By Karen Halvorsen Schreck

In her debut novel Swarm Theory, Chicago writer Christine Rice reimagines a landscape from her past, a mash-up of disintegrating farmland and emerging suburb that most Midwesterners will instantly recognize — one of those disorienting, off-kilter places that, for lack of a better word, we call a town. Rice calls the fictional place New Canaan, Michigan, and the city just over that way is Flint. Like the setting, the narrative spans the awkward ending of one thing — the 1970s — and the confused beginning of the following decade. The people in this place, too, seem to be frequently in transition — or they’d like to be, want to be, need to be anywhere but here, where the stays of commerce, industry, and agriculture have come undone.

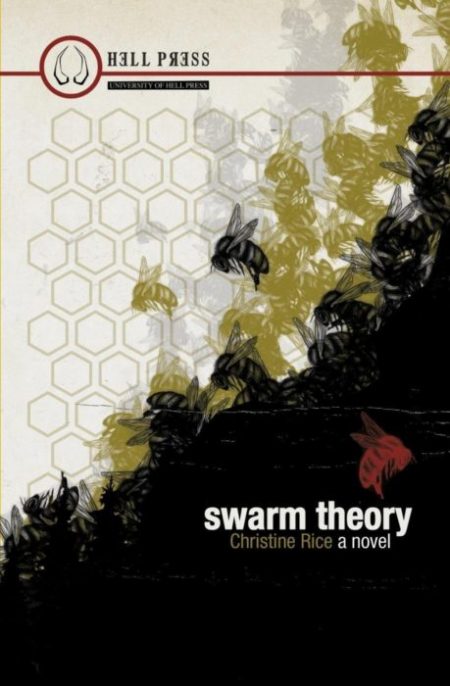

What Rice reveals, though, is that the middle of nowhere is never simply that. With passionate intensity and precision, she maps the desires and frustrations of impeccably drawn characters whose lives inevitably collide and connect, repel and reconcile. Published this past April by Oregon-based University of Hell Press, Swarm Theory, though historical, is chillingly contemporary in its implications. The form of the novel, which is intricately constructed from connected short stories holding shifting points of view, only highlights the fact that in a place like this, everyone knows everyone, for better and worse.

![Courtesy of christinemaulrice.com [credit: David Rice]](https://beltmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/1439913999539-450x451.jpg)

Courtesy of christinemaulrice.com [credit: David Rice]

* * *

BELT: You chose to introduce Swarm Theory with an epigraph pulled from the Tennessee Williams play Camino Real: “Caged birds accept each other but flight is what they long for.” Could we start our conversation by talking about this quote — about the central cage/hive in your book, the community that is your fictional town, New Canaan, Michigan, and the way that place works, for good and ill, on the individual characters who live within its limits? Like a setting in a play by Tennessee Williams, New Canaan isn’t just Anywhere, America. In what ways does this suburb, located somewhere between Flint and Detroit, play an important role — perhaps the most important role — in Swarm Theory?

Christine Rice: Tennessee Williams is one of my favorite writers and I’ve had a long-running love affair with his Collected Stories. Many of those stories are so flawed and others, to me at least, are so imperfectly perfect. All of them are heartbreaking. Unlike the majority of his plays, his short fiction is not super polished and so they feel risky. They feel like Tennessee Williams off balance (which draws and fascinates me).

Anyway, the place, Camino Real, is an inescapable end. “Caged birds accept each other but flight is what they long for,” is Marguerite’s line. She’s trapped by love and landscape. I’d read the script of Camino Real many, many years ago and loved its dreamlike nonlinear narrative, its experimental nature. I guess it worked a number on my subconscious.

The first story I wrote (and I say story because I didn’t know until about half-way through that the narrative was shaping into a novel) was “The Art of Survival.” The character that revealed herself to me felt trapped by her overbearing boyfriend and the small town where they lived. She felt like she was on the verge of becoming something else, something aside from the place where she’d been born, and something completely different than the way that place (and her family history) defined her. She felt like, if she didn’t get the hell out of New Canaan, she would eventually be limited by and to that place.

So, to answer your question, New Canaan became this floating nowhere between two dying cities. It was very much impacted by the economic ups and downs of General Motors (as everything in Michigan is) and, in the 1980s, it was also hanging in this weird small-town-to-suburb limbo.

My characters don’t influence place as much as they are defined by it. They emerge out of place. New Canaan is based on my hometown of Grand Blanc (a suburb of Flint) but, in the end, New Canaan and Grand Blanc are very different. I began the stories in a place very similar to Grand Blanc but then realized that I needed to create a new town, a new place, separate from the place I knew, because the facts kept getting in the way of the narrative. I didn’t want people to read it and say, The church isn’t there. Or, The high school is east – not west – of the train tracks. Or, Nothing like that happened here. I kept getting tripped up by those details. So I finally said, ‘Screw it,’ and imagined New Canaan.

BELT: Since we’re talking place, I’d love to know more about your connection to Flint, Michigan. Thanks in part to Michael Moore’s Roger & Me and the current water crisis, the city can be seen as representative of a certain kind of systematic failure — but then there are the citizens of Flint who challenge stereotypes left and right. One of the many things I love about Swarm Theory is that Flint always felt there to me, hovering just over the horizon, a presence that evoked assumptions on my part. But because the characters in your book were anything but clichéd, because your characterization, in fact, challenged assumptions about Flint and its surroundings, I was confronted by own lack of understanding. Was this intentional on your part?

Rice: That’s a very lovely way to put it…like Flint was “hovering just over the horizon.”

I’m a big fan of Michael Moore. At the same time, as you can probably imagine, because Michael Moore established the conflict around the devastating effects of General Motors plant closures, many people felt betrayed by his less-than-favorable portrayal of Flint.

But establishing Flint as a great place wasn’t the film’s focus. Had he established Flint as a great place to live AND presented the devastation brought on by plant closures, that film might have been 18 hours long. He’s a master storyteller and knows how to shape a narrative.

After the huge popularity of that film, I distinctly remember that, when people asked me about it, I would simultaneously defend Roger & Me and Flint. Roger & Me still evokes complex emotions for me.

[blocktext align=”right”]I did not intentionally set out to challenge assumptions about Flint. I simply set out to write the stories — and characters — authentic to my experience.[/blocktext]My family and I owe everything to Flint. Both sets of my grandparents were immigrants. On my Volga German side, my grandfather worked on the line to support his 12 children. On my Lebanese side, my mother and her seven brothers and sisters first worked at Hamady Brothers and, eventually, opened their own grocery stores. Directly or indirectly, General Motors made all of that possible.

As a child growing up in the late 1960s and 1970s, I always found Flint magical. It had a vibrant downtown (and is currently undergoing a renaissance). There was (and still is) the Flint Public Library, the Flint Institute of Arts, the Flint Farmer’s Market, Whiting Auditorium, and other cultural attractions. Back in the day there were amazing clothing stores like The Vogue and The Fair and Smith-Bridgman. There was also Capitol Theater.

The late 1970s and 1980s — as General Motors started pulling out of Flint and when urban sprawl started luring businesses out of downtown — was a confusing time. The quality of GM cars had suffered from years of internal strife, competition was suddenly fierce, and things just couldn’t continue the same way they had. Flint was, essentially, a one-industry town. And that industry was pulling out of Flint.

As depicted in Roger & Me, there were, of course, the haves and the have nots. Most distinctly, though, Billy Durant’s vision and, eventually, the United Auto Workers in concert with General Motors, made it possible for a rock-solid middle class to survive. Once Billy Durant had been forced out of GM, and General Motors and the UAW stopped listening to each other, things started to get ugly. Fault didn’t lie on just one side; a symbiotic relationship had gone awry.

I did not intentionally set out to challenge assumptions about Flint. I simply set out to write the stories — and characters — authentic to my experience. And, overall, the characters and events in Swarm Theory emerged from bits and pieces of people and things I knew or had heard about. No one character is based solely on one real person. They are very much composite characters.

This latest crisis in Flint — it is hard to even get my head around it. It’s just infuriating. It’s criminal. It’s all those things but it is such a tragedy on a human level that it just…I don’t even know…there are so many issues that just flummox and sadden me about this water crisis. It seems overwhelming and I’m just reading about it, not living it.

BELT: Tell us about shaping a novel out of connected short stories. I love the form, but I can think of few examples that are as successful as yours. (Love Medicine and Olive Kittredge come immediately to mind.) Could you talk about how the book came to be for you? How did you keep the stories so balanced in their intensity and focus?

Rice: Love Medicine is one of my favorite novels. I’ve read everything by Louise Erdrich (except LaRose). I would be content to have one millionth of Louise Erdrich’s or Elizabeth Strout’s talent..but thank you for that.

The form of this book came organically for me. After I wrote “The Art of Survival,” I wrote “Swarm Theory.” And then I realized that this town, this area, had so many stories. As far as intensity and focus, I just kept taking one story at a time. I didn’t worry about chronological order. In fact, I didn’t even think about chronological order until an agent asked me to put the chapters in chronological order — which I did — and tried to write bridge chapters. As you can imagine, it really took the punch out of the overall narrative.

In the meantime, University of Hell Press managing editor Eve Connell accepted the original version and asked me for an updated version. I sent her the chronologically ordered manuscript and she said something to the effect of, “What happened to your book?! Put it back the way it was!” She felt strongly that readers were smart enough to put the pieces together. And of course she was right. Then U of Hell founder Greg Gerding worked out additional bugs in the narrative with me and said, “Chris, this is a novel, not linked stories.”

I couldn’t have asked for a more attentive publisher and editor. I feel incredibly fortunate to have found them and to have worked with two writers (who also happen to publish books) on Swarm Theory.

BELT: You expertly shift point of view within a story; within a paragraph, and sometimes even with a sentence. Is this your typical MO — this kind of fluid consciousness? And if it’s particularly important to this book, why? Also, I’m curious to hear more about why you divided the book as you did, into the four sections labeled “Plot Point One, Plot Point Two,” etc.

[blocktext align=”right”]This book would not exist without multiple points of view, the multiple voices in my head.[/blocktext]Rice: This book would not exist without multiple points of view, the multiple voices in my head. In a way, Swarm Theory is New Canaan’s story. And that meant I was obliged to give space to multiple characters’ stories. There was no other way.

For this book, I never thought about plot points. This is a blessing and a curse. This is, probably, why certain agents had a tough time getting behind my work. They would say something like, ‘I love the writing but…’ It’s that but that always killed it for me.

The separate sections came after I wrote that last chapter. I took every single chapter — printed — and laid them out the length of the house, from front to back. That’s when I started putting them in story order. Not chronological order.

The stories in each section seemed to fit together…somehow. And the scientific method helped me organize those sections. So, I guess, to revise my earlier answer, maybe Plot Point One and Plot Point Two rattled dully in my head after I’d written about 200 pages of the book, once I started assembling the different sections, once they started to coalesce around certain characters and events.

BELT: I kept thinking of Flannery O’Conner as I read the last sentences of your stories, which consistently end not with a whimper but a bang. For me, this added to the momentum of the book. Though the stories could stand alone, and indeed have in various journals and magazines, at the conclusion of each, I felt a real urgency to turn the page and start the next. There’s something about the push and pull between stories, and how this keeps the book moving at the pace it does, even as there are shifts in time and place and point of view.

Rice: Endings are so hard for me to explain. There can be only one right ending, yes? But that’s interesting, that concept of the ”push and pull” and pacing. I’m glad that the endings made you want to start reading a new story.

I’m not sure if I can add much to that thought except to say that it’s something I know I’ve hit when I hit it. Endings that make my head spin, because of the possibilities they suggest, are my favorite endings.

BELT: Tell us a bit about the history of Hypertext Magazine, where it is now, and what you’re imagining for the future.

I had been editing an annual print literary journal at Columbia College Chicago for a few years and loved that process so I started looking into what it might take to start an online lit mag. I originally envisioned Hypertext Magazine as a one-stop arts mag with music, visual arts, literature, and food reviews and coverage. I soon realized that was unrealistic with no budget. So we focused on fiction and creative nonfiction.

I also wanted to help promote independent authors and presses.

From a humble beginning, we now get 8,000-10,000 visitors each month. And those visitors view, on average, 3-4 pages. And that’s all organic traffic. We’ve paid for no advertising.

My next job is to establish Hypertext Magazine and Hypertext Studio as 501c3 organizations so that we can start paying writers.

BELT: A bit about publishing: could you talk about the proverbial state of things — mainstream vs. indie vs. self — and how you negotiate these different venues?

BELT: A bit about publishing: could you talk about the proverbial state of things — mainstream vs. indie vs. self — and how you negotiate these different venues?

Rice: We’re on the verge of a golden age of publishing. There needs to be more diversity in the publishing industry and we’re at a tipping point where the indie presses will weigh in hard and keep leading the way. The accessibility and affordability of on-demand publishing has really been a boon to independent publishers. That fact alone will bring more diversity to readers who long to read about characters with whom they share a kinship, with whom they can identify.

And even though there is a lot of dumb on the internet, there are also incredibly democratic and intelligent and thoughtful spaces and sites.

So many young writers (and not-so-young writers) have an entrepreneurial spirit. They’re not waiting around for the gatekeepers to give them the go-ahead. I wish I’d been more like that when I was younger. It took me a really long time to learn my craft. I’m not ashamed of that — I’ve always been a late bloomer. But sometimes I wish I’d started my own magazine sooner.

The writers and publishers I admire spur me to take risks on the page and in publishing. There are so many entrepreneurs across the globe producing zines, writing and illustrating graphic novels and comics, managing their own lit sites. I could be reading 24/7, 365 days a year and not even make a dent in what’s available.

I’m also incredibly inspired by Midwest writers. There is so much magnificently vibrant and lyrical writing coming out of the Midwest right now. It’s a good time to be here, to be in this community, to be a Midwest literary citizen.

___

Christine Rice will sign copies of Swarm Theory from 2-6 pm Sunday, June 12, at the Chicago Writers Association tent at the Printers Row Lit Fest. She reads from the book Sunday, June 26, at 7 pm at Sunday Salon Chicago, Riverview Tavern, 1958 Roscoe in Chicago.

Karen Halvorsen Schreck is the author of the historical novels Broken Ground (Simon & Schuster May 2016) and Sing For Me, along with two young adult novels, a book for children, and various short stories and articles. The recipient of a Pushcart Prize and an Illinois State Arts Council Grant, she received her doctorate in English and Creative Writing from the University of Illinois at Chicago. She lives with her husband and their two children in Wheaton, Illinois

Belt is a reader-supported publication — become a member, renew your membership, or purchase a book from our store.