the land to the west of its current borders, and after hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on legal fees, the state will decide whether this annexation may proceed.This is the process known as forcible, or involuntary annexation. Indiana and Idaho are the last two states in the union to still allow the deeply unpopular practice. In Indiana, a new rise in the number of involuntary annexations has forced the state’s courts to contend with the ramifications of a long disused, newly popular, old-fashioned law.

The towns of Brownsburg, Whitestown, and Fortville are all involved in long legal fights following their efforts to forcibly annex land on the other side of their borders. (The Indiana Farm Bureau offers a closer look at recent involuntary annexations here.) It’s possible, of course, that other areas may have opposed being forcibly annexed, but lacked the time and money required to mount a legal battle against it. There’s no way of knowing, for if no legal opposition took place, there’s no official record of any opposition at all.

It’s surprising that a state with a deep libertarian streak is also one of the last states to abolish involuntary annexation — a wholly undemocratic practice, on the face of it, and perhaps one of the most blatant examples of government interference in individual landowners’ lives and pockets. Surprising, but perhaps it also shouldn’t have been unexpected: it seems likely that it was a 2008 cap on property tax increases that led directly to the newfound popularity of the practice.

Cynthia Baker, a clinical professor of law at Indiana University McKinney School of Law, explains: “Because of that law that capped property taxes, local governments have less autonomy to raise their property taxes without having their citizens raise property taxes voluntarily.” She theorized, “Another solution is to take advantage of the [annexation] statute and increase their tax base.”

These sorts of annexations are one of the most expedient routes for cash-strapped municipalities to easily recoup some of the potential tax income lost after the property tax cap passed, without taking the politically disadvantageous step of lobbying citizens to vote to raise their own taxes.

The 2008 law capping property taxes is of a piece with the state’s longtime fondness for economic freedom. Right-wing think tank the John Locke Foundation ranks Indiana as the third “most free” state in the country, and while George Mason University’s Mercatus Center rates it 16th for “overall freedom,” it puts the state in first place when it comes to “regulatory policy.” In doing so, the Mercatus Center praises Indiana’s 2012 “right to work” legislation, its deregulation of telecom and cable corporations, and notes that its zoning laws are some of the “least strict in the nation.”

But involuntary annexation does not represent the no-tax oasis of self-determination for which libertarians and their sympathizers have been aiming. While libertarians have led the fight to “reform or eliminate” property taxes in the state, the Libertarian Party is also fervently opposed to involuntary annexation.

Involuntary annexations haven’t been so prevalent in a long time, but there was an era when forced annexation was, practically speaking, the only kind of annexation — and no one objected. That time was, of course, a long time ago.

Baker explained that in the 19th century, forcible and unilateral annexation was the most popular way for a city to expand its boundaries. It was not only the most expedient option, but anyone opposing annexation would essentially be perceived as standing against progress, as the city saw itself as a vibrant bastion of such. Cities were not only symbols of culture and industry, but they also brought needed, treated water to areas that lacked it and, eventually, electricity to country homes that would have welcomed the modernization.

Baker explained that in the 19th century, forcible and unilateral annexation was the most popular way for a city to expand its boundaries. It was not only the most expedient option, but anyone opposing annexation would essentially be perceived as standing against progress, as the city saw itself as a vibrant bastion of such. Cities were not only symbols of culture and industry, but they also brought needed, treated water to areas that lacked it and, eventually, electricity to country homes that would have welcomed the modernization.

Urbanization was seen as the way of the future, and a state’s cities were critical to its economy as well as its own self-perception. Involuntary annexation was a popular method by which Midwestern cities achieved the rapid growth that defined them in the 19th century.

The mid-20th century, though, saw the rise of the suburbs: suddenly the outskirts of the city were wealthier, populated by residents who had departed the city by choice, and annexing them became a different proposition entirely. The practice dropped out of favor, to a large extent. In the last four years, two of the four states that still allowed the practice outlawed it.

The municipalities and politicians who are in favor of Indiana’s annexation laws make similar arguments to those shining, rapidly expanding cities of the past: they also argue that involuntary annexation allows them to bring modern municipal services to rural areas, thus improving them while the cities are able to simultaneously secure their own future growth. This is of course also true for voluntary annexation — and it’s difficult, in a world less in thrall to the concept of urban growth, to frame involuntary annexation as necessarily better than its more democratic counterpart.

This hasn’t stopped anyone from trying. Susie Whybrew, a local landowner and leader in the remonstration against the Fortville annexation, told me, “Fortville changed their mind about why we should be annexed so many times.”

Initially, Whybrew said, there was talk of accomplishing the annexation before state laws were revised to limit the practice. Then the town argued that the rural landowners were using municipal roads without paying for them. Whybrew countered, “I think that is the most ridiculous claim I ever heard. There are so many other people in the area that drive through this town. There is a state highway that goes through here!”

The town also claimed that Whybrew and her neighbors were using a Fortville park. “They assumed that,” Whybrew says. “There was no evidence for it … most kids out here play in their backyards.” No one from the town had surveyed residents, she says, to find out if they did, in fact, use the park. (I emailed Fortville’s town manager to ask about this, but didn’t receive a response by press time.)

Finally, the town argued that some residents of the annexation zone use their water supply. But the town itself ran a water line to the local school back in 2007, offering residents the chance to hook up to the line. A few people took them up on the offer, and despite the fact that it’s only a small number of the local population, Fortville now claims it is supplying water to the zone.

[blocktext align=”right”]It’s surprising that a state with a deep libertarian streak is also one of the last states to abolish involuntary annexation…Surprising, but perhaps it also shouldn’t have been unexpected.[/blocktext]The reasons Fortville continues to pursue the annexation make little sense, as it has now cost the town much more money than they are likely to recoup in tax income anytime soon.

Whybrew has another theory. “There is a wellhead that extends down slightly into this area, slightly,” she said, “and I think they want to tap into that wellhead.” Fortville, she told me, owns a water treatment facility and it is making money by selling water to a nearby county as well as a rapidly growing development just north of it.

Whybrew speculated that the town may be concerned that another private developer or municipality will come in and start selling water to those living in the Western Boundary. “No one has expressed interest in developing out there,” Whybrew says. “There’s no threat from any other water companies. What it boils down to is water and tax money.”

In court, the town has repeatedly made the argument that it will supply — will be required, by law, to supply — municipal services. Locals, however, argue that they have no need for additional services (and, furthermore, that the town never asked if they wanted them in the first place). They feel adequately protected by the county’s police and fire department, and note that municipal trash collection services aren’t equipped to handle the kind of waste produced by commercial farms. They are content with wells and septic tanks, and some worry about the quality of the town’s water.

And the last argument Fortville has advanced is perhaps the most baffling: it claims it needs to “square its borders,” arguing that police have gotten lost on the roads with boundary lines that don’t make a perfect square. Whybrew characterized this argument as “laughable,” and pointed out that the town created its irregularly shaped borders with its last annexation (a voluntary one), in 2007. As for police having trouble finding their way? There’s only one road that leads to the area.

Whybrew’s advocacy against forcible annexation has already been successful, in a larger sense. The state legislature radically rewrote the state’s annexation statute this past year, in response to lobbying from Whybrew and other dissatisfied annexees, and made it easier to oppose an involuntary annexation: Now, only 51% of landowners need sign a petition in order to trigger a remonstrance, which in turn sends the case to the courts. If 65% of landowners sign a petition against it, the annexation can’t proceed at all.

Whybrew’s advocacy against forcible annexation has already been successful, in a larger sense. The state legislature radically rewrote the state’s annexation statute this past year, in response to lobbying from Whybrew and other dissatisfied annexees, and made it easier to oppose an involuntary annexation: Now, only 51% of landowners need sign a petition in order to trigger a remonstrance, which in turn sends the case to the courts. If 65% of landowners sign a petition against it, the annexation can’t proceed at all.

This new law makes it much easier to oppose the forcible annexations, but it doesn’t eradicate the practice entirely. Still, it indicates that these kind of annexations may finally, if slowly, be disappearing from the state of Indiana.

Looking into the financial side of these legal fights, one imagines the towns themselves might not mourn the disappearance of the controversial practice. While many of these annexations were perhaps intended to increase a town’s funds, they have led to court battles that have ended up draining the coffers of many of these cash-strapped towns.

Whybrew filed a Freedom of Information Act request last year to try to learn how much the town had spent on fighting the annexation battle, after the town appealed a court decision in October 2014 that was not in its favor. The total shocked her: the town had spent over $200,000 on legal fees up to that point. (And it’s certainly gone on to spend more in the year since, she points out.)

Whybrews’ and her neighbors’ legal fees have also not been insubstantial, particularly considering the fact that many are retirees and living on a fixed income. They were able to raise $50,000 for the legal battle, $15,000 of which remains for the latest appeal. Not to mention the time required to fight the good fight: Whybrew, who is retired, says the court battle has become a kind of full-time, unpaid job.

[blocktext align=”right”]“At one of the early meetings in 2013 with the town council a resident said she would not do business in Fortville anymore, not even with the funeral home when she died.”[/blocktext]And there are also the emotional costs. Whybrew told me, “The way they did it was a really bad thing. They did not come out and speak to people about this. We had no idea that they were considering it. We considered it an ambush, a land grab. And they have pretty much refused to speak with us, from the beginning.” Whybrew and her neighbors attempted to have meetings with the town council, but the councilmembers refused to come out to the area. “It always had to be on the their turf,” she said. (The town didn’t respond to my request for comment.)

While the town talks about building a community, Whybrew continues, “they pretty much burned the bridges out here. There is a lot of resentment that has come out of it.

Since the town’s first letter notifying residents of the annexation in the spring of 2013, Whybrew says, “There has been a big surge of people making a point not to go into town anymore, and not to patronize the few businesses that are there.” In an email, she expanded on the depth and extent of the residents’ anger toward the town: “At one of the early meetings in 2013 with the town council,” she wrote, “a resident said she would not do business in Fortville anymore, not even with the funeral home when she died.”

I wrote to the town manager and asked if Fortville has seen an economic impact from the informal boycott, but he didn’t respond. Whybrew herself does wish that residents’ refusal to go into town didn’t mean hurting small, local businesses, but when it comes down to it, “They elected those town council members, and we didn’t. If it’s hurting their businesses, they need to go to the town council.”

The annexation feels like a deep violation of the local sense of community and neighborliness, and it’s obvious when speaking with her that Whybrew holds these values very dear. “The sad part is, it’s not been very friendly,” she told me. “It just really wasn’t. How would you feel if someone delivered a letter to you, and told you that this dictatorial action was going to happen?”

She lamented, “That’s not welcoming, and it’s not friendly.”

___

Nika Knight is a writer and translator. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Grist, and The Rumpus, among other places.

Don’t miss a thing in the world of Belt by signing up for our weekly newsletter: http://bit.ly/1Qto86t

![Credit: Scott Morris [https://flickr.com/photos/scottmphotos]](https://beltmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fortville-tracks-s.jpg)

Very good and truthful article. Like Indianapolis, towns should be working on condensed business, homes and other living quarters. That’s what people want and it’s what’s admired of Indianapolis by the entire country. people love to come to Indianapolis because everything is within walking distance. Why would towns, like Fortville, want to annex property that helps them spread out rather than condense.

If you were to spend just one night in town, you’d figure it out. On average, 5 trains a night go through, whistles sounding at all 5 street crossings and the track noise keeps even those of us two miles away from getting a good nights sleep. Development around here is going to be very risky.