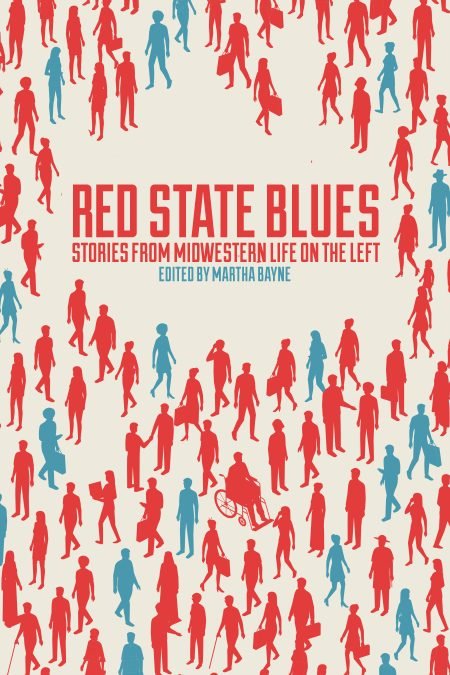

From the forthcoming Belt anthology “Red State Blues: Stories from Midwestern Life on the Left.”

By Allison Lynn

When I moved to Indianapolis in 2010, I imagined myself as an anthropologist — which, in retrospect, is a pretty rude way to move anywhere. But I was a native Northeasterner: I spent my childhood in Massachusetts, went to college in New Hampshire, and then lived for nearly two decades in New York City before my husband and I relocated to Indianapolis for university teaching jobs. With those jobs came the promise of no longer having to panic every time the rent was due, but at the cost of leaving my liberal bubble.

Sure, there had been Republicans in my circle in New York, but even at the time I understood that they were fake Republicans: socially liberal or financially greedy voters looking out for their own interests. One hedge funder I knew openly talked about how he intended to switch his party registration from Republican to Democrat as soon as he’d socked away his millions. He wasn’t a real Republican, just an idiot.

I started to understand that if Indianapolis is a blue bullseye in the middle of this doggedly red state, the bullseye grows bluer and bluer as you move toward its center.

Another woman-in-media friend attempted to vote in the Republican primary, only to find that her Greenwich Village polling place had no machines set up for GOP voters. “We didn’t expect any,” the poll workers apologized, giggling amongst themselves. On her walk home that day, my friend asked herself why, in fact, she was still registered Republican if she was pro-choice, pro-woman, and pro- so many other equal opportunities. She switched parties before the next election. She wasn’t a real Republican, just lazy.

But now, four decades into my life, I’d be moving to a place with actual Republicans as my neighbors. I steeled myself for debate and argument and a reckoning with why, exactly, so much of the country voted in ways that seemed a mystery to me.

Bring it on, I thought as I packed the car and headed west.

* * *

In his 2006 profile of Axl Rose in GQ magazine, John Jeremiah Sullivan writes: “Given the relevant maps and a pointer, I think I could convince even the most exacting minds that when the vast and blood-soaked jigsaw puzzle that is this country’s regional scheme coalesced into more or less its present configuration after the Civil War, somebody dropped a piece, which left a void, and they called the void Central Indiana. I’m not trying to say there’s no there there. I’m trying to say there’s no there.”

My first year in Indianapolis, I thought I understood what Sullivan was talking about. I had come to Indianapolis with my liberal talking points in hand, ready to argue and yell and maybe, after a few of the excellent Indiana microbrews I’d been reading about, to even listen to a different point of view. Quickly, though, I discovered that there were no raging arguments or debates at my local pub, and my new neighbors, if they were the ultra-conservative radicals I had expected, weren’t talking about it. Instead, the populace was quiet.

And frankly, so was the downtown scene. In fact, there was no sense of an active downtown at all. The city as a whole felt numb. When I asked where to eat, more than one local told me to head three hours up to Chicago for good food. As for shopping, a West Coast transplant explained to me that “Indianapolis is a good place to live, value-wise, but we do our consumption elsewhere, when we’re in California or New York.”

By my second year, though, Indianapolis began to undergo a dramatic cultural change, so much so that central Indiana was no longer a place you’d feel entirely comfortable describing as a void. Things peaked when chef Jonathan Brooks opened the restaurant Milktooth — serving modbar espressos and bruléed grapefruit and miso soup with pickled kombu — and landed on Bon Appetit’s list of “10 Best New Restaurants in America.” Down the street from me, Benjamin and Janneane Blevins opened a bookstore called PRINTeXT in a whitewashed single-room storefront whose tables were piled with stacked issues of Dissent and n+1 and Cherry Bombe and vintage literary magazines and journals where the essays appeared in both Lithuanian and English.

The there that began to fill in around me resembled more and more the there familiar to those of us from elsewhere. The city suddenly seemed full of hipster Latin-fusion restaurants and artisanal donut shops and experimental food trucks and legitimate tacos. As I type this, a restaurant serving $85 omakase meals is getting set to open.

My fourth year in the city, I was invited to an Easter egg hunt (chocolate eggs and coolers of microbrew) in my neighborhood, where the other guests were longtime Hoosiers, all of whom vote blue. This blew apart my theory that the blue streak running through Indy was entirely powered by transplants (the same transplants who were eating the legit tacos and Latin-fusion but couldn’t quite keep all of the artisanal donut shops in business). And it reminded me of all the judgmental shit I’d cast on Indianapolis before I arrived. So maybe it’s not that Indianapolis was undergoing so much change, at its core. Maybe it’s that I’d finally lived long enough in the place to begin to understand it — a process that doesn’t take months, or years, but years-and-years-and-years. Especially in a city where so much of what’s going on is under the surface.

I’ve been assured by people who’ve been here for decades that the food scene really is getting better. The food scene as a culinary development, they mean, not as an indicator of some sort of swing toward blue politically. The microbrew-swigging egg hunters assure me that city’s blue streak has a long history. Because while the city voted red in nearly every presidential election prior to 2004 (and has voted blue since), the democratic slice of those pre-2004 elections consistently hovered at around forty percent — sometimes nearing fifty. That’s not nothing. Especially in a state known as a conservative stronghold.

What is new, I’d argue, is the volume of that blue-streak’s voice. Thanks to Mike Pence’s attempts as Governor to wrest the state even further to the right, the political numb silence that greeted me in 2010 was replaced by serious Midwestern can-do in 2013. My neighbors rallied and wrote letters in support of same-sex marriage. Lawns on my block sprouted signs that read “Pence Must Go” and “Fire Pence: Your Rights Could Be Next.” My son, age 6, begged for an “Expel Pence” sign for his birthday. Everyone else already has one, Mom!

In Paris, I was cornered by two Americans.“You must know lots of people who voted for Trump,” they said, “in Indiana, and all.”

I started to understand that if Indianapolis is a blue bullseye in the middle of this doggedly red state, the bullseye grows bluer and bluer as you move toward its center, until you come to its very, very middle: the streets where my house sits. When I first moved in, a new friend described a woman on my street as “a good Democrat”—her way of explaining that the woman was someone I’d be glad to know.

It’s easy, as I write this from that street, to think the new blue voice has grown deafening. It’s only when I venture into the outer rings of the bullseye and beyond, that I’m reminded how truly atypical my neighborhood is. This grand change, this opening up, this loud blueness, this application of Midwestern can-do to defeating the far right — it isn’t happening all over. Drive an hour west of Indianapolis and, in reaction to the South Carolina statehouse debate, you’ll see trucks flying Confederate flags. In Greencastle, students of color tell me they’ve been pelted with sodas thrown from the windows of those same pickups. The Indiana I’ve experienced these last seven years is not the same that others know.

* * *

I was out of the country during Trump’s election. I had been in Paris for the year, where my husband and I were working on books. In the months after the vote, I commiserated with French friends, who themselves were nervous about Brexit and the specter of Le Pen. I traded worst-case-scenarios with the expats I knew — mostly other parents of kids at my son’s French (with a bilingual-English bent) school. We protest-marched together and followed Twitter and talked theories about the election during school potlucks. At one afternoon pickup in December, I was cornered by two dads, both American.

“You must know lots of people who voted for Trump,” they said, “in Indiana, and all.”

“You must know lots of people who voted for Trump,” they said, “in Indiana, and all.”

But here’s the thing: I couldn’t think of a single one. I explained this to them using the bullseye metaphor, a metaphor that quickly expanded into some sort of theory about the widening divisions in our country as a whole.

When I moved back to Indianapolis in the summer of 2017, I still couldn’t think of a single person I knew who would have voted for Trump. With this in mind, I attended a fundraiser for Rep. Andre Carson, the Democrat who represents the streets just south and west of mine— though my house falls one block into the district of Republican Susan Brooks. I arrived to the fundraiser feeling good. Our city’s got a Democrat in the House, and all of us who were gathered want to prop him up. There are a lot of us on the left, my friends and I told ourselves. We just need to ensure we’re heard. But then a young campaign donor asked Carson how he should talk to his own family members in the south of Indiana. He said that outside of Indianapolis, everywhere he goes all he meets are Trump voters who, nearly a year into this disastrous presidency, still see Trump as some sort of hero. “What should I say to them?” the young Democrat asked Carson.

Carson didn’t have an answer.

How do we talk to them? is really what the guy wanted to know.

It seems increasingly the answer is that we don’t.

Banner photo: Hoosiers expressing their opinion of Mike Pence when he was governor of Indiana; via Steve Baker/Flickr

Allison Lynn is the author of The Exiles (Little A/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) and Now You See It (Touchstone/Simon & Schuster), as well as articles, essays, and book reviews for publications that include The New York Times Book Review, People magazine, and Post Road. She lives in Indianapolis with her husband and son.