By Lisa Holewa

It is Small Business Saturday, and South Milwaukee’s downtown looks ready: holiday lights are strung from light posts on either side of the charming brick street, lined with storefronts dating back to the 1920s.

There are just two problems.

First, no shoppers. A bulky woman bundled in a parka and hat hurries two small dogs down Milwaukee Ave. She is alone, and she is not shopping.

Second, many of the shops are closed this brisk afternoon, closed for the day or closed down completely. A couple walks to a game shop, tries the doors, finds them locked, glances up and down the empty street and heads back to their car.

Like many cities in the U.S., particularly in the Rust Belt, South Milwaukee was defined by manufacturing. Now it’s facing decisions that will inevitably change an identity dating back to 1893.

At the other end of Milwaukee Ave., Mari’s Flowers is open for business — warm and welcoming (albeit currently without customers). Owner Mari Cucunato has hot apple cider and homemade brownies. She is ready for that evening’s Gallery Night, which will keep a dozen or so downtown merchants open until 9 p.m, hosting local artists and bringing a bit of holiday spirit to the shops.

“But where are all the store owners now?” she asks in frustration. “Why is everyone closed?”

This morning, Cucunato says, she made the rounds to businesses participating in Gallery Night to share the freshly-printed brochures mapping the locations.

“But no one was open!” she exclaims. “Why? Because they were going to have to be there late for Gallery Night, so they just closed down for the afternoon.

“Who does that?” she asks.

Cucunato is new here. She doesn’t understand.

* * *

South Milwaukee is, not surprisingly, a city south of Milwaukee, about 10 miles from downtown. Just five square miles in size and with roughly 21,000 residents, South Milwaukee sits along the shores of Lake Michigan, east of the interstate linking Milwaukee to Chicago.

It is also a city at a crossroads.

Like many cities in the U.S., particularly in the Rust Belt, South Milwaukee grew up around manufacturing, was defined by manufacturing. And now, it’s facing decisions that will inevitably change an identity dating back to 1893, when the excavating equipment manufacturer, Bucyrus, moved its headquarters here from Bucyrus, Ohio, just one year after South Milwaukee was granted its village charter.

Most of the steam shovels used to create the Panama Canal in the early 1900s were made by Bucyrus in South Milwaukee.

More than a century later, In 2010, Bucyrus announced it was being sold for $8.6 billion to Caterpillar, which at the time promised to maintain a significant presence in South Milwaukee, but over the ensuing years, Caterpillar moved the bulk of its South Milwaukee operations elsewhere, and, in 2017, announced that hundreds of the remaining technology and management jobs in South Milwaukee were being relocated to Arizona.

Now, South Milwaukee is looking at 1 million square feet of empty space in its small downtown.

“It’s tragic. It’s disappointing. You can’t help but be a bit sad,” says South Milwaukee Mayor Erik Brooks, who has scrambled to hire the city’s first economic development director to deal with all that empty space.

“But it’s not going to define us. What happens next, what we do now, that is what will define us.”

The truth is, though, that South Milwaukee is one of those cities that always has been defined by its industry. Wisconsin historian John Gurda calls it “geographic determinism.” “Industry has been in South Milwaukee’s DNA from the very start,” he says.

Bucyrus may not sound like much, if you’re not from here. It’s difficult to pronounce (boo-SIGH-rus). It’s not a household name, unlike say Caterpillar (whose familiar black and yellow logo figures into South Milwaukee’s new challenges). But Bucyrus and South Milwaukee have history, and have made history together. It was in South Milwaukee that Bucyrus made the steam shovels used to dig the Chicago Drainage Canal. Here, it manufactured the equipment used to mine California gold fields, to shovel the Mosabi Iron Ranges, to expand the New York State Barge Canal. Most of the steam shovels used to create the Panama Canal in the early 1900s were made by Bucyrus in South Milwaukee. A famous 1906 photograph shows President Theodore Roosevelt operating a Bucyrus steam shovel, digging the canal. By 1925, Bucyrus became the largest manufacturer of excavating equipment in the world, and it once employed 10 percent of the population of South Milwaukee.

Teddy Roosevelt on a Bucyrus machine at the digging of the Panama Canal in 1906.

The machines made by Bucyrus are so huge they’re hard to imagine, if you’re not familiar with mining equipment. Think skyscraper-big, at least in the early days of skyscrapers. An 11-story blasthole drill that briefly became famous for neatly blasting a huge hole to rescue two coal miners trapped in a Pennsylvania mine. Or the Big Muskie, still the biggest mobile earth-moving machine ever made at 22 stories high and with a bucket as large as a 12-car garage.

“It was not quite Harley-Davidson,” says Gurda, the historian. “But Bucyrus did some sexy stuff. It was a very strong brand. There was a reflected glory in South Milwaukee because of it.”

When Caterpillar bought the company, Gurda notes: “It was a painful break.”

“I wouldn’t go so far as to say it was ‘ripping the heart out’ of the city,” he says. “But it was in that ballpark.”

* * *

While the United States lost 5.7 million manufacturing jobs in the 2000s, things felt different in South Milwaukee. Bucyrus was bustling. The company started 2000 with $289 million in annual sales of its specialized mining machines. By 2010, when Bucyrus announced the Caterpillar deal, it was selling $3.65 billion annually.

In some ways, then, the city became a victim of Bucyrus’s success. What would the sale to Caterpillar mean for South Milwaukee?

A story in The New York Times about the deal noted that Caterpillar “would locate the headquarters of its mining business in South Milwaukee, Wis., where Bucyrus is based, and that it would preserve the Bucyrus brand.”

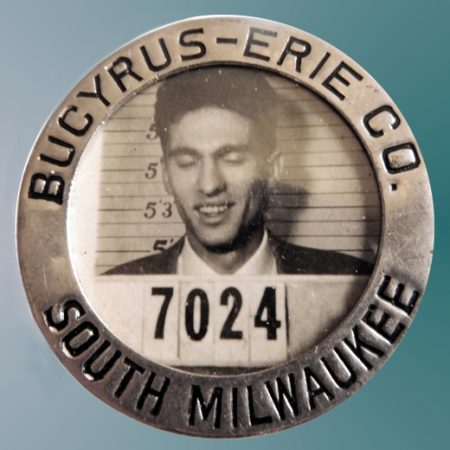

An old employee badge.

Or, as outgoing Bucyrus CEO Tim Sullivan told The Milwaukee Business Journal: “The Bucyrus name will remain intact at the sprawling South Milwaukee manufacturing complex where mining equipment such as shovels, drills and draglines are produced.”

The city, worried about the change, breathed a sigh of relief.

Until the day the sale was finalized in the summer of 2011. Within hours, the familiar Bucyrus signs hanging in South Milwaukee came down. Black and yellow Caterpillar signs went up.

“I returned from a couple days of fishing on Sunday, and the first thing I saw is the sign on Milwaukee Avenue had already changed,” Mayor Brooks, then a city alderman, wrote on his blog at the time. “And all the other building signage saying Bucyrus had also been taken down. Even the Bucyrus website was gone. Just like that.

“Just like that, the name that was such a critical part of South Milwaukee history for 118 years had disappeared — vanished like it had never existed. Here on Thursday. Gone on Friday.

Welcome, Caterpillar. Good-bye, Bucyrus,” Brooks wrote.

Caterpillar’s mining equipment manager, Steve Wunning, had a different take on the decision.

“We call this day one. It’s a historic day,” he said. “Bucyrus is a great name in the industry. It’s absolutely legendary. But Caterpillar has a good name as well.”

* * *

Eighteen months after the sale was finalized, as union contract negotiations were about to begin, Caterpillar announced it was laying off 300 workers at the South Milwaukee plant. This represented about 40 percent of its union production workers in the city.

Also in 2013, the city and its schools were ordered to pay Caterpillar back more than $1.2 million in property taxes when the state sided with Caterpillar after a lengthy dispute, agreeing the mining company had been overcharged over the past five years. Though the tax challenge started with Bucyrus, the money was being paid to Caterpillar, and it stung. The last payment was made in 2017.

Oddly, however, a small display at the South Milwaukee Public Library may best illustrate the underlying tension between the city and its biggest resident. Housed in the glass display case at the library’s entrance, tiny models of cranes sit before historical photographs of mining equipment. The display traces some of the history of Bucyrus in South Milwaukee, and it is a small segment of the artifacts once on display across the street, at the Bucyrus Heritage Museum.

While the United States lost 5.7 million manufacturing jobs in the 2000s, things felt different in South Milwaukee. Bucyrus was bustling.

The Heritage Museum opened in 2009 on one floor of an empty industrial building at Bucyrus. After the sale to Caterpillar, a project to expand and upgrade the museum was fast-tracked; word was that the museum upgrades were part of the deal. It quickly re-opened as a gorgeous three-story museum and library with two floors of prototypes and displays including scale models of those Panama Canal shovels, life-size replicas of machine parts, a 50-seat theater, interactive exhibits and a gift shop.

Hopes were, that by working with Milwaukee tourism groups, busloads of visitors from the Harley-Davidson Museum there might visit, staying to have lunch at a South Milwaukee restaurant or to catch a show at the Performing Arts Center.

“Think of the potential economic impact that brings to our city,” Brooks wrote at the time. “Well, this is not just a fantasy. This may be reality sooner rather than later thanks to this major investment in a truly unique community attraction.”

But the museum closed almost as quickly as it had re-opened. Now, it’s this tiny display at the library.

There is a GoFundMe page by a local group that recovered the artifacts. They’re aiming to raise $10,000 to catalog and store them. In addition to fundraising, the page used to contain what was perhaps the most public display of any sort of anger directed at Caterpillar by city residents, including the most simple of comments: “F Caterpillar.”

When offered a chance to comment on the museum closure, the group responded via email: “Currently, we have no interest in making any public comments regarding Bucyrus or Caterpillar, as it has nothing to do with our efforts to display the artifacts of industrial history in South Milwaukee.”

Soon after, the negative comments disappeared from the page.

* * *

South Milwaukee has a lot of things going for it: that small-town feel, a historic post office, inexpensive housing, not to mention a century-old, 380-acre county park with bluffs overlooking Lake Michigan and a secluded rocky beach along its shores.

The city’s motto, posted on signs at both ends of the city, is “Proud Past, Promising Future.” It is a place where families live for generations.

A comprehensive report written for the city in 2016 puts it in technical terms. “The long-term continuity of family generations in South Milwaukee seemed exceptionally high. Many public participants reported that they grew up in South Milwaukee, moved back, and still had many family ties to parents, siblings, and friends and others living within the community. This type of social cohesion is not typical of many urban neighborhoods and inner ring metropolitan communities.”

Put more personally: at South Milwaukee High School, one of the football players plays on a field named for his grandfather, who used to coach the team. And the former coach’s granddaughter may perhaps some day break the high school track record set back in 1979, by her aunt. These sorts of connections are common here.

“Just like that, the name that was such a critical part of South Milwaukee history for 118 years had disappeared.”

Mayor Brooks is more or less considered a newcomer, having lived in the city for about 15 years. Like many new residents of South Milwaukee, he purchased his house from its original owners, who had built it and raised their family there.

“It’s a story that’s told over and over again, on every street,” he says.

Demographically, South Milwaukee is now changing. Census data shows that it was made up of 95 percent white residents in 2000. By 2015, it was 85 percent white, with the Hispanic population growing the most quickly (to 8 percent).

Again, that’s the picture in the most technical terms.

You could, perhaps more tellingly, look at the city’s churches to see the roots and changes. For many years, South Milwaukee had four Roman Catholic churches. They merged about a dozen years ago into one parish, with the church site at one location and the school at another.

The other two buildings? One is now the Milwaukee Chin Baptist Church, a congregation made up mostly of Burmese refugees. The other, after sitting vacant for five years, now houses Masjid Al-Huda, a Muslim congregation that operates a mosque at the site.

Mayor Brooks is proud of the mosque and its acceptance among South Milwaukee residents. He tells the story of being confronted by an angry man at a Fourth of July parade after the mosque was established.

“He said: ‘Hundreds of us were opposed to that mosque!’” Brooks recounts. “And I sort of smiled and continued on my way. And later I thought to myself: Yes, hundreds probably were opposed. But that leaves about 20,000 of us who welcomed it.”

* * *

The marquee over the Garden Theater, which is now a board game store.

A movie made about South Milwaukee in the 1930s shows people streaming from the city’s Garden Movie Theater, hats on men’s heads, women all in skirts, children neatly dressed, smiling and waving.

Today, that theater marquee still stands. It reads: Board Game Barrister, and no, that’s not the name of a movie.

It is a local retail chain owned by Gordon Lugauer, who has quickly stopped in at the South Milwaukee warehouse on the busiest shopping weekend of the year, as he makes his way among his other retail locations.

Board Game Barrister is a board game shop with three other locations in the Milwaukee area, two in thriving shopping malls and one along a retail corridor near a shopping mall. Those locations keep regular hours, of course. Games are displayed for people to touch, hold and examine. There are tables for people to play games, hold tournaments.

The South Milwaukee location, however, is not at all like the others. Among other things, it has irregular hours, and no board game tournaments. But that’s South Milwaukee, explains Lugauer.

Lugauer’s family moved their carpet business, South Milwaukee Carpet and Vinyl, to the building when he was about three or four years old, in 1976. The family lived above the store. Next door, the once-thriving Garden Theater was by then operating as an arcade. One of the arcade games sparked a fire that destroyed the inside of the building. And so, the Lugauer’s carpet store took over the space, connecting the buildings and opening the former theater side as a warehouse.

Upstairs, the projection room of the theater became Lugauer’s bedroom, right behind the marquee. He and his brother played and invented board games together in that space above the family carpet store.

“That’s the romantic version,” Lugauer says, laughing. The other part of the story is that times were hard.

The downtown that once had grocery stores and five-and-dimes and that movie theater now had just a handful of specialty stores. But in the late 1970s into the 1980s, that didn’t really seem to matter. Average middle class Midwestern families had cars and big box stores were only getting bigger. Who shopped local?

“The people in South Milwaukee stopped supporting local businesses 40 years ago,” Lugauer says. “An entire generation or more has grown up without shopping here. And that hasn’t changed.”

Lugauer’s father retired in 2014. At the time, he brought a friend, a commercial real estate agent, to the building. The friend looked around at the joined buildings, the additions, the alterations that spanned more than 100 years and a devastating fire. He said he couldn’t take the listing.

“And so I did what a good son would do so my parents could retire,” Lugauer says. He bought the building. And then he faced downtown South Milwaukee.

“I looked up and down the street and said: ‘What quality of tenant am I likely to be renting to? Oh man.’ And that’s how I became the tenant.”

Today, the former theater section serves as Board Game Barrister’s warehouse. The original carpet store serves as a small retail space displaying shelves of games rejected from the other stores, all at clearance prices.

“This is a masonry block shell with a roof,” he says. “I may want to do ‘x’ here, but the reality is different. And we have buildings like this all up and down Milwaukee Avenue.”

Lugauer does his best to keep reasonably regular hours. But this store is not where he earns his money. Instead, he says, its existence is more of a kindness to the city of South Milwaukee.

“It would really not be doing a justice to the city to have this boarded up,” he says. “So I keep it open as a retail space,” but he is not making even a tenth of what he first hoped for when he opened it.

And so, Lugauer is only blocks from Cucunato’s floral shop, but in other ways, they seem miles apart.

Cucunato moved her shop from Brady Street on Milwaukee’s bustling east side. She bought this building when rents on Brady Street went too high, moving last summer during the height of her busy wedding season. Without proper water hookup, she used the spigot in the building’s basement. She shows pictures of the brick fascia at the front of the building, then being held up with duct tape. Ultimately, she sold her home to pay for the renovations at her business.

Today, she is certain that her decision to move from that busy, eclectic Brady Street location to the deserted streets of downtown South Milwaukee was a solid one, even prescient.

What makes her so sure? Mostly, the city’s location, along the shoreline of Lake Michigan, between retail centers in Milwaukee to the north, and Racine to the south.

“It was culture shock, to be sure,” she admits, looking up and down Milwaukee Ave.’s empty sidewalk.

“But I will tell you this,” she adds. “This town is going to develop in spite of itself.”

* * * * * *

In May 2016, with residents seeming to reach an uneasy peace with Caterpillar, the city released its Comprehensive and Downtown Plan Update, detailing its economic development as it sought to deal with a high downtown vacancy rate (almost 25 percent) and changing economy.

“The major presence of Caterpillar’s Global Mining facilities within the downtown remains the city’s economic story,” the report read. “Indications are that Caterpillar intends to maintain its South Milwaukee operations.”

That same month, Caterpillar announced its plans to move engineering operations to Arizona, which would take about 200 jobs out of South Milwaukee.

Stephanie Hacker, the city’s newly-hired economic development director, helped write that report. Now, she’s helping make plans for what to do with the 750,000 square feet of space Caterpillar is vacating, as well as another 250,000 square feet of space that’s being emptied as another company moves to neighboring Racine County.

A million square feet of empty space is huge to a city this size. These decisions will define it, perhaps for generations. Hacker says it’s important not to rush. “As a planner, when you have a great foundation and great framework, the right project will come to you,” she says. “You just have to wait.”

What might be developed on the land? Hopes vary.

In August, the city was accepted into a statewide initiative that works with communities to advance downtown and urban corridor revitalization efforts.

“This town is going to develop in spite of itself.”

Mayor Brooks also has contacted state officials, who’ve announced plans to replace the Department of Administration’s aging office building in downtown Milwaukee with a new one. He hopes, rather than rebuilding there, they’ll consider taking over the Caterpillar complex.

“It’s a turnkey office, ready to go,” he says. “They could literally move 12 minutes from where they are right now, and have all the amenities we have here.”

And then there’s Foxconn’s 22-million-square-foot, 13,000-employee flat-screen manufacturing plant planned for Mount Pleasant, just 20 minutes south on I-94. (A project that many have serious misgivings about.) Suppliers and subcontractors may need manufacturing and office space. And workers will need places to live — sure, subdivisions will spring up in the farm fields of small towns nearby, “but we have a real strong story to tell about why to live in South Milwaukee,” Brooks says. “We are in that sweet spot of middle class housing and all the amenities that come with a small city.

“There are dozens of success stories, many within a 45-minute drive of us,” Brooks adds. “Others have done it. We can do it, too.”

Brooks is a part-time mayor with full-time worries, leading a small industrial city facing huge empty spaces and huge change.

“Historic decisions are being made right now,” he says.

He stops for a moment. Then adds: “I don’t want to be the mayor who screwed up the redevelopment of the Caterpillar land.

“We have to do this right.”

I think you are being delusional? optimistic? if you think there will be 13,000 jobs at Foxconn. Certainly not “middle class” ones.

They need to focus on businesses and functions that will actually bring people into the Central Business District. A movie theater complex, a chain sports pub, a Starbucks drive through, a grocer, etc. It must be a destination, and you need to start a multiplier effect. For the old factory site, maybe they can get an EPA grant to address any environmental mitigation issues. Maybe it can be packaged with a commercial/retail/office development. Maybe the rest can be redeveloped with New Urbanism housing, ensuring walkability and the need for services. They need to start think outside of the box immediately. Any Economic Development Director worth his or her salt would be able to easily start this process “yesterday” through comprehensive planning, and selling the community to the “right” investors and market components. If you are six months in and still don’t have a plan or any serious contacts or negotiations in place, find another one. This community of South Milwaukee needs to change it’s mentality in order to ensure that it survives over the next 40 years. Otherwise, it will face immediate urban decay and social decline.

Why would you put so many negatives in an article about a town that is working hard to make a comeback? Why didn’t you interview some of the positive businesses that are working very hard to pull businesses together and “ReStore” the downtown?

Why don’t you come to a lunch like the one at Barbieries today, January 16th and see all of the businesses networking?

You must have had a goal of negative when you started the article. You could have found out about the successful Evening on the Avenue festival the South Milwaukee Community and Business Association had and how that money will be working to start a community garden downtown or how they will use some of the money to market the businesses in the SMCBA.

You could have interviewed, Chris, the owner of C3 Designs who loves his new location or the President of the SMCBA about all of her projects and how people from the city nominated her for the Forty Under Forty award.

Thanks for helping bring our town down.