The legacy of a multiracial community on Indianapolis’s south side

By Susan B. Hyatt

One Saturday morning in 1960, high school senior Cleo Moore reported to work as usual. He worked at Regen Baking Company, one of two Jewish-owned bakeries then located in his southside Indianapolis neighborhood, where he cleaned the floors and scrubbed out the giant ovens that produced chewy rye bread, a favorite of local residents. Moore, who is Black, was a student at nearby Harry E. Wood High School. He had taken up wrestling that year, with some success. On that particular Saturday morning, young Cleo was surprised to be called to the front of the store to speak to his wrestling coach. The coach was there to ask the owner of the bakery, Mr. Regen, if Moore could be excused from work because he had made it into the city-wide wrestling tournament, which was taking place that afternoon. Regen said, “Of course he can go.”

Moore’s neighborhood, located on the near south side of Indianapolis, was a cluster of small houses and businesses. Meridian Street, the major thoroughfare running through the center of the neighborhood, was lined with Jewish-owned businesses: bakeries and grocery stores, small department stores and clothing shops. According to the late Max Eistandig, who, in 2005, compiled a tour of the neighborhood covering the 1920s and early ‘30s, it went like this: “Passo’s drugstore on the corner of McCarty and Meridian; then Shapiro’s, which began as a grocery store and later became a deli; then Sam Green’s barbershop; Gersten’s deli; a Chinese laundry; and another deli. And then there was Regen’s Baking Company.”

Until the post-World War II period, the neighborhood had been made up largely of African American residents and Jewish immigrants. Many African American families had migrated up from the south, fleeing the harshness of Jim Crow and economic hardship, while others had moved to Indianapolis from other northern industrial cities. They lived alongside their southside Jewish immigrant neighbors, most of whom had originated from two southern European cities located in what was then the Ottoman Empire: Monastir, now known as Bitola, which today is in North Macedonia; and Salonica, now known as Thessaloniki, today a major city in northern Greece. The break-up of the Empire and establishment of the newly independent countries of Greece, Turkey, and Yugoslavia had bred outbreaks of antisemitism in a region that had previously been largely tolerant of religious diversity.

The story of Cleo Moore’s relationship with Regan’s is one example of the way Black and Jewish community members lived and worked together in this neighborhood well into the twentieth century. Moore kept moving on to the next level in the wrestling tournament, and each time, Regan would excuse him from work so he could go compete. That year, 1960, Moore won the state championship. “That was just so gratifying,” Moore said in an interview in 2011. “I still didn’t realize what it all meant. In any event, it was because of Regen’s Bakery—I was more dedicated to them than to anything at school. But, by winning that tournament, I was able to go on to college. No one in my family had gone to college before—no one. I was able to get a wrestling scholarship and go on with my education.”

The only remaining clue to South Meridian’s former life as a major Jewish shopping strip—and of the community life that happened there—is Shapiro’s Kosher-Style Deli, a beloved Indianapolis institution that still stands at the corner of McCarty and Meridian Streets. That same intersection was also once home to another Jewish-owned business, Passo’s Drug Store. In 1976, a gas main exploded, destroying the pharmacy. The Passo brothers who owned the business, Al and Izzy, decided not to re-open, allowing Shapiro’s the space to expand into the footprint it occupies today. Passo’s is still fondly remembered by former southsiders because it had a soda fountain where Black and white teenagers freely mingled, enjoying cherry cokes together.

Today, when you drive south on Meridian Street from downtown, once you cross McCarty Street, you encounter an odd mix of empty lots and mismatched structures that seem randomly scattered across the streetscape. You will drive under an overpass that is part of Interstate 70, which cut an angry swath across the part of the neighborhood that had once been a dense conglomeration of houses and small businesses. If you are at all familiar with the history of urban redevelopment in the twentieth century, you already know that this was a typical pattern in American cities. Between the late 1950s and the late 1970s, the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act funded the construction of a network of interstate highways that bisected mostly African American and immigrant neighborhoods. This resulted in the imposition of both physical and social barriers that divided communities and displaced thousands, if not millions of residents who were never fairly compensated for the seizure of their properties.

Support independent, context-driven regional writing.

I learned of the near southside neighborhood while attending a workshop on funding for community-based projects. The woman sitting next to me shared the story of how her neighborhood had been destroyed by the construction of an interstate highway, and told me that every summer, the former residents continued to return to the old neighborhood for a reunion. I teach Anthropology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), and the story of a local neighborhood, whose previous residents still felt so attached to that space that they continued to commemorate it year after year, struck me as a great focus for my spring ethnographic methods course. So that year, we undertook an oral history project we called “The Neighborhood of Saturdays,” which focused on documenting life in this neighborhood from the 1910s up to the construction of Interstate 70, in the early 1970s.

We arrived at the name for our project in consultation with a committee of former Black and Jewish southsiders, whom we had assembled to oversee the project. Fifty years (or so) ago, they had all become part of a southside diaspora, as displacement for some and upward mobility for others had scattered people across the city. We adopted the name in recognition of two important aspects of the neighborhood and its history. First, there was the significance of the yearly picnics, which always take place on the First Saturday in August. These gatherings bring together former southsiders, mostly African American, who enjoy a day of celebration, where they renew ties of friendship and kinship and reminisce about growing up on the old southside. When I attended my first picnic, in 2009, I asked folks why the neighborhood had been so important to them. Many of them recalled fondly their Jewish neighbors, kids they had grown up with, whom they had not seen in over fifty years. That sent me on a search, which was ultimately successful, to find some of these former Jewish neighbors. So, the “Saturday” in the project name also references the Jewish observance of the Sabbath on Saturdays.

Over the next five years, we collected hundreds of documents and stories from community members, among them Cleo Moore. When Moore was still a young boy, his family was forced to flee their hometown of Canton, Mississippi, because his uncle had killed a white man during an altercation. The family slipped away in the middle of the night, heading north. Somehow, both of these groups, African Americans and Jews, ended up crowding together, seeking safe harbor in this relatively small quarter on Indianapolis’s south side.

After World War II, the young Jewish men who had returned from the war were able to access higher education through the GI bill. In the northern part of the city, new neighborhoods were springing up, with larger footprints and enclosed yards. The availability of low-interest VA loans made it possible for Jewish families to relocate to these more bucolic environs. African-American veterans were not afforded the same benefits of these federal programs, even though they should have been entitled to them. But their families, too, scattered as the giant maw of the interstate began to eat through their homes and businesses.

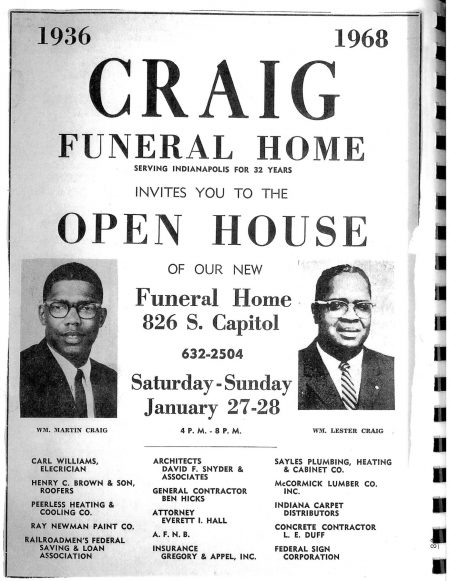

Craig Funeral Home ad for an open house at their second location. Image courtesy the Neighborhood of Saturdays archive.

The interstate had a huge influence on the life of another southsider, Mr. William Craig. In 1936, his father and his uncle had established Craig Brothers Funeral Home, a Black-owned business on the near southside. In 1974, the senior Mr. Craig passed away, leaving his son, also named William, to take over the business. Their first location, at 1002 South Senate Street, was seized a year later through eminent domain for the construction of I-70. As he tells the story, Mr. Craig went down to the Indianapolis City-County Building to study the blueprints for the next phase of I-70 construction. There were, at that time, no plans to build additional ramps in the neighborhood so in 1975, he bought a building at 826 S. Capitol Avenue that had belonged to the Schwartz family.

The Schwartzes ran a small grocery store on the ground floor of that property and lived in an apartment above. (They were also reputed to have the best candy selection on the southside, and Henrietta Schwartz Mervis told us that her father had traveled throughout the Midwest, seeking out the choicest sweets). They, too, were joining the Jewish exodus northward. After Mr. Craig bought the building and relocated his business, he discovered that there were new plans to build yet another entrance onto I-70 from Capitol Avenue to alleviate the high volume of traffic on an adjacent artery. Forced to move again, Mr. Craig left the southside for good. (His family still operates Craig Funeral Home, but it is now located on North College Avenue.) And, if you drive south on Capitol Street today, perhaps in search of the old landmarks you have just read about, you might suddenly find yourself whizzing onto I-70 westbound, hurtling toward the airport or, if you were to keep going, all the way to St. Louis. There is no signage indicating that this part of the street is now, essentially, an entrance ramp onto the highway.

From 2009 to 2013, the former southsiders continued to meet and work with students who conducted oral history interviews and carried out archival research on the community. One of our favorite activities was the so-called “scan-a-thons.” We would send out a call for folks to bring old photos, church and synagogue bulletins, newsletters, and any other memorabilia they had squirreled away about the old neighborhood to these events, where we would use portable scanners and laptops to scan their materials while they waited and chatted with one another and with the students. Some of our best stories were gathered at the scan-a-thons. We then archived the digital images, now more than four hundred items, on a website maintained by our library’s Center for Digital Scholarship. We also used this material to produce a student-authored book about the neighborhood. We held the scan-a-thons at several different locations, including the synagogue where many of the former Jewish southsiders now worship; the South Calvary Missionary Baptist Church, still located in the old neighborhood; and at a southside community center which had originally begun its existence in the late 1800s as a settlement house created to serve the needs of newly arrived Jewish immigrants.

Cleo Moore in 2012, holding his wrestling championship award from 1960. Image courtesy Susan B. Hyatt.

Even after the courses were over, we still met regularly to plan events, including a tour of the old south side for Samuel Freedman, the religion columnist from the New York Times, who visited us and wrote a story about the project in Spring 2012. Students who had participated in the classes in 2010 and 2011 continued to attend meetings and assist with various ongoing activities. On one such occasion, at a planning meeting held in the basement of South Calvary Baptist Church, one of the Jewish elders asked a question intended to be innocent but which the group perceived as slightly off-color. “When was this church erected?” Gladys asked, occasioning an outburst of laughter from everyone present. Later on, the students who had been present were somewhat scathing in their recollection of that conversation and of the hilarity it had provoked. “It was like they were all in the eighth grade,” they sniffed.

And, in a way, that was the point: our project brought people back to a time in their lives that they cherished. As children, despite the poverty and privations that they had all endured, along with the racism and antisemitism, our elders had been raised up by a community that was bent on sustaining a kind of everyday civility, even while much of the rest of Indianapolis was rigidly segregated. The jokes and gentle teasing and laughter that punctuated our meetings came easily because they were the product of the kind of intimacy shared by those who grow up together, which stays with a person into old age.

It turned out that Mr. Regen’s confidence in young Cleo was well-placed. Mr. Moore went on to teach history and coach wrestling at his former high school and later on, he became a community leader in many civic organizations. Furthermore, his family established a small scholarship fund – “one that’s designed to encourage the kids to go on to school,” he told us. He continued, “My youngest brother went on to college and now he’s a doctor in Marion, Indiana. There are others who are continuing to benefit. It’s not a big scholarship. It’s just designed to encourage them to go to school, like I did.”

By the end of our project, we realized that what we had unearthed through our research was not just the story of a unique neighborhood that most people in the city either had never known about or no longer remembered; more importantly, we had also uncovered a tender web of attachments that had long lain dormant but that were now, once again, reanimated. The stories they shared with us have become all the more precious now, as our stalwart elders have begun to fail. We have lost many of them since we first began our work ten years ago.

Our work is now moving on to a new phase. The children of the elders, who are now in their Sixties, would like us to do a follow-up project about their experiences growing up. Somewhat paradoxically, as the old neighborhood broke up, families moved into neighborhoods that were much less integrated than the old southside had been. A new group of students and I will launch this undertaking this spring, which will focus on the music and popular culture of the sixties and seventies and will recount the very different experiences that the children had, growing up in either largely white or largely Black environments. The title of this new undertaking? The Neighborhood of Saturday Nights. ■

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to everyone, especially elders and students, who contributed to the Neighborhood of Saturdays project. Special thanks to the Moore, Shapiro and Passo families. Appreciation is also due to the librarians in the Center for Digital Scholarship at IUPUI’s University Library, to my colleague Paul Mullins for assistance with locating digital resources, and to Angela Herrmann for her careful editing and excellent suggestions.

This story was produced in partnership with Indiana Humanities’ INseparable project. Read more stories in the series here.

This story was produced in partnership with Indiana Humanities’ INseparable project. Read more stories in the series here.

Susan B. Hyatt is a former community organizer, a current Professor of Anthropology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, and a lover of Midwestern cities.

Cover image: a postcard of Shapiro’s Deli, courtesy of the Shapiro family.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.