“By the hoboes, for the hoboes, of the hoboes.”

By Marc Blanc

It doesn’t take many days in St. Louis to learn that the city is constituted with the names of the rich and white, the dead and old. Nineteenth-century beer barons endure as street signs long after their draughts stopped flowing. Dogfood moguls lend their names to entire college campuses, and it’s impossible to forget that the major institutes of art and culture are brought to you by a handful of banking dynasties. Busch, Danforth, and Kemper might sound familiar to those outside of St. Louis, but there is one ubiquitous local name that seems to be ours alone – that of the Eads family.

They are among the oldest and richest of those already old and rich St. Louis families. The patriarch, James Buchanan Eads, worked modest jobs on Mississippi River steamboats in the early nineteenth century before developing a diving bell that could plunge men into the depths of the river, where they would salvage goods lost in shipping accidents. Businesses and families alike were willing to spend big for the recovery of their possessions, resulting in a fortune for the self-educated Eads.

Eads immortalized his family name in stone and steel in 1874, when he completed the titanic Eads Bridge, forever connecting St. Louis to East St. Louis over the Mississippi. At the behest of the city government and his friends in the railroad industry, Eads constructed the bridge to ease the flow of railway commerce into the river town. With ingenuity, generous tax breaks, and the lives of over a dozen construction workers, Eads built something more than a bridge. He built a monument to his own engineering genius and to the triumph of free trade over nature’s obstacles. A most American mythology.

However, a counter-mythology hides in the shadow of the Eads Bridge. While most St. Louisans know James Buchanan Eads, his grandson James Eads How is consigned to the margins of even local history, where if he is remembered at all it is as an eccentric curiosity. In 1898, the younger James attained celebrity for spurning his inheritance to the family fortune and living as a shabbily dressed itinerant worker. After the death of James’s father that year, a nationally circulated article announced that “the millionaire grandson of James B. Eads has given up luxuries and a palace in St. Louis for plain living and missionary work in the slums of the city.” The press faithfully reported on the young man’s charitable acts for the next ten years, when newspapers began to call him the “millionaire tramp.” James spent his adult life riding the rails, looking for temporary manual labor and dipping into his funds only to finance his mutual aid society, the International Brotherhood Welfare Association (IBWA).

Initially, the IBWA was known for the “Hobo Colleges” that it established across the Midwest, with active operations in St. Louis, Chicago, and Cincinnati. A Harvard man, James organized and sometimes taught classes on law, public speaking, and history to the train-hoppers who happened to be in town en route to their next job. Asked why he spent his time teaching wandering laborers when he could have been lavishing in luxury, James would repeat what he had allegedly said to the mayor of St. Louis when he requested that all $20,000 of the inheritance from his father go to the city’s poor instead – “Whose money is this? I didn’t do anything for this.” James decided that his family fortune rightfully belonged to members of America’s most precarious workforce, the temporarily employed and constantly traveling class known then as “hoboes.”

James Eads How around 1918.

While no historian has concluded why James felt that this particular population possessed the best claim to his millions, his decision makes a certain sense considering his family’s businesses. James’ father, James Flintham How, was an executive of the Wabash Railroad, one of the most succesful railways in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century Midwest. Wabash connected Ohio to Kansas City, stretching north to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. It’s likely that from an early age James heard about an underclass of men who illegally stowed away on the company cars, denying his father’s side of the family their train fares and his mother’s side their bridge tolls.

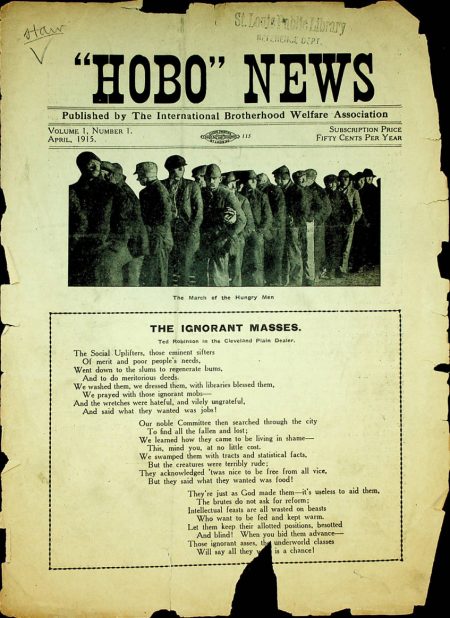

Railroads deployed police as well as public sentiment to vilify migrant workers and prevent them from taking money out of the company pocket. James undid quite a bit of Wabash’s efforts in 1915 when his mother died, leaving him in possession of his full inheritance. The tramp king immediately put his money toward what would become his seldom-cited contribution to radical American literature, a monthly magazine called the Hobo News.

Printed first in St. Louis and later in Cincinnati, the Hobo News is an unusual artifact in the history of American radical publishing. Although kept afloat by an obscenely rich man, the magazine honored the voices of the dispossessed for whom it claimed to speak. While James contributed an editorial to each issue, the masthead included several self-identified hoboes who produced the bulk of the paper’s original writing.

Inaugural issue of Hobo News, April 1915.

The paper’s reportage consisted mainly of first-person accounts of working life on the road. In a 1918 article, Will J. Quirke, a regular contributor, recalls his experience as a prisoner of a chain gang. Quirke writes that he train-hopped to Jacksonville, Florida in response to an advertisement promising high wages for “mechanics and laborers of all kinds,” only to find that the advertisement was a rouse for luring and imprisoning migrants to extort fines from them under an anti-vagrancy law. Quirke describes the horrifying violence inflicted on him and his fellow workers in custody. “For the least offense, the prisoners were stripped, laid across a barrel … I saw a big negro get fifty lashes for sassing a guard—the flesh pulled off his back—blood and skin adhering to the strap.”

For Quirke’s contemporary readers, the story offers a practical warning to be wary of advertisements promising work in the South unless one owns “a bank account, a good suit, a mileage book and a tin can badge with the inscription ‘Special Detective.’” For readers in 2023, Quirke’s article offers a window into a misrepresented subculture. Over a century’s worth of popular culture has portrayed hoboes as almost invariably white and never as the victims of overt state violence. Yet Quirke witnessed Black itinerant workers who were subjected to the atrocities of slavery in the legalized form of chain gangs and anti-vagrancy laws. Over its fifteen-year run, Hobo News presented numerous similar scenes of working-class life from the perspectives of some of those who lived it the hardest, accounts that challenge modern assumptions about the hobo experience.

Portrait of Bill Quirke, 1918.

James Eads How exercised the lightest of editorial hands, evidenced by the non-standardized “hobo vernacular” that writers such as Quirke freely employed. Quirke illustrates one injustice of the chain gangs with heavy slang: “If a gink gets arrested and sentenced to time in the Cally if he has a few dollars or a good Benny, they give him every opportunity to get away from the working gang, so they can appropriate his money or clothes” [Translation: If a hobo with some money and decent clothing is arrested and works on a chain gang, the officers will steal his cash and sell his clothes].

Hobo News’ use of this class-based dialect is as fundamental to its radicalism as the content of its journalism. The magazine’s motto, “by the hoboes, for the hoboes, of the hoboes,” declares James’ intention to cultivate a distinct class consciousness among migratory workers. An effort focused specifically on hoboes was necessary because other centers of working-class power did not often welcome the migrant class into the organized labor movement. Outright hostility was more common than gestures of solidarity, even from radical leftists. For example, during the St. Louis General Strike of 1877, one member of the socialist Workingmen’s Party publicly denounced the “tramps and vagrants” to whom mainstream newspapers libelously compared the striking railroad workers.

Against this vitriol, James claimed that his magazine’s primary ambition was to “make the word ‘hobo’ respectable.” To accomplish this, he and his staff used hobo slang, as well as ribald, absurd, and sometimes twisted humor. One headline announces “Beer-Crazed Mule Commits Suicide.” Such articles appeared alongside earnest appeals to the more respected sections of the working class. In an editorial from the second issue, James tries to persuade labor leaders to pay more attention to their migrant brethren if only because underemployment caused migrants to cross the picket line during strikes. “No Union man, no matter how skillful his craft or how good his wages, can consider himself and his family safe while such conditions exist. The strike-breakers are all taken from this class [of migrant workers].” James’s voice in the Hobo News mediates the relationship between hoboes and the marginally more privileged workers who were also reading the magazine. Drawing on his education at Harvard and Meadville Theological Seminary, he does not write in hobo dialect, opting instead for an “enlightened” Christian rhetoric inspired by the social gospel. He announces that the magazine is “against Commercialism, Unemployment and War and in favor of Co-operation, Brotherhood and Peace.”

The January 1918 cover depicts migrant workers beneath the St. Louis bridge engineered by

James Eads How’s famous father, with a somewhat ironic “Happy New Year” greeting.

James’s ability to build a rhetorical bridge between the hoboes and more steadily employed readers worked in the Hobo News’ favor, if the magazine’s circulation is a reliable measure. The magazine was certainly the most widely distributed publication of its kind, peaking at 20,000 copies per issue in 1919. Still, James was not without his critics. The editor exacerbated a rivalry with the International Workers of the World (Wobblies) in the pages of the Hobo News, critiquing the Wobblies’ militancy and questioning their compassion for itinerant labor. The Wobblies, according to the historian John Lennon in his book Boxcar Politics, saw James as “an eccentric millionaire who had no authentic connection to the work.”

The Wobblies had some ground to stand on in their criticism. James’ attitude toward hoboes was not always as fraternal as it was patronizing. “We’ve got to organize these men,” he once told a reporter. “But first we’ve got to educate them. Most of them have minds like children, and they don’t know what organization means.”

He premised his work on the belief that hoboes did not truly wish to live as hoboes. Rather, he claimed, they were victims of a volatile and unjust economic order that could not provide steady employment, a systemic failure that tempted hoboes to sinful habits like gambling and overdrinking. James believed that he had to educate them and lift them out of their degraded status, just as urgently as he had to educate polite society about their struggle. However, as Lennon argues, not all hoboes traveled because they couldn’t find work. Many actively chose to live on the rails because it freed them from the managed regimentation of industrial labor. Two former hoboes, Jack London and his boxcar mentor “A-No. 1,” fit this category of willing migrant. “The greatest charm of tramp-life,” London waxes in his 1907 hobo memoir, The Road, “is the absence of monotony.” Holding down the rails was, for London, “an ever changing phantasmagoria, where the impossible happens and the unexpected jumps out of the bushes at every turn.” While presenting its own challenges, itinerancy offered liberty, community, and a more organic rhythm of work than the grueling factory shifts most urban Americans endured by the early twentieth century.

What cannot be said of James, however, is that he didn’t live out his principles. He honored his vow of peripatetic poverty until he died in 1930, perishing from pneumonia exacerbated by severe malnutrition. James’ life was a social revolution concentrated in a single individual. His work was a direct rejection of the gospel of wealth with which he was raised, and he believed in the inevitability of a freer and more just society, if only enough people would struggle for it. Maybe this is why the Eads family papers only include a handful of impersonal documents mentioning James. James Buchanan Eads impacted his world with commerce and steel; James Eads How did the same with paper and charity. Paper may perish much faster than steel, but personal immortality was never James’ goal.

The gradual, complete eradication of inequality, on the other hand, was his goal. In its small way, the Hobo News made strides toward even this immense dream. James blurred the distinctions between consumer, sales agent, and stakeholder by encouraging readers to sell their copies of the magazine in the “Jungles” and “Hobohemias” through which they passed. Not only did this distribution model allow the magazine to quickly spread across the country, but it challenged the burgeoning hegemony of copyright law and corporatization in American publishing. The “hustlers” of the Hobo News differed from other sales agents because they did not have to split their earnings with James or any of the magazine’s executive committee. Neither did the magazine show any qualms with reprinting articles from larger publications without attribution—most reprints were articles by sympathetic authors such as Jack London and Ambrose Bierce, unlikely to object to a socialistic hobo paper making use of their radical words. The Hobo News must therefore be one of the only twentieth-century publications that was simultaneously the product of a single millionaire and a collectivist, anti-profit enterprise of the dispossessed.

Members of the International Brotherhood Welfare Society, who also likely sold the Hobo News as they traveled across the country looking for work.

The dialect of the Hobo News has yellowed like the paper on which it was printed—although if you want to brush up on “Hoboese,” the October 1919 issue features a glossary of common hobo slang. The reality of migrant labor in this country, however, is just palpable now as it was in the 1910s. Up to three million people in the U.S. leave their homes to find work every year. Most twenty-first-century migrants in the States are Latino and do not resemble James’ hoboes in physical appearance or cultural practice, but current labor organizers can still learn much from James’ compassion for a forgotten proletariat. Unions must attend to the needs of these populations, and their vernacular, humor, and communities ought to be recorded. But do we have—do we need—a James Eads How?

Author’s Note: All imagery and quotations from Hobo News issues were made possible by the St. Louis Public Library, which has digitized 40 issues from the magazine’s first five years of operation.

Marc Blanc is a Ph.D. candidate in American literature at Washington University in St. Louis. His research traces an interracial history of leftist publishing in the Midwest during its boom years, 1877–1945.