By Scott Atkinson

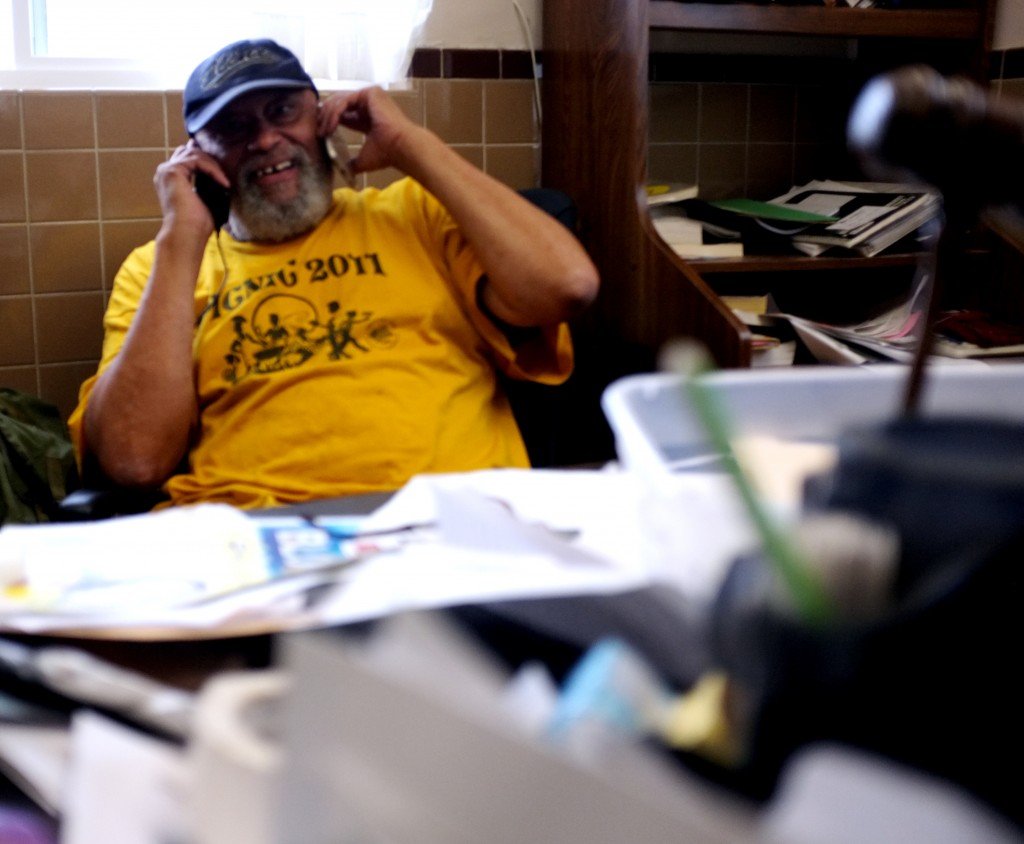

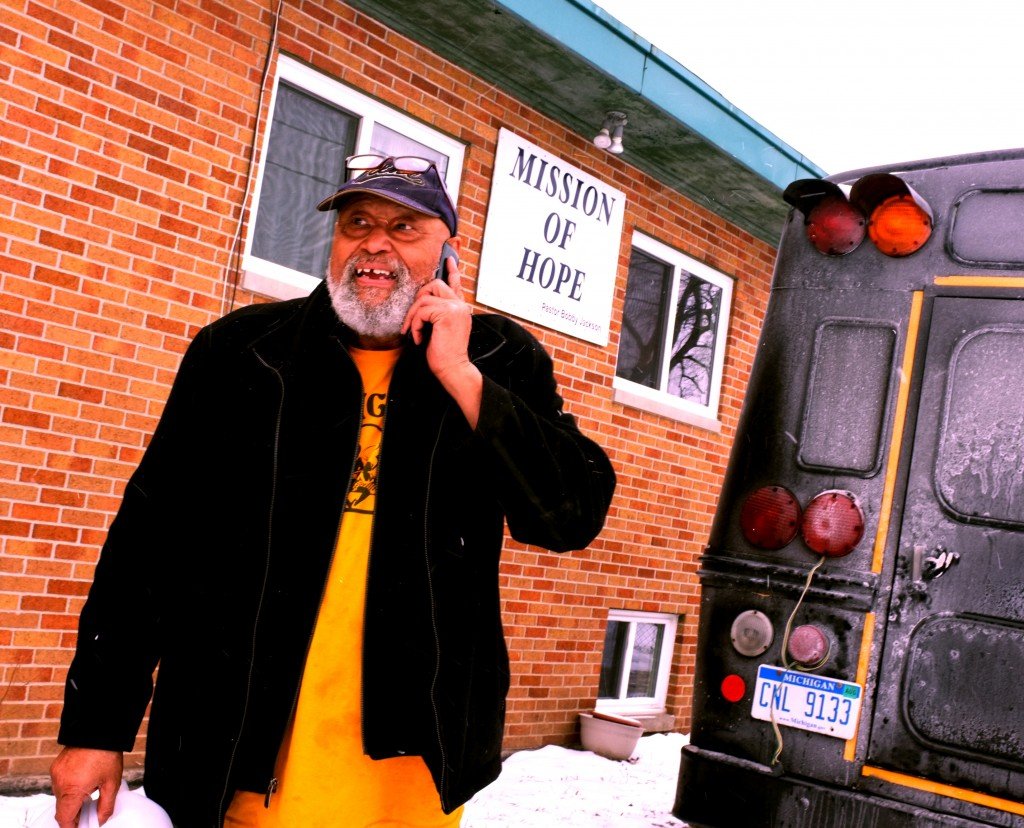

Michigan Governor Rick Snyder was on his way to Flint to spend some quality time with reporters dodging questions about whether or not he — or the guy who recently resigned from the Department of Environmental Quality, or just who, exactly — was responsible for the lead that had found its way into Flint’s water supply and had been poisoning kids for almost a year. But Bobby Jackson wasn’t worried about the governor, or what he would say, or even that he was making his way to city hall. Pastor Bobby Jackson does not have time for that. Before I left him at his office of Mission of Hope, the independent homeless shelter he runs, he had a cell phone on each ear, on hold with two different people, while he tried to read email with his assistant leaning over his cluttered desk, plunking keys and reading subject lines like, “Can I Help?”

So, no, Pastor Bobby did not have time for Snyder. He barely had time for the two people he would eventually hang up on as the phones rang and rang, let alone politics, which he steers away from and speaks of — as he does many things — in biblical terms. You can no more control the actions of the governor than you can God, or the devil.

All you can do, Pastor Bobby says, is love people.

And give them water.

[blocktext align=”right”] All you can do, Pastor Bobby says, is love people.

And give them water.[/blocktext]That’s why I wanted to meet Pastor Bobby. Amid the crisis in Flint, with the ensuing media circus (a good thing) and the quick-to-talk but slow-to-act state government coming to town, Pastor Bobby was at his small shelter in a largely abandoned north Flint neighborhood, trying to make sure people had some water to drink. He is the water guy.

The shelter is located just off Industrial Avenue, so named for the 258 acres across the street where so many factories once stood, employing 27,000 people, that it was known as Buick City. It’s empty now, all except for a patch that is home to a pipe-making plant, where several sections of the KWA Pipeline are being built in 50-foot sections of pipe wide enough for a tall man to just have to stoop to walk through. The pipeline is a $258 million project that will connect Flint and Genesee County directly to Lake Huron, 74 miles away, so they no longer have to buy their water from Detroit. Had everyone been a little more patient and a little less cheap (the pipeline is expected to be finished this year) no one outside of Michigan would have ever heard about the Flint River.

Mission of Hope is just a few blocks away, neighbor to enough boarded up and slumped-over homes that even Pastor Bobby says it looks like a war zone.

It’s a small shelter, with a kitchen, library, and sitting area upstairs. In the basement are two storage rooms and a small sanctuary with a handful of pews, each just big enough to seat three people who don’t mind if their shoulders touch, and a small organ in the back. By the time I left, the pews would all have been pushed to the side to make room for cases of water.

“Nobody can sit in my church!” Pastor Bobby says, and like most the things he says, it comes out sounding like a good thing. A blessing. Spend enough time with Pastor Bobby, and you can’t help but see blessings anywhere you look. If you don’t see them, he’ll point them out to you.

* * *

Pastor Bobby Jackson runs the Mission of Hope shelter on Flint’s north side. After recently making the national news, he’s running out of room for the water being donated, but he’s already preparing for when that water runs out.

Here, in a nutshell, is what happened: Flint, for years, has bought its water from Detroit. In an effort to save costs throughout Flint and the rest of Genesee County, the county and city reached an agreement to have the pipeline built to be in charge of their own, cheaper water. But it wasn’t going to be cheap soon enough after an emergency manager, appointed by Snyder, came to Flint and floated the idea that in order to save costs in the interim (Flint’s budget was in shambles) they could switch their drinking water supply to the Flint River. It did not seem, at the time, such a bad idea. After all, the city had long ago used the river as a water source. The difference is that river water is harder to treat. It has to be more closely monitored depending on what might be running off streets or farmers’ fields when it rains. It is also naturally more corrosive. If you don’t treat it properly — as it wasn’t in Flint — it corrodes the pipes it runs through, and if your city has old pipes, as in Flint, that means they have lead in them, and that means the lead is in the water and you have some big, big, problems.

[blocktext align=”left”]“Instead of turning the river red, he turned it to lead.”[/blocktext]You have bigger problems when there are reports of lead in the water that go ignored, and a state government tells its people, over and over, that the water is fine, and so those people, including kids, drink that water until a pediatrician and some local researchers find out that it is not fine, and has, in fact, not been fine — has in fact been poisonous — for about a year.

So, a big problem, an almost insurmountable, very expensive problem. About $12 million from the city, state, and a local charitable foundation has been already spent just to switch the city’s water supply back to Detroit. Millions more will need to be spent to replace the corroded pipes that could leach lead for who knows how much longer now that the protective coating is gone. It’s a big enough problem that Pastor Bobby doesn’t think about it just in terms of pipes and protective phosphates. He thinks of Moses.

In particular, he thinks of the story of Moses going into Egypt to save the Jews, and God turning the river to blood, turning it red.

“Instead of turning the river red, he turned it to lead,” Pastor Bobby says, sitting in his office, once again on hold.

* * *

Andrew Betts, 37, helps reorganize donated water at the Mission of Hope shelter in North Flint, Michigan. “I’m so happy,” he said when he arrived that morning, walker into Pastor Bobby Jackson’s office.

I do not have Pastor Bobby to myself. Just days prior to my visit he had been on MSNBC, being hailed as one of the people getting water to those who need it, and since then the donations have come in Noah-like proportions. As more people enter the shelter they help move stacks of water bottle cases. Children climb on them as though they’re playground equipment. I have to wait while he finishes a phone interview, and for a time I tag-team interview him with someone from the Washington Post. They, like me, have descended upon him because he’s become the water guy, the guy on the front lines of a crisis he does not need to read the paper to know about.

When we get a moment, I ask him about becoming Flint’s water guy.

Sitting at his cluttered desk, he gives me a friendly but level look, as though what he’s about to say is either very important, or very obvious.

“Okay, it’s interesting because — I’ve always been a water guy. Because people living in abandoned buildings, and people who have shut-offs in their regular houses, would come here and get water. But then they had to get their own buckets then, and I let them get water,” he says. “That utility room there? It’s got a sink about this deep, so you can set a big bucket down there. But they bring what they can carry, gallon jugs or whatever they can come up with.” His phone has been ringing while he talks. “Let me get this, because it might be the sheriff,” he says. “Mission of Hope, this is Bobby, how may I help you? Very good, how are you today? Real good, I’m being blessed — I’m really, I’m feeling like I can be a testimony of how they say God can pour out blessings on you more than you can handle? I’m really grateful.”

* * *

Pastor Bobby Jackson runs the Mission of Hope shelter on Flint’s north side. After recently making the national news, he’s running out of room for the water being donated, but he’s already preparing for when that water runs out.

Pastor Bobby has almost more water than he can store, but he does not have any paper. No one knows that Pastor Bobby needs paper — regular old printer paper. So he and his volunteers, when they need to start printing fliers (he’s decided that the smart thing to do is to distribute information about water, like that that you can shower with it but not drink it, for example) are scrounging for any used paper they can find, so they can print on the other side.

Pastor Bobby also has no running water. (He spends several minutes on hold with Flint’s water department, before hanging up to focus on other things.) His water was shut off in November after he couldn’t keep up with the bills. (Flint’s water, despite being poisonous, is not cheap. It costs citizens an average of $140 a month, according to the local newspaper, The Flint Journal, and that was an increase in price after the city made the switch to the cheaper river. In November, the city sent out 1,800 shutoff notices for people who hadn’t been paying, and more are being sent out now.) He couldn’t drink it, but he could at least flush his toilet or let people from the neighborhood — homeless or unable to afford their own undrinkable running water — take a shower. When one of his volunteers insists he knows how to flush the toilet by pouring collected rain water in the bowl, Pastor Bobby gently interrupts as many times as he needs to tell him that he cannot use the gallon jugs to flush. He has to pour those into a larger, five-gallon bucket next to the toilet, “so you get that big whoosh.”

Mission of Hope runs solely on donations, which means that sometimes the water or the electricity get turned off. When he lost power in June, it wasn’t as big of a deal. People could still come in, but when winter neared, he needed heat. When he first opened the shelter eight years ago, he saw what other nonprofits had to do, scrabbling to keep their funding, to meet grant requirements — sometimes just to keep their jobs. He didn’t want to have to do any of that. Love doesn’t fit on a government form, he says, and so he runs completely on donations, which means that occasionally there are no lights or running water, but also that the people who come in don’t have to qualify their need for help. He feeds them breakfast (“Anything I can conjure. Sometimes it’s pizza.”) and gives them mailboxes in the office so they can have a mailing address to use for job applications. There’s an old, thin sleeping bag on top of the bookshelf in his office that’s rolled and tied with a necktie, waiting for whoever needs it.

Our conversation is interrupted by another phone call.

“I’ve got water for you, my dear, so you come right on over and I’ve got three or four cases for you. That way you won’t have to schlep all the way over here again. You come right now. Bye bye.” Pastor Bobby looks back at me. “That’s a lady with a disability. She comes from way across town because we were the only ones doing this for the longest. People get accustomed to coming here.”

* * *

Pastor Bobby Jackson runs the Mission of Hope shelter on Flint’s north side. After recently making the national news, he’s running out of room for the water being donated, but he’s already preparing for when that water runs out.

“He’s pouring it on me, Scott,” Pastor Bobby says, talking about God, when he gets off the phone again, knowing yet more water is on the way, and having secured a U-Haul truck in which he can store it all. (“I’ll be like a squirrel and be able to pull it out when I need it.”)

For Pastor Bobby, the moment is proof that keeping faith and not quitting pays off. An ex-military man, he said one of the first things he learned in basic training was that you do not leave your post until you are relieved by your command, and God has a habit of not speaking up very often.

He’s so happy. In his business, if it can be called a business, you need to be. It’s a particular kind of happiness, a Flint happiness, not meaning so much that you’re happy, but that you’re happy anyway. You’re happy even when you see a couple of guys you just handed water to selling that same water a few blocks away. You’re happy that your shelter has only been broken into twice in eight years (“That’s wonderful!”), and that second time, just a few days ago, when all the thieves took was your reinforced metal door meant to keep them out? You love them with all your heart.

“They didn’t even come in and take a thing, and I love ‘em. I love ‘em!” He takes a break to laugh. “I love ‘em! I mean, they could have come in here and taken the computer and, I mean, there isn’t much more that’s valuable, but I believe the glass is either half-empty or half-full, and whatever it is, you gotta go from there forward.”

* * *

Just one room full of donated water of Pastor Bobby Jackson’s shelter, Mission of Hope, which has been receiving massive donations since he appeared on MSNBC to talk about the current water crisis in Flint.

Before I left him, I was again waiting while he was talking on the phone about all the water that had been donated, but this time he wasn’t talking about blessings or the gifts from God. He is an optimist, but he is also a realist. He’s also a man of the bible, after all, and he knows how the stories go, that alongside the miracles come the fire and brimstone, the floods, all the Jobs of the world.

“Two months from now, this will all go away,” he says into the phone, “and I’m going to be scrambling again.”

___

Scott Atkinson is a freelance writer based in Flint, Michigan. For the past several years he has been an award-winning features writer for The Flint Journal. He teaches writing at The University of Michigan-Flint.

All photos by Scott Atkinson

This month (January 2016) only, become a Lifetime Member of Belt! Never worry about renewing your membership again; save 50% on anything we ever sell, forever; and support local journalism and independent small press by enabling us to pay writers for their work.

Your post story on Pastor Bobby was enlightening and uplifting on how much and how well one person can make a difference when they are determined and disciplined to do good for others. It is job well done.

Pastor Bobby is doing great work.

His work need to in Andhra Pradesh India.Because 80% of people every day buy the water. So many people effected viral diseases due to salt and florid water.

Greetings from George,Evangelist in India

First let me thank god almighty to paved the way to us.

A few seconds I would like to talk you by mail

http://group spaces.com/Church of Christ and Social Service/

Please read, and then tell your opinion.

Please watch my all work details in Google: George Raju Vara

Thanking you

Your brother in Christ

George

Ps: Search Andhra Pradesh water problem in Google.

Pastor Bobby , a noble soul to be sure and a true and loving pastor to his flock. I knew a Bobby Jackson growing up on the South side of Flint and that Bobby Jackson had a cousin Melvin Jackson. We played baseball on a little scrub team and Melvins Mom took the whole team to see the freedom train,back in the 50,s

The Jacksons I knew were fine people and have left me with fond memories, I believe Melvin has gone on,I can remember his smile and also that of his cousin Bobby.