While scientifically correct, few West Virginians call them crayfish. Unless you’ve got a PhD, calling them crayfish around here marks you as someone out of place.

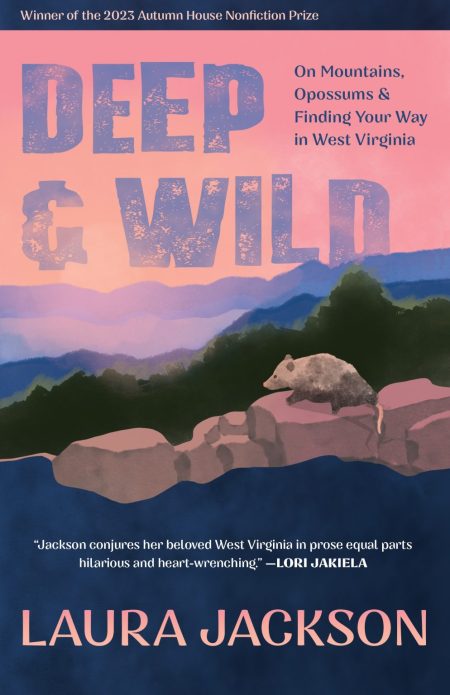

By Laura Jackson

The following is an excerpt from Deep and Wild: On Mountains, Opossums, and Finding Your Way in West Virginia by Laura Jackson and released by Autumn House Press.

Ben lifted the smooth, flat rock and plunged his hand into the shallows of the Greenbrier River. Water shot out from beneath his palm and the river bottom clouded over as he stirred up silt.

The current swirled around our crouching bodies. Often, when my kids pulled out a crawdad, it was attached to their finger, their pink flesh gone white in its vise.

“It pinches but not really but kind of a little bit but just stop being a weenie, Mom,” Ben said. I didn’t want to. I was a weenie. I’d never caught anything more than river dust, and the craw knew it. They took advantage of my hesitation, every time.

To catch a craw, my sons told me, you really need to commit. They hide under flat rocks, but it’s rarely a simple lift-and-catch. When the rock comes up, a billowing cloud of sediment obscures the riverbed and your intended target, and in that moment, they bolt. Craw escape by propelling themselves backward, tails tucked, at astonishing speed. Experienced craw hunters may have a net ready, especially if they can anticipate which direction the animal is going to go, but this is difficult when the silt clouds your view. It takes dexterity and practice.

Crawdad, or crayfish, eat whatever they can find on the river bottom, including dead and decaying plant and animal matter. We have roughly thirty species in West Virginia, both aquatic and burrowing. While some have been extirpated, notable species include the endangered Guyan- dotte River crayfish (found in only two Wyoming County streams), the Greenbrier Cave crayfish, and a newly discovered, bright blue, burrow- ing species, the Blue Teays Mudbug. Several species and their habitats are federally protected due to dwindling numbers, a result of habitat destruction, often from coal mining operations.

While scientifically correct, few West Virginians call them crayfish. Unless you’ve got a PhD, calling them crayfish around here marks you as someone out of place. It’s like saying New Or-leens, rather than the way my grandparents, born and raised in the Big Easy, always said it: “New Aw-linz.” Drop crayfish into riverside conversation amidst anglers and, immediately, you’re an outsider. Expect your license plate to be examined.

“Did they say ‘crayfish’? Damn Virginians. I bet they got Perrier in that cooler, too.”

I’ve got a degree in environmental studies, but I’m a native West Virginian, and I don’t want to be an outsider in my home state. Most Appalachians call them crawfish or crawdad. (I know this because I took a very scientific social media poll of my friends—some from northern Appalachia, some from southern Appalachia, and a few Flo- ridians who just wanted to add their twenty-five cents.) But I’ve never liked either term, as the animal is neither a fish nor a dad. A sperm donor, yes, but the male crawdad aren’t out there coaching their spawn through a T-ball game. And forget crawdaddy. I’m not uttering anything that makes me sound like a backwoods porn star. Some folks use the term mudbugs, which is too close to bedbugs for me. So, I’ve settled on saying craw. Everyone here knows what I’m talking about when I say craw, and nobody feels the need to check my cooler or my academic credentials. And I’m not the only one who favors craw. In my tackle box, I have a lure by the Rebel company shaped like a crayfish. It’s called the Wee Craw. They make a bigger version called the Big Craw and a smaller one called the Teeny Wee Craw. Alternatively, if you need a deep diving lure, you can go with the Deep Wee or the Deep Teeny Wee Craw. And if you’re feeling especially finite, whip out your Micro Craw. After all, it’s not the size of the craw that matters—it’s how you dangle it in the water.

Nevertheless, live bait has the advantage of realistic movement and delectable smell. Despite the craw’s propensity for mischief, no other bait so tempts a smallmouth bass, which is why the craw hunt contin- ues. The search may be the most entertaining part of a day on the river because there’s another crayfish characteristic that becomes glaringly apparent when you do catch one. As you hold the tiny creature up to your face, its legs flail and stretch outward to appear more threatening. Its antennae swirl around, trying to make sense of its position in space. This is an animal on the defense, but only for a second, because the most notable quality of the craw is its supremely shitty attitude. They’re the chihuahuas of the rocks, the Napoleons of the river. The craw is the ultimate curmudgeon. It raises its claws and swipes at your face. Come at me! I’ve never seen an animal so tiny yet so determined to kick my ass. The craw doesn’t care how small it is or how big you are—it wants to take you down. Craw defense is craw offense.

Of course, holding a shrimpy brawler high in the air while it takes a swing at you with an I’ll-kill-you-you-gangly-motherfucker glint in its eye only makes us laugh, which probably incenses it even further. And I had to sympathize with a craw that Ben’s brother, Andy, caught on the Greenbrier River that day. Minding its own business one moment and the next, plucked from its home, held aloft, and mocked by giants.

“Look at that guy,” I said to Andy. “He wants to murder us.” The critter swung its claws ferociously, and in that moment, I was certain I was looking not at a set of pinchers but at a tiny middle finger held aloft in my face. Screw you, lady! Screw all of you! We gave the contentious crustacean to my husband, who hooked it through the tail and cast it downstream. It must have been an unforgivable insult. Craw are swift and grumpy and funny-looking, but they hold onto their dignity. As it flew through the air, legs rigid and outstretched, I could almost feel its rage.

Though bass love craw, there’s a downside to using them as bait: the animal is obnoxious when hooked. It’s a lot like tying your dog to a chair. She wanders in circles, weaves around your legs and the chair’s legs and, within twelve seconds, is hopelessly tangled. Then, she just stands there, immobilized and utterly confused as to how it happened. And you try to untangle her and get frustrated and ask her why she does this every single time and how hard is it to just lie down and freaking stay there, dog? That’s like fishing with a live craw. You can see your line moving as they crawl under rocks, over rocks, around and through logs. You may be tempted to set the hook, thinking a fish has taken a bite. Nope. It’s that wretched craw, wandering around the river bot- tom. It happened to my husband, who reeled in to find the little twerp had doubled back and was crawling toward him along the fishing line like a tightrope walker. Behind the craw, several feet of braided line twisted and wrapped around itself. By the time he untangled the knots, he was frustrated. He recast both line and craw, claws again extended in fury, downriver toward a deep hole. When the animal hit bottom, it apparently decided it had had enough: it removed the hook from its tail and sauntered off, no doubt in a huff.

Not every craw-catcher is scouring the river for bait, though. There are plenty of folks who eat them. My friend Christina grew up in Mar- shall County, West Virginia, a rural place. She told me about a swanky political fundraiser she attended on Long Island. The hall was deco- rated in the swag of schmoozing, and the event’s visual centerpiece was a canoe filled with boiled crayfish. She found herself staring at the crim- son pile of claws and legs. No doubt, memories of her childhood rushed in—hot July days, “crick” shoes sliding along smooth rocks slick with brown algae, mayflies rising, sunburns and shouts and the heavy smell of humidity trapped beneath the summer canopy.

“Aren’t you going to have a crayfish?” someone asked her. Christina looked at the boat, piled high with the familiar lobster-

lings. The presentation was meant to feel exotic, a rare and adventur- ous delicacy brought in from afar.

She squinted and shook her head.

“Where I come from,” she said, “we call that bait.”

Christina’s event is called a craw boil. The tradition belongs to Lou- isiana, where crawfish are regularly eaten, and the culmination is the presentation of craw not on a plate or in a chafing dish but in a towering heap. After boiling them, you chuck them on the table in a steaming mound, sprinkle on your seasoning of choice, toss in a few ears of corn and, perhaps, a mix of andouille sausage, garlic cloves, or whatever pleases your palate. Boil-goers pluck craw from the pile.

A mess of craw is just that—a mess. They need to be cleaned of mud before they can be cooked, and you can buy an eighty-dollar craw- fish washer if you’re so inclined. It functions like a jetted tub: a hose attaches to the base of the bucket and the water shoots out at an angle, creating a current that stirs the craw and scrubs the mud off. After ten or fifteen minutes, when the water runs clear, the craw are ready for another sort of hot tub.

This is where I get uncomfortable because, until this step, the stars of the craw boil are usually very much alive.

I watched a YouTube video on how to boil craw and spent most of it dreading the moment when ten pounds of live crustaceans would go into the seething, orange stew. The hosts of the video, enthusiastic bar- beque chefs, spoke of the craw as though they were potatoes or carrots. The animals crawled all over each other in a mesh bag that twitched with their movements. When the time came, the hosts made a Jacuzzi joke and dropped them in, as one would a donut into a fryer.

I’m not sure how to justify my discomfort. It’s incredibly hypocritical of me to sit here feeling upset about the boiling of crustaceans when I had a pulled pork sandwich for dinner last night. Nobody wants animals to suffer, but it’s much easier to push this conflict away when your din- ner arrives having already shuffled off its mortal coil.

“Well, it’s already dead here on my plate. Can’t let it go to waste. Ethical dilemmas are more of a lunch discussion anyway. Oh, there’s bacon, too? Shit, pass it over.” Maybe these feelings boil down to the moment you meet your dinner for the first time. Dead dinner, enjoyable. Live dinner, disturbing. And watching that bag of craw shimmy on You- Tube disturbed me.

I’m not the only one. In 2003, David Foster Wallace visited the annual Maine Lobster Festival for Gourmet Magazine and came away unsettled about the nature of the festival and the consumption of the crustaceans in general. While festivalgoers are tying on their plastic bibs and lining up to partake in the celebration, he wrote, the lobsters in the mess tent are huddled in their temporary tanks, looking stressed, and when they go into the pot, it looks like a painful death.

It must take a certain constitution to be the boiler, to stand there all day, listening to them clang desperately on the pot lid. To paraphrase Wallace, lobsters really hate being boiled alive. And maybe these sea- food festivals are unique, because I can’t think of a whole lot of other American events where the main course is slaughtered while folks are standing in line to eat it. We like our food dead. We don’t want blood on our hands. And I have to wonder if the Maine Lobster Festival would be as popular if you had to boil your own lobster. Pluck him from his tank, stare him down, chuck him in, and listen to that screaming sound they make, even if it is just steam escaping the animal’s carapace.

I’ve never eaten a craw. I’d like to know what they taste like, sort of. Craw can’t bang on the pot’s lid, but I don’t have the stomach to plunk a mass of them into a pot of boiling water for the sake of a crayfish essay. Admittedly, at the end of the how-to video on YouTube, when the barbeque chefs dumped the scarlet, steaming mudbugs out onto a cutting board, they looked like they smelled pretty good. But it was a twice-removed sensory experience, so don’t base your next backyard gathering on what I’ve written, here.

“Time to eat these guys,” one of the YouTube chefs said. He picked up a craw, broke it in two, placed the upper half of the animal’s body against his lips, and sucked audibly.

“All the juice is in the head,” he said. The other guy did the same thing and made a slurping noise as his cheeks pulled in with the force of his suck.

At this point in my research, Ben looked over my shoulder. “Is he sucking that craw’s brains out?” he asked.

The chefs demonstrated how to break the exoskeleton and eat the tail meat. But by then, they’d lost me. The brain-suck was enough to turn me off. And, like Christina said, it still looked like the contents of an upended tackle box, anyway.

The craw in a craw boil are Procambarus clarkii, the Louisi- ana crawfish. According to the West Virginia Reddit community, our endemic species taste like mud, though it doesn’t stop locals from con- sidering a feast now and then.

“Where can you buy live crawfish for a crawfish boil?” someone asked on a regional thread, hoping for a hookup with a seafood shack or fishmonger.

“They’re free in the creek,” came the reply.

We never once thought about tasting the Greenbrier River craw the kids caught. I may abhor the name “mudbugs,” but that’s what they look like. It’s easy to see how the craw wash is such an important step in the boiling process. Still, even if our craw looked clean and delectable, I’m not sure I’m ready to suck anything’s freshly cooked brains out. I’m not even brave enough to grab one out from under a rock.

By the end of our weekend on the Greenbrier River, I still hadn’t caught a craw. The kids had a difficult time disguising their pity for their poor mom. She fell a lot, they noted, and wasn’t fast enough. Also, she was clearly afraid of being pinched, an anxiety that compounded when Ben found and suffered the wrath of a hellgrammite, the larval stage of a horrifying creature known as a dobsonfly. If you’re unfamiliar with that insect, imagine an earwig had a threesome with a dragonfly and a rhinoceros beetle. Larvae look like a Jurassic throwback: dark bod- ies, spindly legs, and piercing mandibles that rival the craw’s claws in size. The difference between a hellgrammite and a craw is that the craw pinches you to teach you some respect; the hellgrammite does it just to be a dick.

After one too many hesitations when I should have been bold and stuck my hand under a rock, my family eased up on their expectations. It was obvious to them I wasn’t getting the hang of the hunt. And though they didn’t say it, I knew I was the outsider. To be fair, I’d helped to catch several. I was good at spotting which way the craw darted when the boys lifted the rocks, so they made me The Official Craw Spotter, but I was pretty sure it was the kind of consolation job you give the loser of the group, the one who has poor hand-eye coordination and little chance of success on her own. Still, I’d rather be pitied than pinched, a thing I have yet to experience. It seems like an unavoidable part of this river- side ritual and a necessary step in the education of a competent craw- catcher, and I know, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that I am indeed being a weenie. I guess I don’t want the craw badly enough. Maybe craw-hunt- ing isn’t for everybody, regardless of where they’re born. Maybe, when all is said and done, I’m grabbing at something I’m not meant to catch.

Laura Jackson is an environmental writer and humorist. A lifelong West Virginian, she holds an MFA from Chatham University in Pittsburgh. Her work has appeared in many places, including Terrain, Brevity, Hippocampus, Still, and Bayou Magazine, and she writes regularly for Wonderful West Virginia and West Virginia Living magazines. Laura’s essay, “The Imperfect Aquarist” was listed as notable in Best American Essays 2021. She lives in Wheeling, WV, where she rescues homeless animals and spends time with her sons on mountains and in rivers.